LIMA, Peru — Peruvians have long referred to the imposing neoclassical seat of their country’s Supreme Court and other key tribunals in downtown Lima as the “Palace of Injustice.”

Surprise verdicts that fly in the face of overwhelming evidence, prosecutors allowing serious human rights and corruption cases to run out their statute of limitations, and strong cases shelved on an attorney’s opaque whim have too often seemed the norm.

But now, thanks to a potentially momentous referendum on institutional reform, the entrenched graft infecting Peru’s legal system might just be under threat as never before.

President Martín Vizcarra, who took office in March after his predecessor Pedro Pablo Kucszynski resigned amid conflict of interest allegations, is pushing Congress to approve a referendum on four anti-corruption measures before the end of the year. The proposal includes a change in the way judges and prosecutors are appointed, and comes in response to the latest mega-scandal to hit the judiciary here.

Beginning in July, a series of wiretaps carried out by Peru’s Constellation anti-narcotics surveillance program and leaked to the press has revealed conversations between judges, corrupt middlemen and suspected criminals that point to widespread tampering with the criminal justice system.

Allegations of judicial corruption are hardly a surprise in Peru, but what appears to have lit the bonfire of public fury is the very banality of the conversations. In the first of those recordings, Supreme Court Judge César Hinostroza can be heard apparently negotiating a bribe from a convicted child molester. At one point he asks if the victim, thought to be 11 years old, was “deflowered” before then inquiring whether the perpetrator wanted his guilty verdict overturned or simply his sentence reduced.

Since then, new audios have even implicated ONPE, the electoral agency, and Popular Force, the scandal-prone hard right party of Keiko Fujimori – currently the subject of a high-profile money laundering investigation – that dominates Congress. In one of the conversations Hinostroza is heard accepting a meeting with a “Mrs. K.”

Nevertheless, the president’s decisive response in calling for the referendum has come as a surprise to many observers. Vizcarra had been widely seen as an honest but accidental chief executive lacking the will to stand up to a hostile legislature.

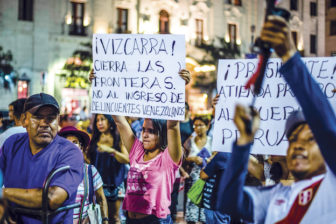

But with anti-corruption protests sweeping the country in a way unseen here since the fall of former President Alberto Fujimori in 2000, Vizcarra is pressuring Congress to approve the referendum by December at the latest. All eyes are now on Fujimori to see whether she will buckle and let Popular Force lawmakers vote for reforms that could weaken her behind-the-scenes grip on power — and expose her to criminal prosecution.

The stakes are equally high for the country, with many observers viewing the referendum as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address the endemic graft that has corroded faith in democratic institutions.

Even before the latest wave of tapes, Congress and the judiciary were viewed, according to Transparency International, as easily the country’s two most corrupt institutions. Meanwhile, under Fujimori’s tight control, Congress has seen its approval rating fall to 12 percent, according to one poll.

Vizcarra’s proposal is in some ways similar to a recent inititive in Colombia, in which legislators and activists managed to trigger a referendum on a series of measures to tighten up governance. Peru’s president has proposed four questions for the referendum, including a new formula to choose representatives for the National Council of Magistrates (CNM), which hires and fires judges and prosecutors, and was disbanded after its members were caught up in the audio scandal. The other measures, targeted at political corruption, are the prohibition of congressional re-election; strict regulation of party finances; and the re-establishment of the Senate to balance out Peru’s current 130-member single legislative chamber.

There is now vigorous debate in Peru about the merits of those proposals. The ban on lawmakers running to retain their seats is wildly popular, but has been slated by most experts for potentially making Congress even more inefficient. “It’s a little absurd,” said Paula Muñoz, a political scientist at Lima’s University of the Pacific, noting that the rate of congressional re-election in Peru is already relatively low at less than 30 percent. “It has little to do with corruption. It’s not as though members of Congress rob more during their second terms.”

Yet two proposals that could have a real long-term impact are the measures to reformulate the CNM and – finally – put some teeth into the legal framework that ostensibly regulates the veritable Wild West of political fundraising in Peru.

The former could eventually radically reduce the number of crooked judges and prosecutors while the latter would block the narco-money and capital from organized crime that, most experts agree, has penetrated Congress. “At the moment parties are not even required to publish their accounts during the campaign,” Muñoz told AQ. “There is no serious enforcement. Transgressors get fines, which they often get away without paying.”

After more than two years of throwing its weight around in Congress, where it has a majority despite only receiving 36 percent of the popular vote, Popular Force has now been backed into a corner by Vizcarra’s harnessing of public rage over graft. After narrowly losing the last two presidential elections, Fujimori has seen her once rock-solid approval rating decline over the last six months from around 35 percent to just 10 percent in one recent poll.

No longer able to rely on cover from the courts, her biggest problem is not “winning the next election, but rather not going to jail,” notes Augosto Alvarez Rodrich, a prominent Peruvian journalist. Fujimori is now suggesting her party will block the referendum in Congress, describing it as “populist” and saying that it “does not correspond to the country’s needs.”

A best case scenario, said Muñoz, might be that the CNM and party finance proposals are approved in the plebiscite. The worst case scenario would be that Popular Force defies both Vizcarra and much of the Peruvian electorate and derails the referendum entirely. That would leave a weakened president at the mercy of a hostile congressional majority that, critics say, routinely acts in ill faith.

It would also cause even further damage to Peruvians’ already vanishingly slim trust in their democratic institutions. “The chips are in the air,” said Muñoz. “No one knows how they will fall.”

—

Tegel is an independent journalist based in Lima, Peru