There is increasing evidence that Latin America’s recent entente with China is deepening the region’s dependence on commodities. But closer economic ties with India could have the opposite effect—and at a crucial moment, as the region recovers from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain crises.

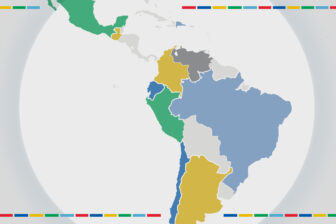

Latin America’s long-term reliance on commodity exports hasn’t changed as the region develops more ties to China. Commodities still make up more than half of total exports in 15 out of 19 countries in the region. Excluding Mexico, the only major outlier, 73% of Latin America’s exports consisted solely of commodities in 2020. A recent article in the UN ECLAC Review states that trade with China has brought about a “return to the commodity export model and a reduction in industrial activity in the Latin American countries analyzed, particularly in the high-tech sectors.” A reduction in manufacturing activity and, consequently, manufacturing jobs, would spell disaster for the region’s post-COVID economic recovery.

In this context, India may provide just the right opportunity for Latin America, at the right time. According to data compiled by this author for a report published by the Wilson Center, India has an edge over China in value-added sectors in Latin America, specifically in manufacturing, healthcare, information technology (IT) and services. Although the size and scale of Indian investment in Latin America is still relatively smaller—on the order of $12–16 billion, compared to $159 billion from China—in comparison with other international investors, its impact is felt through employment generation and the diversification of the economy to value-added sectors, particularly in services.

India-Latin America trade has also increased from just $2 billion at the beginning of the 21st century to a peak of nearly $50 billion in 2014, remaining near that level before falling to $30 billion in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. India is among Latin America’s top five largest export destinations. But much of the region’s exports to India are currently commodities, including crude petroleum oil, minerals like copper and gold, and vegetable oil. Still, given India’s propensity to consume large quantities of consumer goods, the region should be looking at India as a future market for its value-added products, particularly food and agricultural products, machinery, and fast-moving consumer goods.

India’s IT companies employ more than 38,000 people in Latin America, a number that seems to multiply every couple of years. A single Indian automobile parts company, the Samvardhana Motherson Group, has 27 manufacturing plants in Latin America that employ 25,000 people—more than all the employment generated by Chinese automobile companies in the region. India has also exported more pharmaceutical drugs to Latin America than China has throughout the 21st century. And more importantly, 27 Indian pharmaceutical companies have invested in the region and operate 13 manufacturing units. Not only does this increase local production (particularly generic drugs that treat cancer and HIV/AIDS) but the presence of India’s low-cost, high-quality drugs also helps reduce the cost of public healthcare in Latin America.

China’s presence in Latin America has justifiably received much attention in the US, but little is known about India–Latin America relations. Four key differences separate India’s and China’s presence in Latin America.

First, while China has a proactive Latin America policy outlined through white papers and supported by political visits, India’s relationship with the region is driven by the private sector and economic diplomacy, while politics and ideology remain secondary. Second, China’s massive investments in Latin America are strongly backed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including through political visits that make newspaper headlines. In contrast, Indian investment nearly always emanates from the private sector, staying well under the radar of most Latin America observers.

Third, India’s investments in Latin America are in the region’s value-added sectors, including in pharmaceuticals, IT, automobiles and manufacturing, in contrast to China’s investments that tend to skew towards extractive industries and infrastructure. As a result, Indian investment creates far more jobs on average; according to a Colombian study that tracked investments between 2005 and 2015, “for every million dollars invested in Colombia, India created 24.6 jobs, while Asia Pacific created 3.5 and the world 2.7.” The broad motives behind Indian investment in Latin America are market expansion and diversification (to enter markets less regulated than the West, but with more purchasing power than other regions like Africa and South East Asia) and also to join regional value chains. Although many Indian companies, specifically in the IT sector, first entered the region due to its proximity to the US market, today their motives are to court local or regional clients in Latin America.

Finally, in contrast to China’s one-party rule, India is a democracy, like much of Latin America (with a few exceptions). India’s socio-political structure has far more in common with Latin America than China does, with similar challenges like multi-party coalitions, social unrest and protests, and political corruption.

Over the past decade, Latin America has begun paying far more attention to India, owing partly to India’s rapid economic growth in the 21st century, its increasing salience in global value chains as well as the large and growing middle class consumer market that has often made India the region’s largest export market after the US and China. Both parties have generated more goodwill that has led to an increase in political visits. The recent visits by India’s deputy foreign minister Meenakshi Lekhi to Panama, Honduras and Chile are emblematic of India’s rather low-key, cordial relationship with the region. In Honduras, Lekhi visited an IT center set up by India and inaugurated an irrigation project funded by a line of credit from India. In Panama, she addressed the 15,000-strong Indian diaspora (along with a Panamanian minister of Indian origin). And in Chile, she met with members of Parliament and addressed a business gathering at SOFOFA, the country’s premier business association.

The previous month also saw the visit of Argentina’s foreign minister, Santiago Cafiero, to India on April 25-27. Besides his usual meetings with Indian politicians and businesspeople, he also sought New Delhi’s support for an international commission that would strengthen Argentina’s claim on the Malvinas Islands.

So, where are India–Latin America ties headed in the post-COVID world?

The answer more likely lies in the hands of the private sector, diplomatic missions and trade promotion agencies, individuals and organizations on both sides than on politicians in New Delhi, Brasilia, Mexico City or Buenos Aires. The future of India–Latin America relations can be aptly summarized by Antonio Machado’s poem: “Caminante, no hay camino, se hace camino al andar (Traveler, there is no path, you make the path as you go).”

—

Seshasayee is an advisor to the Government of Colombia and a non-resident fellow of the Woodrow Wilson Center. This article incorporates data and findings from a recently published Wilson Center report, “Latin America’s Tryst with the Other Asian Giant, India.”