In the Buenos Aires everyone knows, the Buenos Aires of opera houses and bifes de chorizo and nightclubs that don’t dream of opening until 1 a.m., you can almost forget there’s a recession going on.

The steakhouses are full, the rose gardens are in bloom, and grand avenues hum with the city’s iconic black and yellow taxis. On late spring evenings, you can sit at a sidewalk cafe and sip an Old Fashioned while the aroma of lime-tree flowers wafts through the air and professionals in yoga clothes hurry by. Not all is well here — nearly 2,000 stores closed in 2016, crime is a problem, and the city’s unemployment rate has ticked up to nearly 10 percent. Yet some sectors, particularly technology, tourism and finance, are prospering. And even the surliest porteño will grudgingly admit the city looks better and is run more efficiently than it has been in 20 years — perhaps much longer.

This is a remarkable feat: The Buenos Aires I knew, when I lived here from 2000 to 2004, was an abject disaster. Grand old mansions were abandoned to squatters. Cafes sat empty. Thousands of jobless cartoneros picked through garbage at night searching for recyclables or scraps of food, often with their small children perched precariously on wooden wagons alongside piles of cardboard and sheet metal. This was the period Argentines still refer to darkly as la crisis — a historic implosion that saw gross domestic product (GDP) shrink 20 percent and a third of the workforce become jobless, generating so much popular rage that in 2001 there were five presidents in a span of two weeks.

Buenos Aires’s recovery didn’t really begin until 2007, when Mauricio Macri, formerly the head of Boca Juniors, a soccer team beloved by the city’s working class, became its mayor. Macri set about pragmatically healing the wounds of la crisis and modernizing a city notoriously obsessed with the lost glory of its belle époque a century prior. New bicycle and bus lanes were built. Trash and graffiti were removed. School nutrition programs and “health stations” in parks appeared. Macri was so successful that, despite a patrician manner even his fans describe as somewhat aloof — he is a master of the upper-class Argentine art of tying one’s sweater casually around one’s neck— he was elected president in October 2015. The promise was that Macri would bring the calm, technocratic order of Buenos Aires to Argentina as a whole.

