RIO DE JANEIRO – Brazil’s judges have long been among the most generously compensated in the world, with taxpayer-funded privileges – including publicly funded chauffeurs, cars, housing and generous pensions – that would stun their counterparts elsewhere.

These perks have remained immune to the fiscal austerity measures most ordinary Brazilians have faced in light of Brazil’s worst recession in decades.

However, a wave of public criticism has judges pushing back. One particularly contentious privilege in question is the auxilio-moradia, a monthly housing allowance for state and federal judges that they can receive even if they already own property in the cities where they work. While the Supreme Court had planned to revisit the privilege on March 22, and possibly limit access to the allowance, a judges’ union successfully petitioned the court to postpone a ruling on the issue.

At the center of the debate is the cost of the housing benefit. For judges alone, the expense is expected to reach $101.2 million this year, according to research by Augusto Bello de Souza Neto, a budgetary consultant for Brazil’s Senate.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s government continues to navigate a fragile economic recovery. Hospitals lack medical supplies, schools remain closed, police forces are decimated, and once middle-class families have been pushed to the streets. After failing at pension reform, the state needs to cut $4.2 billion from next year’s budget. Public services are likely to be hit hard.

The sense among average Brazilians that their judges are living in an alternate reality has, in turn, fueled a tense media debate about the judiciary’s compensation packages. The branch has come to represent a bloated bureaucracy that weighs down the country.

The population is not taking it anymore, said Matthew M. Taylor, an associate professor at American University in Washington D.C. and an expert on Brazil’s judiciary.

“Brazilians are increasingly questioning what it is that they are paying such a huge fortune for,” he told AQ.

This confoundment has been vocal. A video on YouTube shows a priest singling out the judges and auxilio-moradia in a recent sermon. Last month, the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo’s lead editorial, with the headline “Privileges of Caste,” called out the fact that for each judge, the housing benefit alone exceeded the income of almost 90 percent of the Brazilian public.

Even Car Wash judges Sérgio Moro and Marcelo Bretas, both well-known for their stance against government corruption, haven’t escaped scrutiny. Moro recently acknowledged receiving the housing allowance even though he owns property in Curitiba. Bretas provoked complaints after media reports revealed that he and his wife, also a judge, each receive the benefit even though they live together.

But Brazil’s judges are not budging. On the contrary, hundreds of them, joined by prosecutors, marched in cities across the country on March 15, protesting this “insidious attack,” and in support of what they said was independence, defense of the truth, and “dignity in compensation” according to a statement by Roberto Carvalho Veloso, the president of AJUFE, an association of federal judges that led the act.

Neither Bretas nor Moro attended the demonstrations, according to their press offices.

The protests are further proof of judges’ disconnection from society, said Gil Castello Branco, the founder of Contas Abertas, a non-profit that promotes transparency in government expenditures.

“They are defending the indefensible,” he told AQ.

The housing benefit stems from a 1979 law and was initially for a restricted group of judges. In 2014, however, Supreme Court Justice Luiz Fux, in an individual ruling, extended the law to include all federal and state judges.

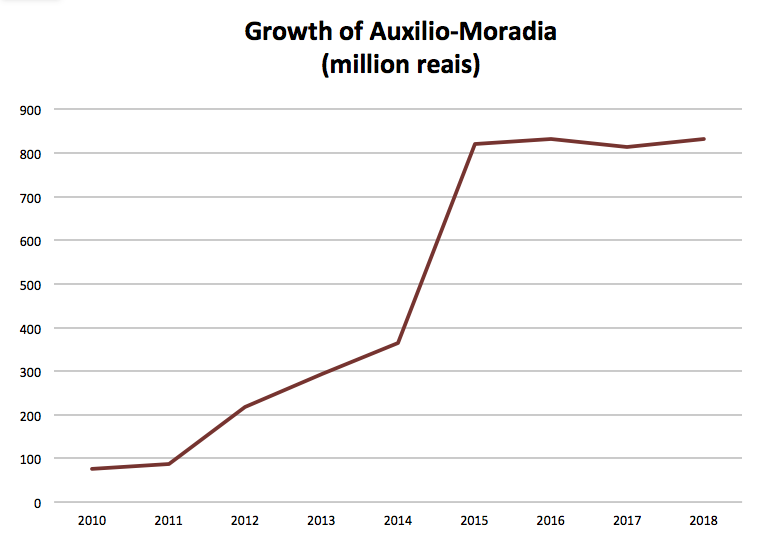

That ruling led to the current budgetary explosion. The cost of the housing benefit for judges grew from $5.2 million in 2014 to $99.4 million in 2017, according to De Souza Neto, the Senate consultant. In the same period, Brazil’s economy shrank by over six percent.

Other independent estimates of the cost of the housing privileges are much higher. According to Contas Abertas, the housing benefit for judges alone has cost Brazilians $939 million since Fux’s ruling.

“The housing benefit has become an insult to the people,” said Castello Branco, in a letter last July to Cármen Lúcia, the president of the Supreme Court .

The debate over the judges’ perks has called attention – and criticism – to the overall cost of the judiciary, which in Brazil consumes 1.2 percent of GDP, in 2014 figures, according to research by Taylor and Luciano Da Ros, a law professor at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

In Spain, the comparable figure is 0.12 percent. Argentina is at 0.13 percent; England and the U.S. are each at 0.14 percent. Germany’s cost is 0.32 percent.

“These are extraordinarily expensive courts,” Taylor told AQ, tying their costs to the benefits.

Note: Graph shows expense for all three branches of government. Figures at ICPA.

Note: Graph shows expense for all three branches of government. Figures at ICPA.

Source: Augusto Bello de Souza Neto/Siga Brasil Paneís

To be sure, the judiciary is not the only beneficiary of the housing benefit. The legislative and executive branches also receive it, and so have little incentive to end it. Costs have grown for all three branches, according to the Senate report by Souza Neto. The financial burden of the executive branch grew eight times between 2010 and 2015 and accounts for the largest amount among the three branches, the report showed.

Over 100 legislators get auxilio-moradia, including Senator Pedro Chaves, who happens to own more than 30 properties, according to Folha de S. Paulo.

The three branches have done very well protecting each other’s privileges so far, said Taylor, but for how much longer remains to be determined.

“The public sector elites are probably due for a reckoning,” he said. “This is unsustainable.”

This piece has been updated to include the postponement of the Supreme Court’s ruling on the housing benefit for judges.

—

Vinod Sreeharsha is a journalist based in Rio de Janeiro.