“They tell us on TV to wash our hands and our clothes – how are people here supposed to do this if they don’t have water or soap?”

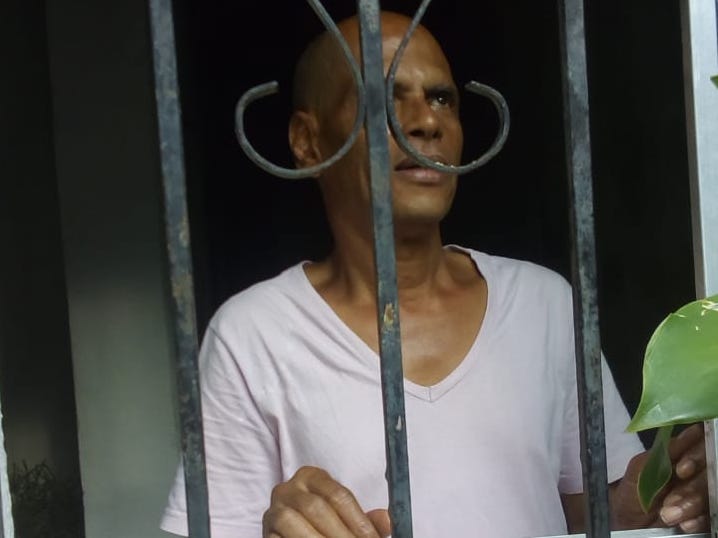

Jorge Luiz Souza, 57, lives in Morro do Andaraí, a favela smack in the middle of a hillside in northern Rio de Janeiro, where residents are struggling to square their already vulnerable situations with the reality of a pandemic that has left many without jobs.

In Mexico, Norma Puchet Mixtega hops a bus – now half empty – to head to work cleaning a furniture store in Mexico City’s upscale Lomas de Chapultepec neighborhood. “Until they tell me not to come, I guess my plan is to keep going. But I need to take precautions,” Puchet told AQ.

These stories repeat across Latin America, as the challenges of living hand-to-mouth during the outbreak are made only more acute on the peripheries of the region’s major cities. And for millions of families who share cramped living quarters or lack running water in their homes, precautions like social distancing and frequent hand washing can seem close to impossible.

In some parts of the region, most notably Mexico and Brazil, the need for daily income – and mixed messages from political leadership – mean that, while streets in wealthier neighborhoods have long since emptied, normal life in places like Morro do Andaraí moves hesitantly onward.

“My neighbor used to cook and deliver meals in offices nearby. Now that everyone is working from home her income is gone,” Souza told AQ. “But when it comes to stopping social activities, people just don’t. There is a pick-up soccer game happening across the street from me right now.”

Souza said a lack of a public attention directed to residents on the periphery has made reacting to the virus more difficult. “The first case in Rio was one month ago, and neither the city, state nor federal government have devised any initiative towards this population,” said Souza.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s dismissal of the dangers of coronavirus haven’t helped. Indeed, as both he and Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador have focused their rhetoric more on limiting economic impact than on preventing illness, both countries have lagged behind others in the region on social distancing recommendations.

According to the Inter-American Development Bank, traffic congestion in Mexico and Brazil had fallen by less than 60% on March 29 from the beginning of the month, compared to around 90% in several of the region’s other major economies.

In those outlying neighborhoods and towns across the region that were quicker to go quiet, the economic impact of the virus has already turned life upside down.

Fernanda Moyano, who lives in Florencio Varela, an informal settlement on the edge of the Buenos Aires city limit, told AQ that her family hadn’t earned any income for two weeks, after her husband lost his job at a metallurgical plant.

“The same night (President Alberto Fernández) announced the total quarantine, my husband was let go from his job,” Moyano told AQ. “His manager texted saying ‘OK muchachos, let’s see what happens in the next few weeks.’”

The Argentine government has taken steps to help communities like Florencio Varela, with Fernández even saying that “the periphery could be our Wuhan.” But the challenges are immense. Government-issued debit cards, for example, are no longer accepted at some local supermarkets, which now only take cash.

A similar set of problems have cropped up in Bosa, a working class neighborhood near the southwestern edge of Bogotá, where residents have mostly stayed at home amid a national quarantine, but are having trouble getting hold of basic goods.

“(The supermarket) is starting to limit the number of products people can buy. They didn’t have any soap or disinfectant either,” resident Andrés González Cuéllar told AQ. “My job can be terminated at any time. It’s a time of crisis for me.”

Peru was quick to institute one of the strictest lockdown in the Americas, with a nightly curfew and a strict stay-at-home order that allows residents out only to buy food or receive medical treatment. Police have since arrested nearly 30,000 people for failing to comply with the lockdown.

For Mariana Elena Carbajal, a nurse who lives with two of her adult sons, one daughter-in-law and three grandkids in Lurín, in southern Lima, that has meant significant hardship.

“Being trapped at home all day is almost as bad as worrying about money,” Carbajal told AQ. “Thank God my oldest is a sereno (a municipal security agent) and is one of the few who can continue to work.”

“It’s only been two days since you could tell there’s been a total quarantine issued,” said Moyano of her Argentine neighborhood. “The thing that changed (two days ago) was fear. On Sunday morning, (our municipality) confirmed 25 cases of the coronavirus.”

—

Benjamin Russell is AQ’s correspondent in Mexico City. Lucia He is a reporter based in Argentina. Follow her on Twitter at @LuciaWeiHe. Simeon Tegel is an independent journalist and analyst based in Lima. Follow him on Twitter at @SimeonTegel.

Additional reporting by Cecilia Tornaghi and Leonie Rauls in New York.