SÃO PAULO – When mass protests forced Ecuador’s President Lenín Moreno to reverse course on a cut to fuel subsidies last month, most Brazilian political risk analysts interpreted the crisis as a country-specific event. An outbreak of protests in Bolivia the following week was similarly seen in Brazil as a largely isolated incident. Despite other recent protests in Peru, Honduras and Haiti, few observers in Latin America’s largest economy believed such events would have broader implications for the region.

That changed when protests in Chile, initially in response to a hike to subway fares in Santiago, led to a social conflagration of a size and intensity unseen since the country’s return to democracy three decades ago. When President Sebastián Piñera, suddenly fighting for political survival, put his pro-business agenda on hold, replacing his minister of finance and increasing the minimum wage and pensions, Brazilian analysts started scrambling to assess whether something bigger might be afoot – and whether protests could spread to Brazil and cause the government of President Jair Bolsonaro to rethink one of the region’s few remaining unabashedly neoliberal agendas.

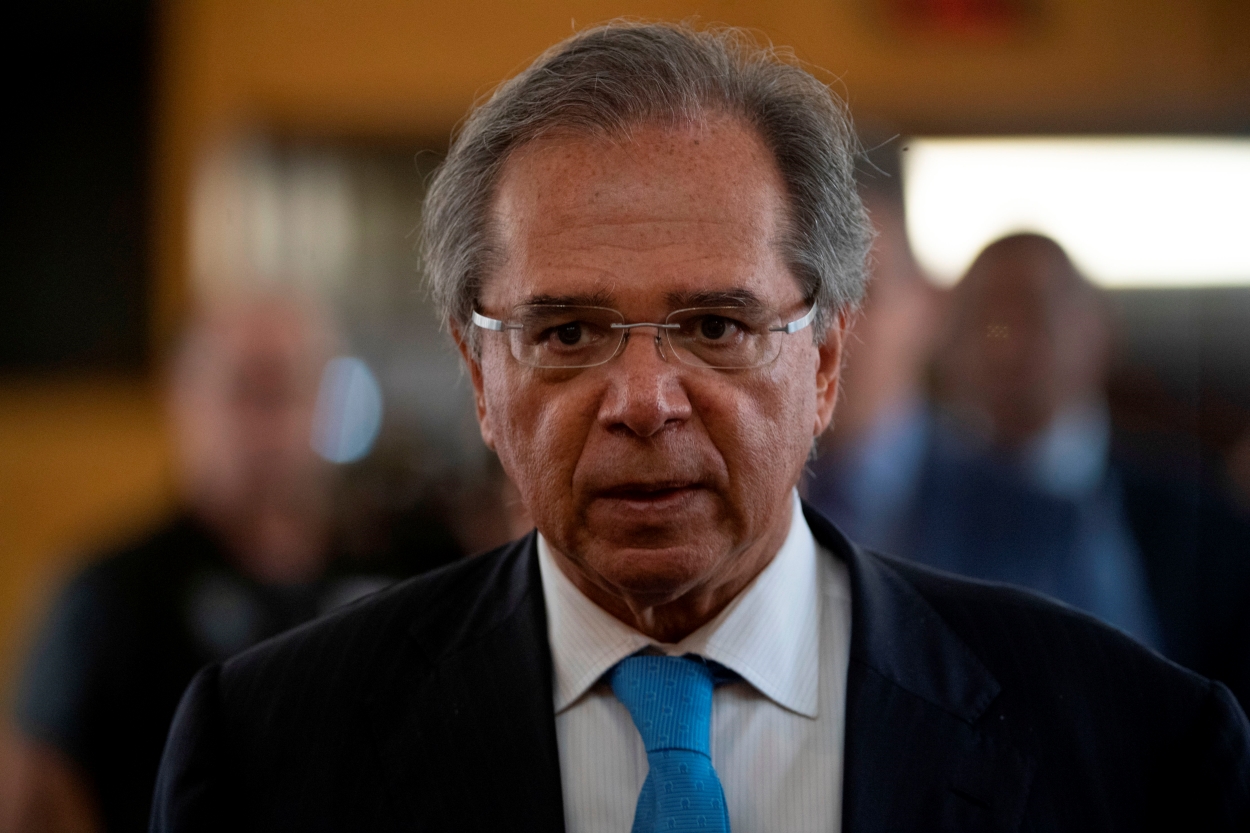

Prior to recent events, the vast majority of Brazilian investors, supportive of economic reforms led by Finance Minister Paulo Guedes, considered Chile to be a model to follow. Guedes, who holds a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and worked in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship, often refers to Chile’s economy as an inspiration. Thus Chileans’ mass mobilization against inequality and insufficient public services has raised uncomfortable questions about the political feasibility of Guedes’ reform proposals. As an economist at a Brazilian hedge fund recently told me, “If it happens in Chile, it can happen anywhere, right?”