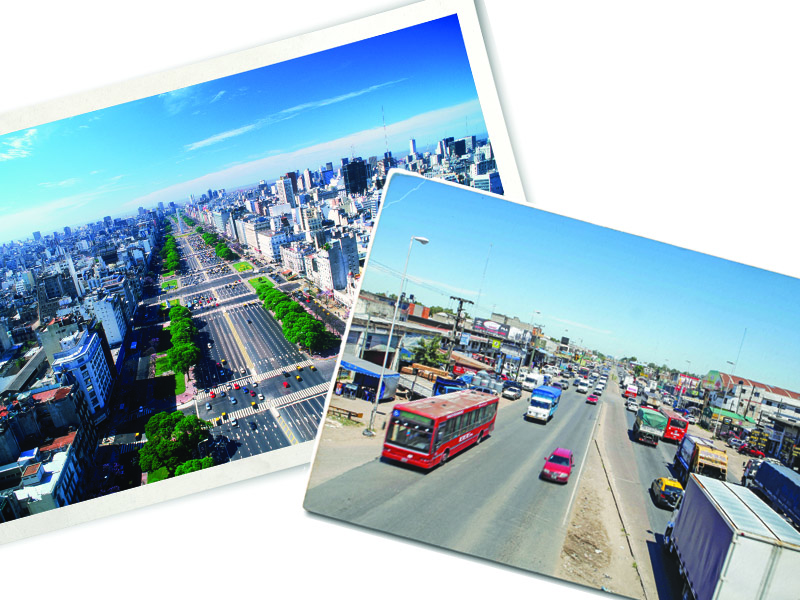

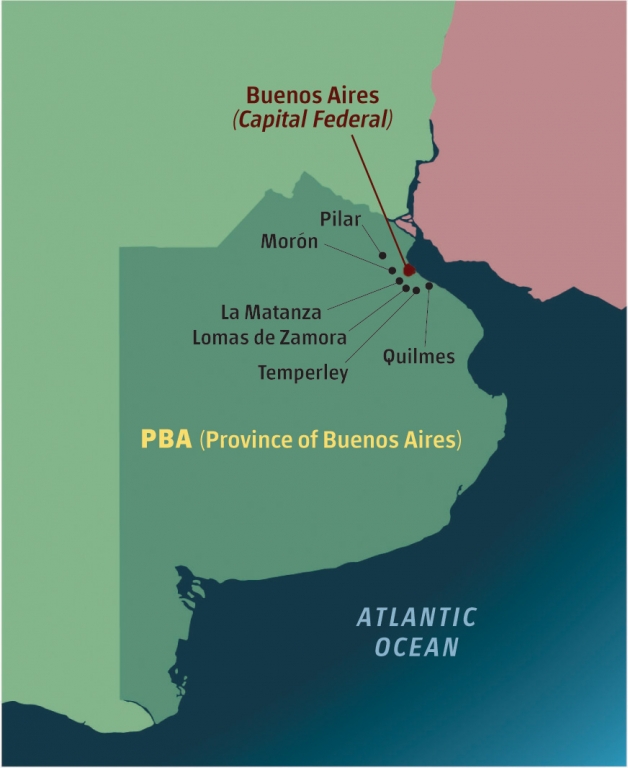

This Buenos Aires, Argentina’s political and business center, is also known as Capital Federal. It has a population of 3 million people and a per capita GDP of about $25,000, roughly equal to that of Portugal. But there is also another Buenos Aires: the province surrounding the city, which carries the same name but is vastly bigger— and poorer. The Province of Buenos Aires, known as PBA, has a population of 15.6 million and a per capita GDP more similar to Jamaica or the Philippines. For decades, PBA has been home to some of Argentina’s worst poverty and crime. And here, unfortunately, it’s still as if la crisis never ended.

Buenos Aires (left) and the city of Lomas de Zamora, just 12 miles away

In some areas of PBA, only one in three adults has a formal job — the rest are unemployed, or labor in the black market. Many roads are unpaved. Floods are frequent and deadly. Entire neighborhoods are controlled by drug gangs, “express kidnappings” and assaults are common, and misery in the bad areas is comparable to the worst Brazilian favelas or Colombian comunas. Hearing this, many outsiders are skeptical: How could a place just 15 miles from the erstwhile “Paris of South America” be so bad? But consider this: In Quilmes, the city for which Argentina’s most popular beer is named, fewer than a quarter of households are connected to the sewage system, while only about half have drinkable water. Overall, in the most populated areas of PBA, roughly 30 percent of households lack basic services — compared to just 1.6 percent in Capital. Malnutrition, poverty, child mortality and homicide rates are all exponentially higher.

The task facing Macri here is formidable — and it will likely determine whether or not his government succeeds. PBA represents by far the biggest pool of votes in Argentina, with about 40 percent of the national total, and it historically leans left. Macri won just enough votes in the province to take the presidency in 2015, as voters hungered for change following 12 years of rule by the Peronist duo of Nestor and Cristina Kirchner. But hopes have now been raised, and if Macri fails to bring the same kind of progress he did to Capital, then kirchnerismo— or something like it — may return in 2019. Fixing PBA “is Macri’s true test,” said Carlos Pagni, a history professor and columnist for La Nación.

The task facing Macri here is formidable — and it will likely determine whether or not his government succeeds. PBA represents by far the biggest pool of votes in Argentina, with about 40 percent of the national total, and it historically leans left. Macri won just enough votes in the province to take the presidency in 2015, as voters hungered for change following 12 years of rule by the Peronist duo of Nestor and Cristina Kirchner. But hopes have now been raised, and if Macri fails to bring the same kind of progress he did to Capital, then kirchnerismo— or something like it — may return in 2019. Fixing PBA “is Macri’s true test,” said Carlos Pagni, a history professor and columnist for La Nación.

