When Louis Michel, then-development commissioner for the European Union (EU), met in 2009 with Bruno Rodríguez, Cuba’s foreign minister, he worried openly about the slow pace of EU diplomacy. “I think that if the European Union does not consolidate the normalization of relations with Cuba,” Michel said, “the Americans will do so before us.”1

He need not have been concerned.

In the nearly five years since Michel and Rodríguez sat down together, the Cuban government has pursued reforms to pry the island’s economy back from the edge of crisis—ranging from creating space for entrepreneurship to ending travel restrictions.

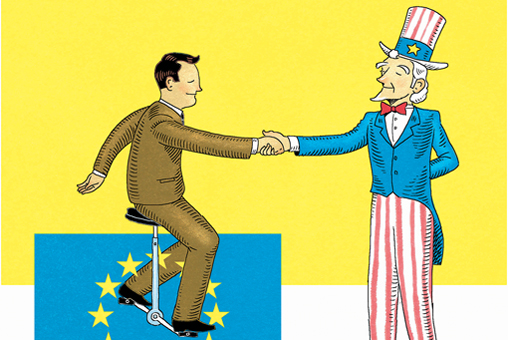

Now is the time for the United States to follow its Atlantic partner and get off the sidelines when it comes to engaging Havana. The Obama administration’s track record signals some hope: thus far, the president has used his executive authority to restore Cuban-American family travel, reinstate people-to-people trips, and reconvene the episodic talks on migration and postal delivery. But he has left undisturbed the essential architecture of U.S. policy inherited from the Eisenhower era.

Beyond the 52-year-old embargo, the clear obstacle to engagement is the Helms-Burton Act, enacted by Congress in 1996 to block any diplomatic opening to Cuba unless a future administration exacts existential concessions from a transitional Cuban government succeeding the Castros. But the EU has also been hamstrung by its Common Position—which was adopted the very same year and might be described as “Helms-Burton Lite”—yet they have worked around it.

The EU concluded that the Common Position failed to achieve its purpose, and that neither American toughness nor European flexibility does the Cuban people or its member countries much good. It also concluded that Raúl Castro’s leadership has changed in some fundamental ways the circumstances in which Cuban citizens live and work—so much so that Europe’s top negotiator, Christian Leffler, says the reforms triggered the talks.2

For its part, Cuba was eager to come to the table. As one European source told Reuters, “Cuba wants capital, and the European Union wants influence.”3 Soon afterward, the first formal meeting between EU diplomats and their Cuban counterparts produced a roadmap for the negotiations, and the process was underway.4

It’s time the U.S. admits that our far harsher sanctions on Cuba have also failed. Unfortunately, the weight of history and habit have thus far prevented the administration from building on the sensible but incremental reforms President Obama already offered, and is allowing the EU to go first in direct negotiations. What will get him to move now?

Not economics. While Cuba would undoubtedly benefit from expanding trade relations with the U.S., U.S. corporations have demonstrated very little appetite for the Cuban market or its 11 million consumers. Even after the success of Tom Donahue’s visit to Cuba in May with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the private sector is likely to wait for normalization to occur rather than advocate that it happen faster, given the Obama administration’s aggressive enforcement of the embargo.

Nor will politics carry the day. Despite winning the Sunshine State in 2008 and 2012, and polls conducted this year that show majorities in South Florida and Miami-Dade County supporting normalization, there is no indication the White House will move boldly after treating the diaspora community politically like a Fabergé egg for years. Even if it waits until after the 2014 elections, there are three powerful arguments that can and should persuade the administration to follow Europe’s lead and engage in direct negotiations with Cuba’s government.

First, negotiating would help the U.S. repair its role in the region. Every nation—from the powerhouses of Brazil and Mexico to the conservative capitals in Colombia and Canada—has embassies and trading partnerships with Cuba, except the United States. By insisting on policies that isolate Cuba, we’ve created conflict inside the Organization of American States and given impetus to the creation of new regional institutions like the Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States—CELAC) that embrace Europe but exclude us.

Second, negotiating will align us with the economic and political interests of Cuba’s people. President Castro’s economic opening, while incomplete, is also real.5 It is offering Cubans more choices, jobs and pay, and greater control over their own lives.

Third, negotiating can put the issue of freeing usaid contractor Alan Gross and broader questions like human rights on the table. The European Union made it clear that its concerns about democracy and human rights in Cuba will still influence its policy, and the Cuban government made its acceptance of that fact clear. As Carlos Alzugaray, Cuba’s former ambassador to the EU, recently observed, Cuba’s government abandoned its demand that Europe repeal the Common Position before it would start negotiations. As the Associated Press reported, Cuban officials have said “they are prepared to discuss any and all issues on a basis of mutual respect.”

If the U.S. is prepared to drop its preconditions requiring Cuba to meet U.S. political requirements before we sit down to talk, we can engage with Cuba’s government, respecting its sovereignty and building its confidence, so we can turn the conversation to the sensitive political subjects that U.S. sanctions over the course of 50 years have never persuaded the Cubans to discuss.

A decade ago, the Bush administration never would have followed Europe’s lead. Under its Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba, Caleb McCarry, the transition coordinator, worked hard to apply political pressure on our democratic allies in Brussels so they would converge behind the much harder-line regime change policies that originated in Washington.

At the time, then-senator and presidential candidate Obama called it “naïve” to continue a U.S. policy that had failed for decades. Now that the failures of the Common Position and Helms-Burton have converged, President Obama has a great opportunity to stand by his words, follow Europe’s lead, sit down with Cuba, and negotiate a new relationship that will realize our country’s national interest while also helping Cubans realize a better future for themselves.