The recent outbreak of protests in Colombia has not helped to quell such concerns. Political instability across Latin America has strengthened those in the Bolsonaro administration who want to delay the announcement of Guedes’ additional reform projects, fearing they could trigger a public backlash similar to those seen elsewhere. Led by Bolsonaro’s chief of staff Onyx Lorenzoni, this more cautious group recently won an internal battle against Guedes, who had hoped to present a series of new proposals before the end of the year, including rules that would affect sensitive issues like job security in the public sector.

Given these fears – and uncertainty over the possible public reaction to proposed reforms – Guedes is unlikely to be able to push through his plans at the speed he initially envisaged. Predicting the likelihood and timing of mass protests is hard; Brazilian elites where taken by surprise when an increase in metro fares in 2013 triggered the largest protests in decades. In the same way, virtually nobody in Chile foresaw the explosion of public unrest in 2019, even though former President Michelle Bachelet warned as early as 2014 that more needed to be done to combat inequality and avoid political instability – a view many regarded as alarmist at the time.

In defending a more assertive approach to reform, Guedes is likely to point out several reasons why it would be simplistic to expect recent unrest elsewhere in the region to spread to Brazil. First, public debate in Brazil is far less connected to the region than it is in other countries. The average Brazilian does not follow political events in Latin America and is thus unlikely to be inspired by protests in Chile or Bogotá. Second, Brazil saw protests of historic dimensions only six years ago, when millions vented their anger and frustration and indirectly caused the collapse of the country’s political party landscape. That, in turn, led to the election of a populist president who embraces an anti-elite discourse, making a classic anti-establishment protest, such as the one seen in Chile, less likely. Considering how rare such seismic shifts have been in Brazilian history, a second wave of mass protests in less than a decade strikes many observers as improbable.

Those favoring a more cautious approach, however, could point out that Brazil fares worse than its neighbors in several key economic dimensions that have contributed to recent protests – including inequality, unemployment, and economic growth. The economies of Chile, Bolivia and Colombia have all outperformed Brazil over the past few years, and Brazil is South America’s most unequal country. Unemployment remains stubbornly high, and the number of Brazilians living in extreme poverty has recently risen to 13.5 million. In addition, given Bolsonaro’s penchant for demonizing his opponents and limited interest in genuine dialogue, his capacity to defuse tensions after initial protests would probably be low. Belligerent rhetoric and a heavy-handed approach involving the armed forces to suppress protesters could cause small demonstrations to swell quickly.

In the end, price increases on bus and train fares can be delayed, but not put off indefinitely. Unavoidable fare hikes in major Brazilian cities in 2020 will give government officials sleepless nights, and provide a litmus test to the likelihood of broader social unrest in Brazil. The same is true for price increases on diesel fuel, which could revive protests by truck drivers that forced former President Michel Temer to undo price hikes in 2018. Policymakers will likely try to announce price adjustments during the long summer vacations from December to February, when university students have a harder time getting organized.

There is one final aspect which may explain why protests are likely to continue surging across the region: demonstrators have succeeded in extracting meaningful concessions from leaders who are overwhelmed by their size and determination. Whether in Ecuador, where protesters achieved the reinstatement of subsidies, in Chile, where protesters succeeded beyond expectations and forced Piñera to call for a constituent assembly, or in Bolivia, where anti-Morales protesters ousted the president, Latin American leaders have been remarkably vulnerable to large-scale protests this year.

The protesters’ key strength may lie in their leaderless format, which makes it nearly impossible for governments to negotiate with representatives and then lull them into largely symbolic compromises. This may explain why most protest movements do not allow opposition leaders to speak on their behalf – even though some, such as Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, have tried – and why ex-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s recent release from prison is unlikely to affect chances of mass protest spreading to Brazil.

As long as protests in other Latin American countries succeed and produce tangible benefits, the risk of them spreading to other countries, including Brazil, remains relatively high.