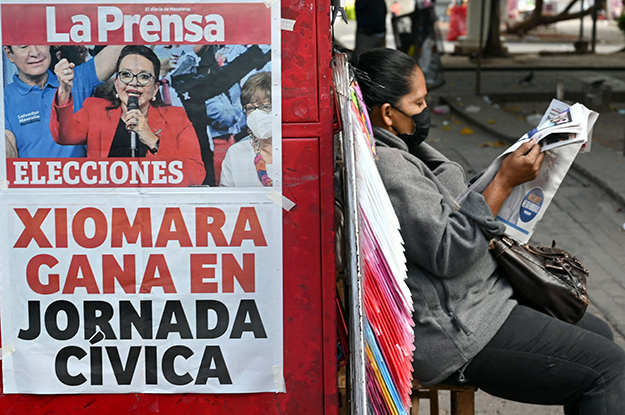

Editor’s note: On November 30, after the publication of this article, the candidate of the ruling National Party, Nasry Asfura, conceded victory to Xiomara Castro.

In a presidential election with the highest turnout in 24 years, Hondurans spoke – and they want change. Of the 68% of eligible citizens that went to the polls on Nov. 28, over half voted to punish the incumbent conservative National Party (PN). If preliminary results stand, Hondurans will elect Xiomara Castro, from the leftist Freedom and Refoundation (LIBRE) party, as the country’s first woman president.

The end of the PN’s 12-year rule—a period marred by corruption scandals, growing ties with drug cartels, and democratic backsliding in this country of 9.5 million people—offers the country an opportunity for a clean start. Unfortunately, Castro’s victory will not automatically put the country on the track to democratic consolidation. And there are five good reasons to fear that the political situation might worsen before getting better.

The most immediate question surrounds the future of President Juan Orlando Hernández. It’s unlikely he will leave office quietly: Hernández and other high-ranking PN officials have been accused of benefiting from drug trafficking dealings, and the Southern District of New York (SDNY) credits Hernández as sponsoring a state drug trafficking syndicate. The president’s younger brother is serving a life sentence for drug trafficking charges in a U.S. federal prison.

Following Castro’s victory, it’s possible the SDNY may indict Hernández on drug trafficking charges and request his extradition. Hernández could seek immunity by taking a guaranteed seat as a former president in the Central American Parliament, but the Honduran Supreme Court can still approve his extradition. For that reason, Hernández might choose to move to Nicaragua, which has become a refuge for other embattled presidents under dictator Daniel Ortega. A few weeks before November’s election, Hernández and Ortega surprisingly agreed to end a long-held diplomatic dispute concerning the Gulf of Fonseca, suggesting that Hernández was trying to mend relations with a potential ally. Following Ortega’s reelection in a sham contest earlier this month, Nicaragua could be a haven for Hernández to avoid extradition to the U.S.

Second, Castro’s ability to govern could be hampered by the outgoing National Party, which has already shown that it will not retreat quietly into the opposition. In 2014, PN lawmakers and allies in the Liberal Party passed a series of late-hour decrees and laws before LIBRE and opposition leader Salvador Nasralla’s deputies took office. The process, known as the “legislative hemorrhage,” sought to maintain privileges for both parties and locked crucial funds. The PN and its allies could try a similar trick to protect themselves from ceding power entirely.

Third, Castro’s husband and former President Manuel Zelaya could prove a thorn in his wife’s side if he attempts to be the real power behind the throne. Zelaya, whose views are further to the left of Castro, remains a polarizing figure after being ousted from the presidency in 2009 when he was trying to reform the constitution to run for immediate reelection (a move that Hernández successfully pulled off in 2017). Being more moderate than her husband, Castro might face a tough choice. But splitting with her own spouse, the undisputed leader of LIBRE, poses high risks. Recent examples in the region provide a cautionary tale. After all, Ecuador’s Lenín Moreno never recovered after turning on predecessor Rafael Correa, Argentina’s Alberto Fernández has painstakingly learned what it means to cross Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and Bolivia’s Luis Arce has avoided clashing publicly with Evo Morales.

Fourth, the alliance between LIBRE and Salvador Nasralla, which proved critical to Castro’s victory, is actually quite fragile. Castro and Nasralla have been friends and foes in the past. In 2013, they rivaled each other in the presidential election and split the opposition vote. In 2017, Castro endorsed Nasralla and ran as his vice presidential candidate, but their coalition broke down soon after they lost – due to vote tampering, they allege. This year, Nasralla backed Castro weeks before the election, but the road to their successful coalition was full of controversies. Nasralla openly accused Zelaya of murder, and Zelaya responded by saying that Nasralla had “surrendered to the U.S.” after the 2017 election. An ad-hoc alliance formed by leaders who have been at each other’s throats for years should always be taken with a degree of caution. Past actions show that a potential LIBRE-Nasralla government coalition will hang by a thread.

Fifth, Castro’s government program has a worrying and ambitious foundational objective. In her first day in office, Castro has vowed to summon a Constitutional Assembly—a long-cherished goal of Zelaya—to draft a new charter. The process will likely increase uncertainty in a country that urgently needs stability and has a recent record of dealing with such issues using extra-constitutional means. In 2009, elites ousted Zelaya when he tried to hold a non-binding referendum to write a new constitution. Unless Castro is more cautious in her approach, she could suffer a similar reception.

A Ray of Hope?

Alternation in power is often one of the healthiest consequences of elections. Castro’s victory is good news after more than a decade of the PN’s ruinous rule. Now, as Hondurans bid farewell to PN governments, a new era is set to begin with Castro at the helm, a president who will have a rare opportunity to set the country on the right track.

The road ahead, however, is uphill and full of obstacles. The incoming administration will have no time for a honeymoon because of the pandemic, growing fiscal debt, limited state capacity, and widespread poverty. At the same time, Castro can expect little cooperation from the PN-led opposition and will steer numerous flanks within her ranks. To succeed, Castro should abstain from pursuing ideologically polarizing foundational projects that could backfire by alienating voters and instead focus on strengthening democratic institutions, the rule of law, and fostering the conditions for much-needed redistribution. Only then will Honduras buck the political and economic decay trend inherited from the PN that has driven millions to seek a better life abroad.

—

Navia is a contributing columnist for Americas Quarterly, professor of liberal studies at NYU and professor of political science at Diego Portales University in Chile.

Perelló is a visiting assistant professor of international studies at Marymount Manhattan College and Ph.D. candidate in politics at The New School for Social Research. You can follow him on Twitter @Lucas_Perello