Scandals and corruption investigations unfolding in Latin America have given development banks a terrible reputation: They stand accused of feeding crony capitalism, transferring resources from taxpayers to undeserving billionaires, and making lending decisions that misallocate capital at the whims of bureaucratic planners who do not necessarily know best.

Should we just close them, implode their buildings and salt the land where they stand? We’d argue for a more moderate route: Development banks can create value to society, as long as they tackle market failures, fall within the budgetary process and have good governance structures.

Let’s start by examining the conditions under which development banks are useful, and then look at what institutional improvements are needed to ensure they are not misused in Latin America.

First, development banks serve a function no other institutions are willing or able to serve. Poor countries often lack well-functioning financial markets. Commercial banks shy away from funding long-term and infrastructure projects or only do so at prohibitive costs. International financial institutions fill some of these gaps, but their development lending priorities may differ from national ones. They are also not granular enough and fail to reach smaller projects that may have great potential.

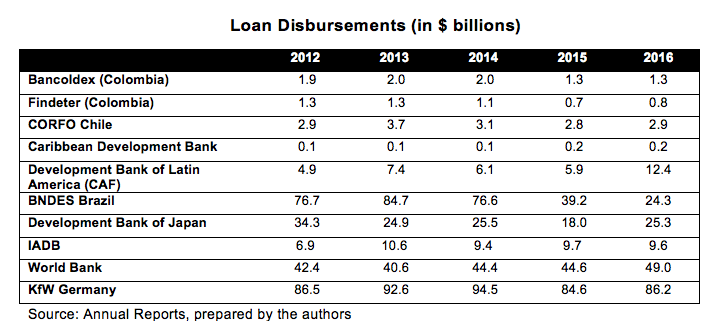

Wherever there are good projects that would fail without financing, there is a role for development banks. In the past, rich countries made use of such institutions as well. In the U.S., the first development bank was the War Finance Corporation, created in 1918 to give financial support to industries related to the war effort, and to provide funds for commercial banks that aided such industries. Today, the largest national development bank in the world is the German Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau (KfW), with Chinese banks growing quickly.

Historically, development banks played an important role in Latin America. They featured prominently in the quest for industrialization, with a mission of allocating financial resources to selected industries, for better or for worse. They thrived in Brazil, Colombia – host to four specialized institutions – Chile, Mexico and other countries in the region. Beside those national development banks, there are also three important multilateral development banks in Latin America, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and the Caribbean Development Bank.

But how can we avoid the pitfalls of development banks?

Let’s use the case of Brazil, where these flaws were clearly exposed by the recent corruption scandals involving directed credit allocation. Critics have argued that the practices of BNDES, the largest development bank in Brazil and one of the biggest in the world, facilitated the action of corrupt politicians, even if its staff have so far remained clean.

Indeed, BNDES was the instrument for an indefensible strategy to create “national champions” that would compete globally. That was accomplished by transferring public resources to large, politically connected conglomerates that never say no to a politician’s request for campaign finance or backpacks full of cash. A single company, JBS, had access to cheap funds to the tune of almost $4 billion between 2002 and 2013 to play in the global merger game. Heads we win, tails the taxpayer loses. As one would expect, the national champions policy only boosted oligopolies, misallocated capital and transferred wealth to the rich. BNDES served as a textbook example of what to avoid, but there are also useful lessons to be drawn from the bank’s flawed empire building over the last 10 years.

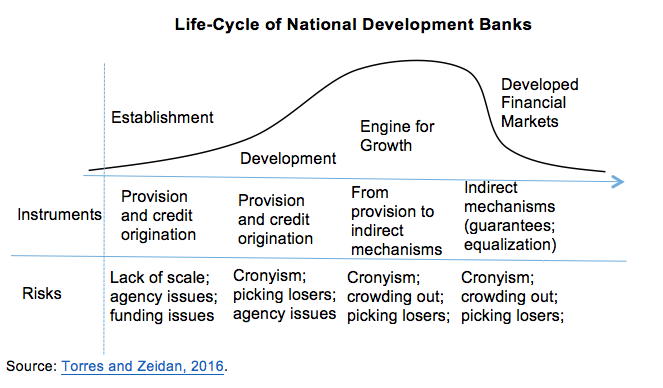

Ideally, development banks, especially national ones, should follow a life-cycle, playing specific roles that shift over time, according to a country’s needs and level of development. In the earlier stages, the most important function is the creation of long-term credit. Later, as financial markets develop, development banks should become purveyors of indirect credit mechanisms, such as guarantees to exporters and other subsidies to facilitate long-term projects. Finally, as countries escape the middle-income trap or financial markets become truly robust, these institutions may be winded down or focus in specialized niches, such as student loans, agriculture subsidies or other markets in which market failures are a recurrent phenomena.

Finally, governance matters. Development banks should have clear mandates, transparent rules, and open accounts so society can monitor their investment choices. Subsidized lending ought to be brought into the budgetary process: If governments cannot decide on a whim how much to spend on schools, why should they have free rein to allocate scarce resources to corporations? Moreover, the operations of development banks ought to fall within the perimeter of national bank supervisors and be constrained by the best international practice in bank regulation, so as to avoid excessive risk-taking and limit losses. They should also focus on long-term projects and small and medium enterprises, as they tend to have much lower access to credit than large conglomerates.

Development does not come from throwing cheap money around to see what sticks. Moreover, these banks can be useful, within a circumscribed role. But it takes good governance to make a development bank work for the people. Are Latin American countries up to the task?

—

Zeidan is a business and finance professor at New York University in Shanghai and Fundação Dom Cabral, and E.C. Filho is an economist.