This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on peace and economic opportunity in Colombia

Few stories better illustrate Mexico’s deep-rooted inequalities — and the broken legacy of its century-old constitution — than the giddy career of William O. Jenkins.

In 1901, this Tennessee farm boy placed his bets on Mexico. Shortly before crossing the Rio Grande, he had eloped from Vanderbilt University with his Southern belle girlfriend. He had a chip on his shoulder: Her patrician family deemed him beneath her station. Before their flight he wrote to her, “I’ll make the last one of them glad some day that they are related to us.”

Jenkins set out to prove himself by making a lot of money, and the pro-business dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz suited his purposes. First, he innovated in textiles; his mill in Puebla pioneered the use of electricity to mass-produce hosiery. Then, already cash-rich when the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, he harnessed the whirlwind and quintupled his fortune, chiefly through property speculation. After the 10 years of fighting, he was worth $5 million.

Jenkins’ meteoric rise could have been halted when revolutionaries unveiled what was arguably the world’s most radical charter — the 1917 Constitution, with its promises of effective suffrage, protections for labor, division of vast estates among the rural poor, and an end to monopolies. Instead, the American would grow still wealthier under the chaotic peace that ensued, in a story that encapsulates potent alliances between business and political elites.

Though the constitution promised a Mexico for the Mexicans, the American built an extensive sugar plantation. While it championed workers, he coopted unions and let his henchmen bump off activists. It tightened rules against monopolies, yet Jenkins developed one in Mexico’s vigorous film industry. It decreed electoral democracy, but he helped finance the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which would rule for 71 years.

And so Jenkins became both an archetypal plutocrat, and the gringo Mexicans most loved to loathe.

A U.S. plutocrat in Mexico

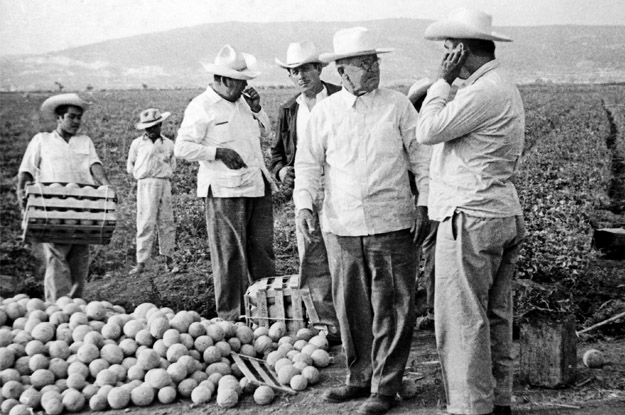

After the Revolution, Jenkins returned to his roots in farming — on a massive scale. In 1921 he foreclosed on Atencingo, a Puebla sugar hacienda, and over the next decade he used predatory lending to bag another eight sugar estates. This gave him the largest landholding in Puebla history, some 200,000 acres.

As he happily tramped the fields, supervising innovations in imported cane, irrigation and fertilizers, Jenkins faced several obstacles. One was his wife, Mary, who never took to Mexico and longed to live in the mansion that Jenkins had built for them in Los Angeles. She wrote a friend, “Mr. Jenkins is down on that pesky old sugar farm so much of the time that I had almost as well be in LA.”

Another was the constitution, whose most famous phrase declared, “Necessary measures shall be taken to divide large landed estates.” These were the great haciendas, properties of the white elite, which had grown at the expense of indigenous villagers. In part, the constitution sought to reverse this process, creating communal farms.

Here Jenkins got lucky because the politicians faced a quandary. After a decade of wartime devastation, agricultural output needed ramping up fast. Álvaro Obregón, the first postwar president, doubted the efficiency of communal agriculture, so he protected haciendas that promised high productivity. These included Atencingo.

A third obstacle consisted of armed peasants known as agraristas who sought swaths of Jenkins’ haciendas, often via land grabs. Several governors tried to back them. But Jenkins was judicious with his pesos. He lent the cash-poor state government money, deterring it from confiscating his cane fields. He made donations to the Catholic Church, acquiring social capital. And he bought off rural bosses who had served as generals under Emiliano Zapata.

With his rings of political influence, Jenkins also eluded several dictates of the constitution’s second-most celebrated section, concerning labor. It forbade the old custom of paying workers in scrip, redeemable at pricey company stores, but when the Great Depression hit, Jenkins did exactly that. It also guaranteed the right to form unions and to strike. But after activists organized Atencingo’s workers, their syndicate was coopted by management. Strikes were rare, and the few that occurred were snuffed out with help from Puebla’s governors.

Jenkins proved no worse a landowner or employer than most wealthy Mexicans. They too bought political protection, coopted unions, fought off agraristas with vigilante posses, and paid dismal wages. They too debilitated the constitution’s vows, helping preserve the gulf between rich and poor. Jenkins drew more flak, however, as he was American.

Monopolizing the silver screen

Monopolies were another f the constitution’s targets. The charter would combat an ancient concentration of riches and protect consumers from gouging. But the measure was unpopular with Mexico’s modernizers, the generals-turned-politicians who frequently gave themselves government contracts — the men skewered in Carlos Fuentes’ The Death of Artemio Cruz.

So the prohibition was almost never applied. Rather, politicians preferred to let the press rail against monopolies in public, while they themselves coddled them in private, often as covert beneficiaries.

Such political theater suited Jenkins, whose instincts — cultivated in the land of Rockefeller — were quite monopolistic. By 1941, he co-owned all of Puebla’s movie houses, and these became launch pads for his greatest venture: two national chains of venues, competing for customers but colluding over fees to distributors and squeezing out rivals. By 1958, the Jenkins Group ran 80 percent of Mexico’s theaters. In prefinancing productions, the consortium controlled much of the native film industry too.

The great irony of the Jenkins Group’s quasimonopoly is that it prospered during the golden age of Mexican cinema. Films such as María Candelaría and La Perla won awards at Cannes and Venice; output surpassed 100 features per year. Mexico’s film industry, the world’s third largest after Hollywood and Bollywood, was a source of national pride. Yet the person who profited from it most was a gringo.

How Jenkins got away with this again owed much to his friendships, most of all with the Ávila Camacho family. The oldest brother, Maximino, was governor of Puebla when Jenkins forged his local dominance; Jenkins had given him an illegal campaign donation, equivalent to $200,000 today. Next oldest was Manuel, who became president in a bitterly close election in 1940, thanks in part to a large campaign loan from the American.

A mixed legacy

At his death in 1963, Jenkins had amassed around $80 million — roughly $600 million in today’s currency, and possibly Mexico’s largest fortune. Outdoing even Andrew Carnegie, Jenkins willed his entire wealth to a foundation he created; it would fund public works in Mexico.

Noblesse oblige was not his only motive. Jenkins also felt deeply guilty for reneging on his promise to Mary to move with her to California. She had died there, alone, 19 years earlier. And the mansion he’d built for her? Jenkins sold it to J. Paul Getty. It was used as the set of the movie Sunset Boulevard.

The Mary Street Jenkins Foundation remains one of Mexico’s largest charities. Jenkins’ legacy, however, was equally that of his actions as employer, monopolist and political sponsor. The landscape that Jenkins helped shape, through personal dynamism and convenient friendships, was one that largely persisted throughout the 20th century and remains in evidence today: industrialized and globalized, but scarcely democratic, routinely corrupt, and deeply unequal.