Information technology is shaped by the organization that uses it. It is also shaped by the practices of the people who use it in their work. New kinds of information technology, or ways of processing work-related information, are thought to make work routines more efficient. In police work—just as in the work of doctors, lawyers and engineers—there is a persistent wish to cut through the complexity and get to the “heart of the problem” with a practical solution.

I would call it the “silver bullet fantasy.” The arguments for police body cameras fall into that category.

Police officers are pragmatic. They seek the simplest, quickest and most effective technology to perform their jobs. At the same time, they value their freedom from close supervision and are wary of “big brother.” These basic elements of law enforcement culture suggest we should be skeptical about whether the introduction of body-worn cameras will effectively address the concerns many critics have had—especially since the deaths of unarmed civilians in Ferguson, Missouri, Staten Island, New York, and elsewhere—about the lack of police accountability.

A historical perspective puts this in context. Since the late nineteenth century, politicians and police supervisors have sought to apply information technology (IT) to their work in order to improve response times and increase transparency. Consider, for example, the call box, the radio, the two-way radio, the computer-based dispatch, and the now widespread use of social media by police departments to inform citizens of their activities. More recently, cameras have been placed in patrol cars and closed-circuit technology video devices have been installed in more public spaces.

But often, IT is more about the efficient management of information systems than about enhancing the quality of police work. By tradition and legal precedent, policing is a secret and protected craft. In many respects, judges and prosecutors are quite happy not to know what “processes” ensued prior to any matter brought to their attention.

Let’s be clear. Observational research of police officers interacting with citizens reveals that force beyond kicking, punching and pushing is not frequent.1 But the nature of the job makes unexpected violent episodes likely. Police are protected, sanctioned and even rewarded by having these uses of force—including lethal force—overlooked by law and tradition.2 Can we expect these uncertain, unexpected responses to be reduced or altered simply by being recorded? The technologies of any occupation are modified by the occupational culture, and the premise that a technology always reconfigures work in the expected way is false.

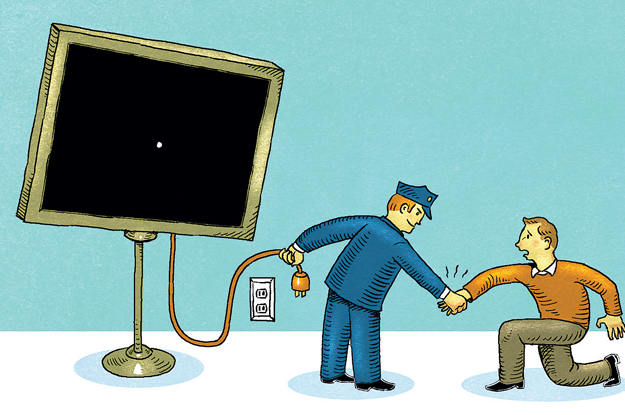

It should surprise no one that when cameras or other devices are used to monitor patrol officers, they have responded by turning off cameras and microphones, by “forgetting” to turn them on or to insert fresh tapes, by changing the camera angle, and by deleting strips of images. Officers have also failed to replace tapes and have taped over previous recordings by reusing tapes. Departments amplify these practices by failing to properly supervise the processing of data. Even if there are rules about keeping cameras and microphones on, supervising officers may not regularly view and monitor the tapes, check officers’ use of them, maintain records of taping, or sanction officers who do not follow policies and procedures.3

These actions are forms of resistance to new IT, and they are rooted in the occupational culture of patrol officers. Any new surveillance technology is viewed with ambivalence. Although it could be argued that recordings of the officers’ words and actions protect the officer in internal investigations, civil suits or criminal charges, they could also reveal the everyday brutalities and incivilities that research has shown are routinely employed in policing in this country.4

It has been proposed that miniature cameras worn on the uniform will increase accountability. This claim has no empirical basis. There has been little systematic research on the question. Police typically announce the success of innovations before they are evaluated. The police position generally is, “Why would we do it if we did not think it would improve things?” So, this begs the question: What would accountability-based body cameras mean?

There are two kinds of accountability: an in-advance definition of what is expected, and an after-the-fact justification for the decisions made. In policing, organizational accountability of either kind is an empty illusion because law enforcement is a profoundly conservative, stable and ossified institution. It has survived the community policing movement with little or no change in training, deployment, rewards systems, or management. The closest thing to true organizational accountability might be when the federal government places a department under a consent order for a specific pattern of abuses—for example, the Consent Decree Regarding the New Orleans Police Department in 2012.5 But even with such oversight, the same structure, supervision, training, rules, regulations, and protective mandate—the tacit agreement between society and the police that gives police latitude to define how best to do their jobs—remain unchanged.6

Consider why holding individual officers accountable in any case is problematic. The organizational structure gives officers significant discretion on patrol, and leaves them unsupervised with respect to when, how, why, and to what end they intervene in an incident. They are required after the fact to justify their actions—if they were known to the organization. But many actions are not recorded, or are labeled “action taken.” The tacit assumption within the police hierarchy is that you cannot easily judge individual decisions because “you had to be there” to understand.

This ideology makes investigations, and holding individual officers accountable, very difficult in practice.

Let us assume that there are few, if any, changes in the police organization except for the introduction of body cameras. If cameras are used, one might ask about the processing, use and management of the incredible number of hours of data that would be generated. How will they view, code, store, analyze, and apply these data? If you trust the police, you trust their words and deeds—it’s a contract.

The hope is that body cameras or statements by commissioners or chiefs regarding changes in policy will transform practices. But there is little evidence that top-down management policies or local and state legal rulings change police practices. Since supervision, training, rewards, and practices have not changed, what evidence is there to suggest that a camera on an officer’s lapel will change behavior?

Read Shira A. Scheindlin’s argument here.