Correction appended below.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.” This popular epigram, attributed to the 19th-century French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, succinctly describes the evolution of Venezuelan economic policy over the past three years. Since 2019, the government’s decisions to relax economic restrictions have prompted dollarization in the economy and a few signs of a rebound. But these changes are limited, and they only benefit a small fraction of the country — according to a new study, 76.6% of Venezuelans live on less than $1.20 a day.

Venezuela continues to suffer one of deepest economic depressions in the history of the Western Hemisphere. Between 2014 and 2020, the economy shrank by a staggering four-fifths. But as it shrank, especially since early 2019, so did the capacity of the Venezuelan state to intervene in it. Now, the government still makes and remakes the rules as it likes, but there is new space for private actors to participate in sectors where government presence has been reduced, such as manufacturing and imports of goods and services.

Over the last three years, imperfect substitutes have filled gaps in the provision of services in a handful of areas. One stopgap is the black market, now projected to encompass some 20% of Venezuelan GDP. Another is the semi-legal “grey” market, which encompasses swaths of the commercial sector, imports, construction, real estate services and rentals.

These new, improvised areas of dynamism in the Venezuelan economy are thanks in part to several decisions made by Nicolás Maduro’s government. In late 2018 and early 2019, price controls and restrictions on currency exchange were relaxed, and the official exchange rate for the bolívar was lowered to match that set by the market. On October 1, the government renamed the national currency the “digital bolívar” and trimmed six zeros from amounts denominated in the currency up to this point.

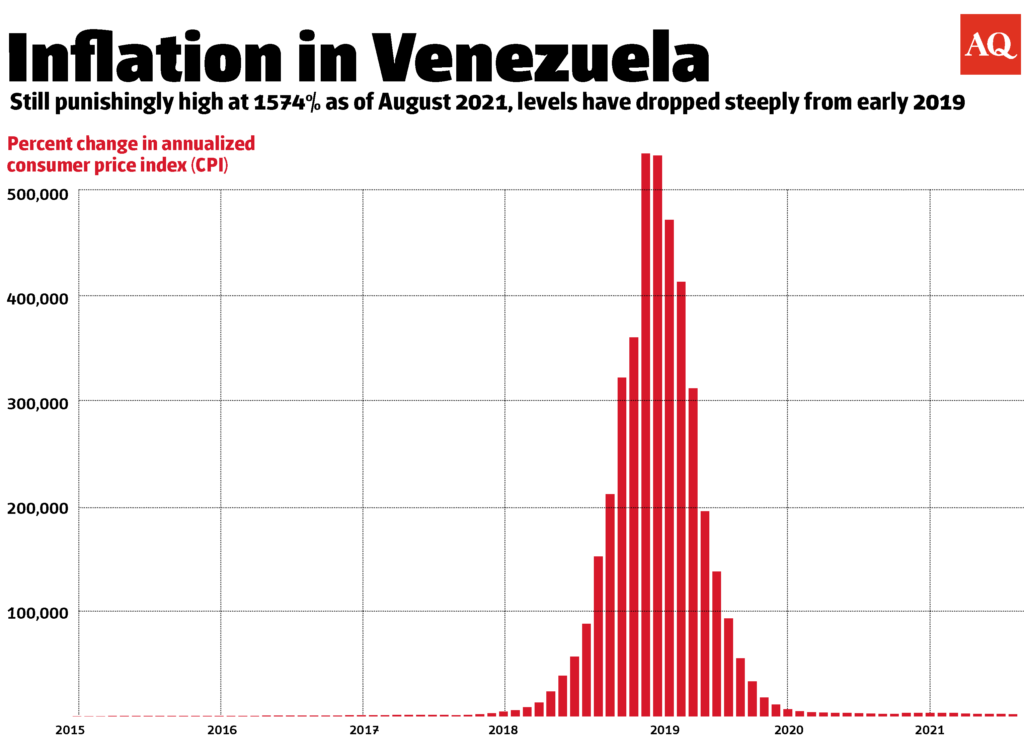

Another striking change came with the government’s decision to allow the widespread use of foreign currencies in domestic transactions. As recently as 2018, Maduro called dollarization “unconstitutional” — but by late 2019, hyperinflation had forced him to adopt a more flexible, if inconsistent, stance on the matter. Publicly, he changed his tune, saying he “did not see [dollarization] to be a bad thing.” Since then inflation, though still high, has dropped, while dollarization has given the informal economy a boost in metropolitan areas.

In recent years, the government has also allowed the private sector to participate in areas formerly overseen by state enterprise. With an “anti-blockade law” promulgated in October 2020, the government formalized an established practice of tacitly allowing cooperation with the private sector inside state-owned companies, and extended the practice to economic areas over which the state previously reserved exclusivity, such as hotels, food production, and energy. To keep the market supplied as domestic production of goods has collapsed, the government has relied heavily on imports for decades — and most importation is now carried out by the private sector, buoyed by the opening of new ports, for example in Puerto Cabello, La Guaira and Maracaibo.

But all these changes must be considered in perspective. The government’s actions do not amount to a stabilization program, nor to structural reforms capable of restoring the economy’s path towards growth. There has been no substantial shift in the way economic policy is conceived or executed. The government’s reduced scope of action is merely an ad-hoc adaptation to adverse conditions. Productive capital has plummeted, financial capital is scarce, and human capital has suffered losses due to migration. Sanctions limit the government’s ability to distribute favors to interest groups whose continued goodwill is essential for its political stability.

Along with decreased state intervention in the economy, there has been a significant reduction in public services. The government is concentrating its remaining resources in politically prioritized metropolitan areas while, abandoned by the state, the rest of the country is forced to look to the private sector or other local actors for electricity, fuel, public transportation, and water.

The Maduro government’s primary goal is to stay in power. Any sign of “pragmatism” in the government derives from an instinct to preserve the regime. With this goal in mind, giving a shattered economy a small breather is worth even a break with some of the government’s oldest ideological precepts. Likewise, if Venezuela’s economy has stabilized, it has done so at the bottom of a deep depression. Economic dynamism is concentrated in just a handful of specific niches that promise to grow in the coming years – for example, healthcare, retail, and technology. In such an environment, the private sector has slightly more bargaining power than before. But the current economic opening is not nearly enough to produce results along the lines of the Chinese model of materially prosperous authoritarianism.

In Venezuelan society today, families must navigate a punishing wave of poverty on their own, without state support. Many citizens are excluded from the few remaining economic activities that can offer formal jobs or decent wages, while humanitarian concerns continue to plague the country. The government’s economic “adjustments” can do little to reverse this situation, and Venezuela remains small, unproductive, and poor.

A previous version of this article misstated the size of the contraction in the Venezuelan economy from 2014 to 2020

—

Oliveros is the director of and partner at Ecoanalítica, a Caracas-based economic and financial consulting firm