SÃO PAULO – After a few days of business meetings in São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, the international visitor may be forgiven for thinking the winner of next year’s presidential election could well be someone other than President Jair Bolsonaro or former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. After all, a growing roster of seemingly affable, center-right politicians are projecting themselves as contenders, promising to steer clear of the turbulent rivalry between Bolsonaro and Lula and his Workers’ Party.

The buzz for a “third way” candidate is big – at least in Brazil’s urban centers. Even on Faria Lima Avenue, the heart of Brazil’s financial center in São Paulo, bankers who once supported Bolsonaro are now dreaming of an alternative to the president, who has embraced full-blown economic populism.

Just look at the increasingly bitter struggle between João Doria, the governor of São Paulo, and Eduardo Leite, the governor of Rio Grande do Sul, for the nomination of the center-right PSDB. Ample media coverage would suggest both have a real shot in 2022. Analysts are also discussing whether former star judge Sergio Moro and Senate president Rodrigo Pacheco will throw their hat into the ring.

The victory of one of these men, the story goes, would put an end to the destructive polarization that has riven Brazilian politics and help the country heal after an abysmal decade of near-zero growth and worsening inequality. Third way proponents frequently mention last year’s municipal elections, when old-school center-right parties triumphed – evidence, many assumed, that Brazilians had grown tired of polarization.

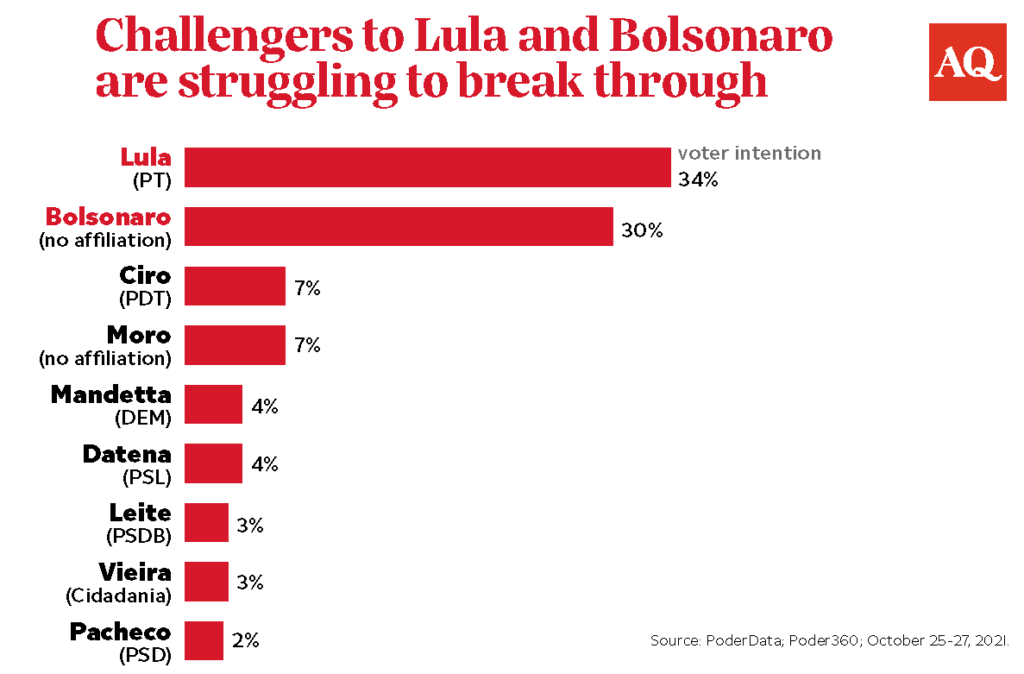

Yet all of these third way candidates share a glaring problem: They perform dismally in polls. Two recent Poder360 polls of voter intentions show no third way candidate surpassing 8% of the vote, with Lula and Bolsonaro leading comfortably in the double digits. In a separate Poder360 poll, 36% of respondents say they would only vote for Lula, while 28% would only vote for Bolsonaro.

While much could change before the first-round election on October 7, 2022, there are five reasons why a truly competitive third-way candidacy is currently unlikely.

For starters, most voters are simply fine voting for either Lula or Bolsonaro, even if many public opinion makers and a growing number of elites express the desire for an alternative. According to Poder360, only 12% of the electorate says they are unwilling to vote for either the president or ex-president. Further, several third-way candidates face low name recognition outside of their respective home states – a serious problem in a continental country of around 150 million voters.