The area is a tough nut to crack for someone like Macri, a member of the Davos set who in his 20s was helping his family do real estate deals with Donald Trump. The good news is that in his quest to overhaul PBA, Macri found the perfect ally — a plain-spoken, audacious 43-year-old mother of three, one of the most unique figures in Latin American politics today: María Eugenia Vidal, the province’s new governor.

An Unlikely Rise to Power

At first, no one believed she could win the job.

Vidal isn’t even from PBA — she was born and raised in Capital, and is in many ways a classic product of the city’s middle class. Her father was a cardiologist and her mother was a manager at a bank. Family vacations were taken in a dumpy yellow Fiat with no air conditioning to beach towns like Villa Gesell or Camboriú, Brazil — a 22-hour drive — while listening to cassettes of Fito Paez or Roberto Carlos. La Otra Hechicera (“The Other Sorceress”), a biography by the journalist Ezequiel Spillman, describes a girl who grew up playing volleyball and compulsively drinking mate tea, attended the Catholic University of Argentina (UCA), and married her college sweetheart. Ask Argentines what they like about Vidal, and many will describe her as a chica de barrio. Loosely translated: the girl next door.

Heavily influenced by her grandmother, an Italian immigrant who never finished elementary school and cleaned houses to make ends meet, Vidal showed early signs of a social conscience. But instead of pursuing the path of protests and party activism common among the Argentine left, she took the policy wonk route, studying political science at UCA. By her mid-20s, she was executive director at a think-tank that was trying to chart a center-right path out of la crisis. Macri, then preparing his first run for mayor of Capital, attended an event and saw exactly the kind of young technocrat he needed to build his new political party, the Republican Proposal (PRO).

A polluted drainage ditch in Lomas de Zamora, in PBA

A polluted drainage ditch in Lomas de Zamora, in PBA

Pairing an easy charm with a tireless work ethic and loyalty to the boss, Vidal rose quickly — becoming Capital’s minister of social development, and then the vice-mayor. But there was still little reason to expect bigger things.

By 2013, when Macri was deciding on the PRO’s candidate for the governorship, the kirchneristas seemed vulnerable nationally but at zero risk of losing a province they considered their natural base. By this point, Vidal had moved to a small house in Morón, a city in PBA where her husband was also a rising political star. Yet Peronists had run the province for 28 straight years. Since its formation in 1882, no woman had ever been governor of Buenos Aires. Vidal’s campaign began with so little funding that she spent the initial months just walking around, talking with people, and listening.

Then, a classic case of overreach changed everything. Cristina Kirchner chose as her gubernatorial candidate Aníbal Fernández, a shady, mustachioed figure whom Vidal’s biographer described as “the perfect foil she needed to make history.” Infamous for once claiming Argentina had “fewer poor people than Germany,” Fernández was also dogged by allegations of involvement in drug trafficking (which he vigorously denies). This was explosive in a province that is ground zero for Argentina’s cocaine epidemic. The Catholic and evangelical churches have been competing for members over who can be tougher on drugs and organized crime, said Daniel Bilotta, a journalist based in PBA. Bishops and preachers “were scandalized by Aníbal,” Bilotta said, “and they began to promote Vidal on Sundays.”

Vidal vowed to break up the “mafias,” focusing not only on drugs but the bonaerense, PBA’s notoriously corrupt police force. She also spoke earnestly about her own brushes with crime, including a terrifying 2007 incident near her home in which two armed women tried to pull her youngest child, then a week old, out of his stroller. Only by screaming and throwing herself on top of the baby was Vidal able to save him. In sharing such personal stories, she tapped into the global hunger for a new, more authentic kind of politician. Argentines have a well-earned reputation as one of Latin America’s most cynical nations — especially in politics — but something about Vidal makes them melt. “She’s very pretty, but also very tough,” marveled Juan Manuel Torres, a businessman. That’s a quote I’d normally hesitate to print, except I heard literally dozens of variations of it from men and women, young and old. Another refrain: “She’s just like me.”

