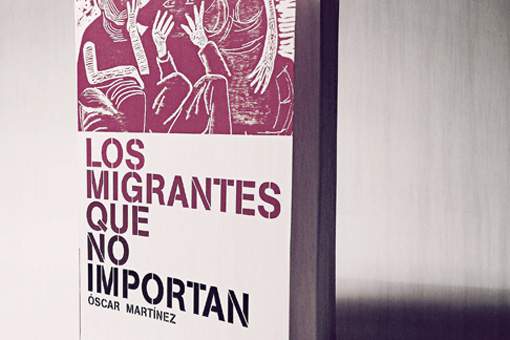

In Los migrantes que no importan (The Migrants that Don’t Matter), Óscar Martínez depicts a dark side of Mexico that few people know. The book, based on stories published in El Faro—an El Salvadoran digital newspaper whose founder is interviewed on page 53 of AQ—describes the hardships experienced by thousands of undocumented Central American migrants as they make their way through Mexico toward the United States.

Divided into 14 chapters—each covering different dimensions of the 3,000-mile journey in which migrants board trains, sleep in shelters and struggle to find the money to keep going—is a poignant portrait of the men and women who are driven by economic misfortune and political insecurity to leave their home. “Their countries spit out what they don’t want, and these people are the spittle,” a would-be migrant told Martínez.

Martínez, a 30-year-old freelance journalist, spent more than a year following the migrants north through Mexico—joined by a small crew of photographers and filmmakers. The journey benefited from the advice and cooperation of advocacy groups along the way. “You have to consider the social reality of our countries if you’re going to understand anything,” Luis Flores, the coordinator of the Tapachula office of the International Organization for Migration, told Martínez.

The book’s key revelation, which may surprise many U.S. readers, is that few of the migrants ever reach their ultimate destination. Along the way, many are forced by tragedy or by lack of money to give up their dreams of a better life in the “north.”

One important focus of Martinez’ chronicles is the tragedy of women migrants. Many end up as low-paid domestic workers and others become victims of sexual violence. According to a 2010 report released by Amnesty International, six out of 10 female Central American migrants suffer sexual abuse while crossing Mexico. For many women, their journeys end in dive bars or brothels in border cities and towns in southern Mexico, where local authorities turn a blind eye. “I went to Huitxla once to work and was stopped by the migration police,” said Connie, a Guatemalan woman whose real name is not revealed by Martínez. “The head of migration made it clear that if I had sex with him, he’d let me go,” she said.

Another prominent setting in many stories is the “great iron snake,” a legendary train also known as La Bestia (The Beast). According to Martínez—who rode the train on eight occasions—The Beast is the “route par excellence of the undocumented Central American migrant.” The book reveals the mutilations, robberies, kidnappings, and murders that take place in the train’s empty cars.

The author also visited migrant shelters along The Beast’s tracks to highlight another aspect of their struggle to survive: the efforts of individuals and organizations who take in the migrants, providing shelter, food, rest, and legal defense. I am proud to count myself among this group, as director of Sin Fronteras.

The book also documents the abuse that migrants face at the hands of organized crime. These groups are neither isolated nor small. Their success stems from their ties to corrupt authorities and businesses in the communities where they operate.

Even for the migrants who make it to the northern border with the U.S., the hardships continue. These rugged, thinly populated areas are dominated by drug traffickers who force migrants to carry drugs in exchange for help crossing the border as so-called burreros. Their only alternative is to spend whatever savings they have left to hire rapacious polleros or coyotes to guide them across the desert.

These unsavory activities—and the tragedies—along the northern border are well known. But the book‘s revelations about what happens to migrants in Mexico itself add a new, chilling dimension to the story. The impunity for crimes against migrants is a grim subset of the general impunity in Mexico for human rights abuses.

Los migrantes que no importan should add additional weight to demands in Mexico for greater accountability and transparency in its justice system. But it should also call much-needed attention to a group of individuals who, for reasons beyond their control, have become victims of the political and economic tragedies suffered by the entire region.