This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on how to make Latin American cities better. Click here to see the rest of our Top 5.| Leer en español

BUENOS AIRES – For decades, living here was an exercise in extreme nostalgia.

The Belle Epoque of the 1920s and 1930s, when Buenos Aires was one of the world’s richest cities, had long since given way to collapsing buildings, shattered sidewalks and abandoned parks. During the economic collapse of the early 2000s, armies of recyclers sifted through trash and parts of the city flooded constantly. Once, visiting a flea market, I saw a group of residents begin to cry while leafing through black-and-white photos of the city’s glory days. “Look what we’ve lost!” one exclaimed.

Today, the economy is in crisis once again. But Buenos Aires is enjoying a renaissance nonetheless, and has arguably reclaimed its mantle as the most livable major city in Latin America, thanks in part to its peripatetic mayor, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta. Despite limited financial resources, the 52-year-old Harvard Business School graduate has orchestrated big investments in infrastructure, expanded a new, highly trained police force, and is painstakingly bringing city services to long-neglected areas like Villa 31, Buenos Aires’ largest shantytown.

In doing so, Rodríguez Larreta has accomplished the seemingly impossible: You can now find porteños who believe their city’s best days are ahead of it. “I have to admit, I don’t remember the city ever looking better,” said Maria Carmen Binotti, 83, a regular at the city’s iconic La Biela café. “Those guys have done a pretty good job.”

Rodríguez Larreta visits an anti-bullying program.

Rodríguez Larreta visits an anti-bullying program.

How did this happen? “I think the key is good management,” Rodríguez Larreta told AQ. “The city was very poorly run, and the truth is that we generated a lot of savings with austerity so we could use that money for investment.” Buenos Aires has controlled the growth of current expenditures, and now dedicates 35 percent of its budget to investment, up from 20 percent in 2014 and a modern city record. “That’s why you see the city broken everywhere,” he said, referring to construction sites. “We’ve put much more emphasis on public projects.”

That approach was born from necessity. From 2007 to 2015, the city received practically zero federal funding for investments because of a political dispute between Mauricio Macri and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who were then the mayor and president, respectively. During that period, Rodríguez Larreta was Macri’s chief of staff, running much of the city government’s day-to-day business. Yet even since their success catapulted Macri to the presidency in 2015, money has remained tight. The recent recession, and ensuing plunge in tax revenues, has forced the city to keep relying on multilateral lenders like the Inter-American Development Bank — or on creative, relatively low-cost initiatives.

More: How Better Connecting the Suburbs Could Fuel Growth

The city’s efforts to incentivize bicycle use is an example of the latter. Instead of merely painting lines on streets (as New York City usually does), Buenos Aires has created more than 140 miles of dedicated bicycle-only lanes and also a free, city-run bicycle-sharing program. “Why is it free? Because the benefit to the city of a person who puts aside their car for a bicycle is several times larger than the cost,” Rodríguez Larreta explained. “It’s the best investment we could make.” Since 2009, bicycle use has expanded seven-fold, and now accounts for more than 3 percent of overall trips.

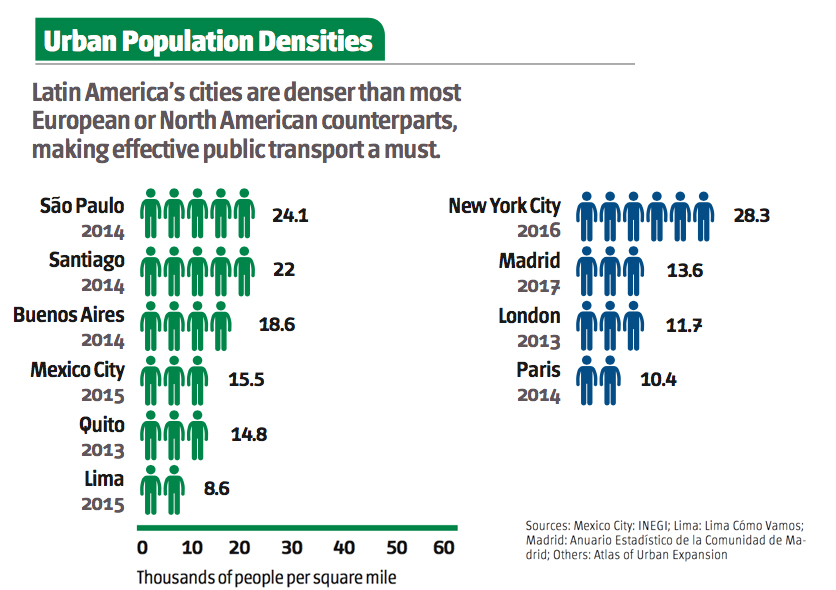

That’s still a small number. But the overwhelming number of city residents who use public transport or cars have also benefited. The Metrobus project, which opened dedicated bus lanes on Buenos Aires’ most iconic avenue (and was based on similar initiatives in Bogotá and Curitiba, Brazil), was a triumph not just of civil engineering but also cultural change in a city notorious for its skepticism of new construction. Investments in new subway trains have allowed for a 50 percent increase in riders in the last two and a half years, to 1.5 million rides per day. The mayor’s “city on a human scale” program has emphasized pedestrians over cars, and shut down automobile traffic in broad swathes of the city center.

The result is a city where — outside of construction zones, anyway — traffic flows better than before and residents feel healthier. That’s a recipe for attracting and building a skilled labor force, and it’s no accident that Buenos Aires has Latin America’s most high-profile cluster of technology companies and is home to four of the region’s six “unicorns” — privately held start-ups with an estimated value over $1 billion. At a time when mayors around the region are struggling to prepare for changing job markets amid increasing automation, Rodríguez Larreta has a plan in place. Public school students have access to tablet computers from kindergarten onward. Based on input from the city’s software companies, recent high school graduates also have access to vocational training to prepare them for possible programming jobs.

“This city is betting on human capital, and on the creative industry in particular,” the mayor said.

Some critics argue that such initiatives are too flashy, and Rodríguez Larreta has not focused enough on the city’s working class. Sergio Abrevaya, an opposition legislator, says he has not done nearly enough to improve access to low-cost housing, for example. “The city is becoming too expensive for too many people,” he complained. Rodríguez Larreta counters that there is still plenty of space to build, and gentrification won’t be a real problem in Buenos Aires “for another 30 to 50 years.” He has also addressed polls that show crime is city residents’ number-one concern by shifting more police out of administrative jobs and providing a salary bonus of 8 to 10 percent for officers who are on the street.

Indeed, Rodríguez Larreta’s core operating principle is being on the street himself. “I have one of the prettiest offices in the city, but you’ll never find me there,” the mayor said with a smile. We met at La Biela, and were interrupted several times by residents lodging complaints or offering other feedback. “If we had lots of resources, I suppose it would be easier,” Rodríguez Larreta said. “But I love being out here. This is where the action is.