Vidal ultimately beat Fernández by five percentage points in October 2015. She dedicated the victory to her grandmother, calling her “the wisest woman I ever knew,” and then got right to work. She purged the provincial prison system — another of PBA’s most crooked organizations — of 132 senior officials and put a former federal prosecutor in charge. She also took charge of the Internal Affairs division of the bonaerense. When the inevitable death threats came, and her bodyguards warned that her house in Morón was too modest and exposed to properly secure, Vidal packed up her kids (she separated from her husband shortly after the election) and moved to a residence on a military base, from which she has commuted for the past year.

Through it all, she has — somehow — retained that light, common touch. The week I was in Argentina, a photo of Vidal (left) eating a salad and talking on her cell phone at McDonald’s, where she had taken her son for lunch, went viral. When I first walked into her office, Vidal was grabbing her calf, wincing in pain but laughing after an unexplained mishap that morning on a treadmill she installed next to her bed. “I’m done with that thing,” she swore in mock fury. “I’ll just use it to hang my clothes.”

Through it all, she has — somehow — retained that light, common touch. The week I was in Argentina, a photo of Vidal (left) eating a salad and talking on her cell phone at McDonald’s, where she had taken her son for lunch, went viral. When I first walked into her office, Vidal was grabbing her calf, wincing in pain but laughing after an unexplained mishap that morning on a treadmill she installed next to her bed. “I’m done with that thing,” she swore in mock fury. “I’ll just use it to hang my clothes.”

I introduced myself, and told her I’d spent the last several days traveling around PBA. That’s when Vidal did something else pretty unusual for a modern politician. “Wait a minute,” she interrupted. “Tell me — what did you see?” And then she sat back on her couch, and listened.

A Long, Slow Decline

Driving around the province, the first thing that struck me were the windows into life a century ago, when exports of chilled beef to Europe made Argentina’s central bank overflow with gold. PBA’s biggest city, with a population of 1.7 million, is named La Matanza — literally, “The Slaughter” — because that’s where cattle were historically taken to meet their maker. Many towns took root on railways built by the British, and have names like Hurlingham and Banfield. My best Argentine friend is from Temperley, and I’ve spent long afternoons there drinking Quilmes beer and playing tennis among its Tudor-style homes and towering eucalyptus trees. Farther from Capital, PBA is an often prosperous agricultural heartland.

Some countries have tough years; Argentina has had eight tough decades. And even in the “good” pockets of PBA, there is no missing the devastating decline. Pilar, 35 miles west of Capital, became a popular destination during the 1990s for weekend homes in closed communities — what the Argentines call “countries” — separated from slums outside by 10-foot walls and razor wire. “We have the best golf courses and polo fields you can imagine, but no green spaces for most of our citizens, and our hospitals and schools were a mess,” Pilar’s mayor, Nicolas Ducoté, told me. He traces this to the collapse of Argentine manufacturing, and a long period when the state simply did not invest in basic infrastructure. Fully 70 percent of Pilar’s households lack drinkable water, he said. La Matanza is so dangerous that I had three taxi drivers refuse to take me there. My friend’s family sold their house in Temperley after a traumatic robbery.

A streetside market in the 2 de Abril neighborhood of Lomas de Zamora

A streetside market in the 2 de Abril neighborhood of Lomas de Zamora

In the aftermath of la crisis, the Kirchner governments tried to bring some relief through social programs, including a conditional cash transfer scheme similar to Bolsa Família in Brazil. These paid families an income of about $50 per child, and helped reduce malnutrition and inequality in PBA and elsewhere. Yet in the decade since, precious few real jobs have materialized to take their place.

I spent a morning in 2 de Abril, a neighborhood of Lomas de Zamora, where the unpaved roads are impassable for buses and ambulances when it’s raining, and addicts and thieves are pervasive when it’s dark. Monica Diaz, a community activist, told me most honest work comes either from an informal market down the street, or a common building where the federal government supplies the sewing machines while the workers — all women— bring fabric to make T-shirts. “We depend on the government,” she told me, “and we aren’t afraid to protest if they won’t open their doors.”

