This June, the Organization of American States (OAS) revoked a 1962 resolution that expelled the Cuban government on the grounds of its political and military links to the former Soviet Union. Many supporters of revocation argued the decision was overdue: after all the Soviet Union no longer exists, and the OAS had long since outgrown one of the key roles envisioned for it in 1948 as an instrument of Washington’s Cold War strategy.

But this was not about fixing a diplomatic anachronism. It came about as a result of a battle waged by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and his unsavory allies—Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, Bolivia’s Evo Morales and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa—aimed at awarding a moral and political victory to the Cuban government and a proportional defeat to “Yankee imperialism.”

The Cuban leadership appeared not to care about the debate, claiming that whatever the outcome, they weren’t interested in returning to that “rotten whorehouse or ministry of colonies” called the OAS. The statement only underscored the fact that the campaign led by Chávez was not based on concern for changing Cuba’s status as part of a constructive effort to augment continental solidarity. It was nothing but artillery fired at Washington with the objective of humiliating the new administration.

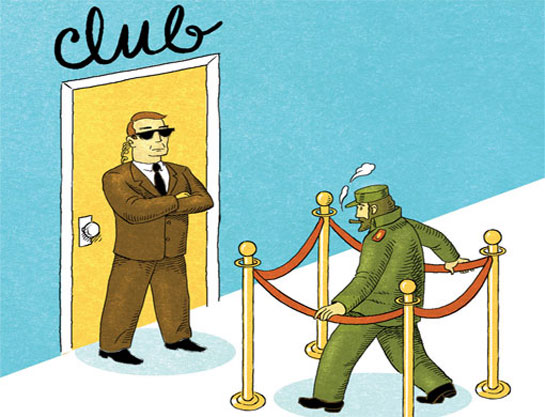

Why did President Barack Obama’s government lend itself to a move conceived to damage the U.S.’s image and interests? One theory is that the OAS is no longer what it once was and that its purpose now is to strengthen the democratic governments using the Inter-American Democratic Charter signed on September 11, 2001, in Lima, Peru. For that reason, Washington agreed to revoke the resolution but explained that such action did not automatically open the doors of the OAS to Cuba, because the island had to submit to the spirit and letter of the Democratic Charter.

In Havana, Caracas and the other twenty-first-century capitals of socialism around the hemisphere, officials celebrated the new defeat inflicted on “the Empire.” But, to maintain moral consistency and defend American interests, the Obama administration should have pushed instead to replace the 1962 resolution with a resolution affirming that Cuban membership in the OAS was conditional on its acceptance of the spirit and letter of the Charter.

That would have satisfied the need to put an end to a formal anachronism, without succumbing to Chávez’ bullying and provocation. Of course, that would have obligated U.S. diplomacy to wage a hard battle against Chavismo—a task that does not seem to elicit the slightest enthusiasm in the State Department.

Therein lies the heart of the matter. Seen from the American perspective, Chávez and his accomplices are seemingly insignificant, low-intensity enemies with whom the U.S. trades intensely (10 percent of U.S. crude oil imports come from Venezuela). The most convenient way to treat them, therefore, is to avoid them—the way one avoids a drunken and oafish neighbor.

Is this perspective reasonable? While Chávez may be more interesting from an anthropological than a political standpoint, it isn’t obvious that he is more of a “nuisance” than a “danger.”

The fact is, Chávez and Chavismo are a danger to U.S. security in at least two fundamental aspects: by turning Venezuela into a haven for the transit of cocaine into the U.S. as the U.S. General Accounting Office acknowledged in a July 2009 report, and into a circuit of political coordination for other sworn enemies of the U.S. such as Iran and North Korea.

It is true that a power as great and powerful as the United States has little to fear from the actions of Chavismo, but the prudent approach is to at least understand what its enemies do and why they do it. Chávez and Fidel Castro came to the conclusion early this century that Venezuela and Cuba had been given the difficult but honorable task of fighting against Yankee imperialism and capitalism, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The aggressive behavior of the Soviet Union after World War II led to U.S. diplomat George Kennan’s famous recommendation of containment, which shaped U.S. Cold War strategy for most of the latter half of the twentieth century. It is time that something similar be done to counter this new anti-Western outbreak.

However, it should no longer be a battle between Washington and the Caracas-Havana axis but one between those nations that respect individual rights and true democracy (like the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Peru, Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia) and those that tend toward authoritarianism. This new group of democracies must then design a strategy to defend against the authoritarian-leaning populist backlash seen in parts of the region.

Low-intensity enemies are enemies just the same. Taking them seriously is an inescapable act of common sense.