More importantly, it would be a mistake to believe that this group is, in any way, cohesive. The opposite is true: Some former Bolsonaro voters who are disappointed by the president’s failure to combat corruption, for example, now plan to support Moro, Leite or Doria. Their commitment to the third way, however, goes only so far, and if the center-left Ciro Gomes became the third option, many would reluctantly support Bolsonaro again. The same is true for Gomes’ supporters, who likely would rather vote for Lula than for any third-party candidate right of the center.

The fact that a growing number of politicians are considering entering the race – eleven, by a recent count – suggests that none of the candidates in the third-party tent seem to be able to consolidate support within the diverse group of voters who dislike both Lula and Bolsonaro. And even if it is possible to whittle a crowded field down to one candidate, mutual attacks within the group will bruise egos, making it unlikely that the eventual third-way option receives genuine support from the rest.

The second challenge for a third-way candidate is that both Lula and Bolsonaro have a strong incentive to run against the other, suggesting that the leading third-party candidate may end up being attacked from both sides. While Lula’s spot in the run-off is all but certain, his worst scenario would be a faltering Bolsonaro campaign and the rise of a competitive center-right candidate capable of attracting centrist voters. For Bolsonaro, too, his main rival, for now, is not the Workers’ Party, but the center-right PSDB. He is likely to focus on discrediting whichever third-way candidate has a chance to make it into the run-off.

Third, even though Bolsonaro is currently struggling, it would be highly unusual for an incumbent president in Brazil to miss out on a runoff. Despite his erratic stewardship of the economy and his catastrophic mishandling of the pandemic, Bolsonaro retains a highly committed followership that, radicalized by the president’s sophisticated communication strategy, is unlikely to abandon the president even if Brazil’s economy deteriorates further. More importantly, Bolsonaro can direct public spending strategically, and his recent decision to support the reinstitution of cash-transfer programs until his election can be expected to boost his approval ratings. As was the case with Dilma ahead of the 2014 elections, presidents can hide economic crises for some time and create the illusion of stability – for example, by increasing highly unsustainable energy subsidies – until election day. With Bolsonaro’s relationship to the financial markets in tatters, he may be even freer to embrace his populist self.

Fourth, every single one of the politicians vying to lead a united anti-Bolsonaro-anti-Lula front suffers from shortcomings that are bound to limit their broader appeal. Ciro Gomes, the third-place candidate in 2018, is seen as abrasive, and his recent attacks against the Workers’ Party sound increasingly desperate. Moro, the former judge, lacks political acumen and remains a single-issue candidate at a time when the fight against corruption is no longer a priority for voters. Doria scored a big political victory in early 2021 when he inaugurated the vaccination campaign in Brazil, while the president embraced denialism. His track record on human rights is equally noteworthy, with police in São Paulo now killing fewer people than before. And yet, Doria’s low likeability score and his decision to opportunistically ride the pro-Bolsonaro wave in 2018, when he ran for governor, weigh like an albatross on his neck. Of all the third-party candidates, Leite, the 36-year-old governor who recently came out as gay, may have the best chances, but his support for Bolsonaro in 2018 makes him unpalatable even to center-left voters who dislike Lula. More worryingly, he remains unknown to many Brazilians merely a year ahead of the election, and several bigwigs of his party are unlikely to fall in line if he wins its nomination.

Finally, the narrative that there is a path for a centrist candidate between a right-wing populist and a left-wing populist is likely to be weakened by Lula’s move towards the center. Indeed, given Bolsonaro’s populist economic measures, it is no longer fanciful to consider that markets may actually prefer Lula over Bolsonaro in 2022, expecting the former president to again embrace economic orthodoxy over the highly interventionist approach of Rousseff, his handpicked successor. Add this to Lula’s active courting of conservative evangelical voters, his likely decision to pick a moderate – or even conservative – figure as his vice president and a centrist as economy minister, and it may be hard for the chosen third-party candidate to argue that he is the only centrist option in the race.

Having said that, the adverse scenario for a third-party candidate may still change if Brazil enters a spiral of economic collapse and rising inflation in the coming months. Such a scenario could threaten Bolsonaro’s place in the run-off, opening a space for the center. For now, however, expectations that a third-party candidate will make it are mostly wishful thinking.