Héctor Aguer, the Catholic archbishop of PBA, said he sometimes sees people who haven’t ever held a job — but have big-screen TVs under their tin roofs. “The previous government used handouts to disguise the lack of job creation,” he told me. “They confused consumerism with development.” Those may sound like the words of a tut-tutting outsider, but it was also a view held by working-class people in places like Merló, another impoverished city. “I remember when there was employment here,” said Ricardo Anaya, 65. “But my sons have never known that world.”

After I relayed all this, Vidal took a deep breath and struck a note of caution. “Our mission is to change the political, economic and social system of the past 30 years. But to think we can do this in four years would be to underestimate the reality,” she said. “We’re changing— we’re beginning to change — the rules of the game. But we’ve started some fights here that we won’t be able to finish.

The fight against organized crime is critical not just for quality of life, but for job creation, Vidal said. “If people see thieves in their neighborhood, or in their government, they’re not going to invest in the future,” she said. I then asked about the threats that forced her to move houses, and she shrugged. “Look, what we’re taking on here are big businesses, and I am hitting them in their pocket.” She then added with a wry smile, “In the province, they don’t usually let those things go.”

Still Waiting on the Economy

Bravery is important, but some worry it may be for naught unless Macri, Vidal and the PRO can turn the economy around. And as 2016 ended, the news was not encouraging. Macri has focused on restoring sanity to public finances — a task so difficult that every non-Peronist Argentine president since 1928 has had his term cut short by either a coup or popular revolt. The current recipe involves austerity, including a rise of up to 500 percent in electricity bills. Inflation has spiked and, as a result, the nationwide poverty rate rose five percentage points to 34 percent by the middle of 2016. Macri promises a healthier economy will attract more investment, and he hosted a flashy “mini-Davos” summit in Capital for 1,600 local and foreign executives in September. But by late in the year, the hemorrhaging had still not stopped. In October alone, the construction industry — key to PBA’s economy — contracted 17 percent, shedding an additional 51,000 jobs.

Marci has tried to battle back, working to improve the business climate but also steering money into social programs: The number of Argentines receiving handouts rose 2.3 percent in 2016, the fastest pace in five years. Aware of the importance of both PBA and Vidal, Macri has also poured money into the province – an extra $1.5 billion in federal funding for the province was recently announced – and seemingly every week a smiling Macri and Vidal seem to be on television together, cutting the ribbon on a new dam or sewer. “Our biggest challenge is to have public works projects that generate more social inclusion” by creating jobs or improving public health, Federico Salvai, one of Vidal’s top aides, told me.

A salesperson waits behind protective bars. High crime is a constant concern in many parts of PBA.

A salesperson waits behind protective bars. High crime is a constant concern in many parts of PBA.

Investors are watching all this closely – and with some skepticism. I spoke to several who attended the September summit, and most outside the energy sector said they’re still not quite ready to bet big on Argentina. Their main concern: that the down economy will lead voters to punish Macri in 2017 legislative elections, and that leftist rule — and maybe even Cristina Kirchner herself — will return after that.

Yet, after spending several weeks reporting this article, I wondered if those investors are underestimating Argentines’ desire for change — and belief in their new leaders. Even amid recession, Macri’s approval rating has remained relatively resilient at about 55 percent, while Vidal’s stands at 61 percent. “People know that tomorrow will be tough, but they’re willing to sacrifice if it will result in something better for their kids,” Vidal told me. That sentiment surely won’t last forever — but it might last long enough. Alberto Kahale, the president of PBA’s main small business association, told me he expected recovery to take hold by April, as interest rates start to come down. A good harvest — which historically eases even Argentina’s worst ills — is also expected around that time.

The final encouraging sign came from a breakfast I had in New York with three provincial legislators — one from the PRO, one from Kirchner’s party, and the other from a third group. The mood was jocular, and they good-naturedly called each other boludo (the semi-vulgar Argentine insult/term of endearment) as they debated the future of their country (and mine). They sharply disagreed about Macri and the legacy of the Kirchners. But there was a consensus that a new, more constructive brand of politics was taking hold in Argentina despite recession and austerity.

“You know, Vidal offers a break from all that,” said the kirchnerista legislator, Hernán Doval, as his colleagues nodded in agreement. “I have to admit: She’s a figure who encourages expectations.”