May 10 is Mother’s Day in Mexico. But this year, it felt more like cause for protest than celebration. In Juárez, Mexico City, Veracruz and around the country, mothers of young women killed or disappeared amid a growing wave of gender violence gathered to give voice to their grief—and demand solutions.

Unfortunately, the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has too often overlooked the most basic steps necessary to ensure women’s safety—and in some cases has undermined them entirely. The good news is that evidence-based solutions do exist, and there are steps the administration can take immediately to start to correct course.

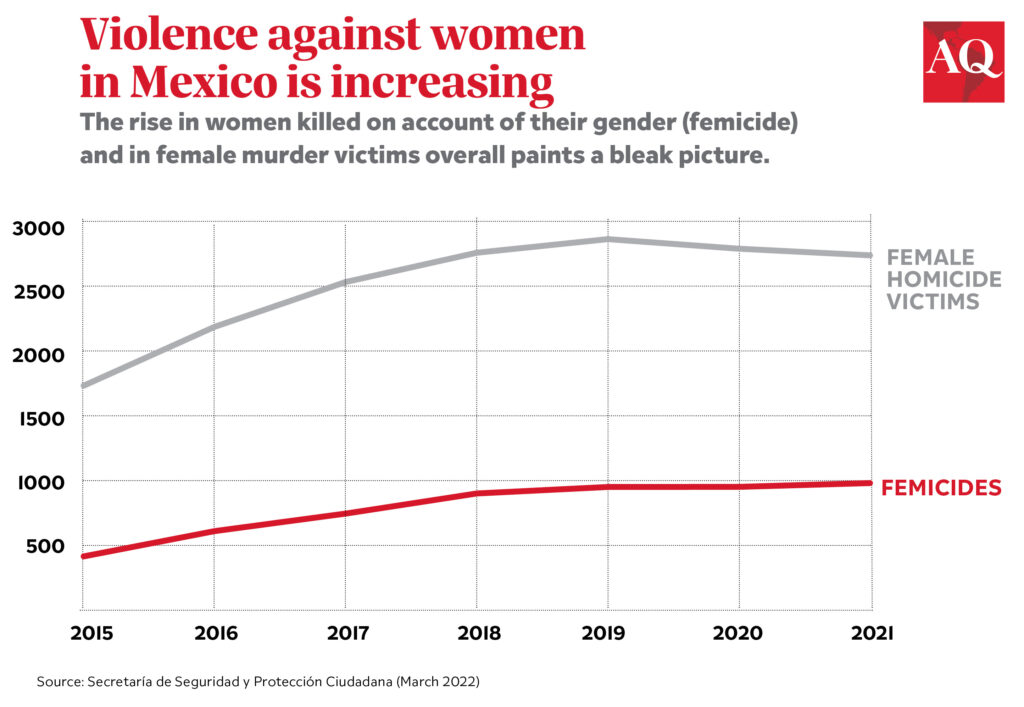

This is true even though the scale of Mexico’s current crisis is hard to overstate. According to official data, 10 women are killed in Mexico every day, and homicide is the leading cause of death for Mexican women between the ages of 15 and 24. Last year, 78.8% of women said they felt unsafe in their home states, and 45.6% felt unsafe in their own neighborhoods. Most concerning, things appear to be getting worse: Between 2015 and 2021, femicides—the intentional killing of women because of their gender—increased 137%, according to official figures.

Evaluating public policy is rarely a black and white exercise, but it’s worth examining what the López Obrador administration has done in response to the crisis, and what it could do better. There’s no panacea in addressing gender violence, but there is one major prerequisite for protecting women on which Mexico’s government has fallen far short: the social safety net.

Evidence from around the world shows how social programs aimed at promoting gender equality also provide women with the financial independence they need to escape situations that put them at risk (an abusive marriage, for example). But while López Obrador came into office on a promise to reinvigorate and strengthen programs for the most vulnerable, his government has done much to tear down the social infrastructure designed with women in mind.

His government, for example, has changed the way the state provides support for parents of young children. This has been to women’s detriment. In Mexico, as in much of the world, women are often expected to bear most of the responsibility for raising children. In this context, the availability of free or government-subsidized childcare can help women participate in the workforce and, in turn, have the financial means to escape violent situations at home.

In his first year in office, ostensibly to tackle corruption, López Obrador cut the budget for a program to subsidize childcare for working women almost in half. As an alternative, the administration proposed giving funds directly to families. But as a host of civil society organizations made clear, the approach served only to reinforce traditional stereotypes that enable the professional development of men while keeping women at home.

An even more immediate example is in the administration’s management of women’s shelters. In early 2019, again under the argument of tackling corruption, the López Obrador administration sought to cancel subsidies for shelters that provide services for women and children fleeing violence. Again, direct cash transfers were the proposed alternative. After a significant backlash from NGOs, the media and some public officials—who argued, using the hashtag #AusteridadMachista, that women fleeing violence required a safe space instead of cash—the government backtracked. But the proposal itself delayed funding and led to the closure of several shelters all the same.

The effects of this weakening of the social safety net for women were exacerbated by COVID-19. As documented by the feminist organization EQUIS Justicia, female homicide and 911 calls related to sexual, gender and domestic violence increased significantly during the pandemic. Even so, the branch of the attorney general’s office charged with responding to violence against women saw its budget cut by 73% in 2020. Civil society organizations and public officials tasked with protecting women were forced to do a lot more with less.

The administration does not appear to have learned lessons from this experience. As analyzed by the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a private research center, federal funding for programs designed to address gender violence and victim assistance actually fell by 0.6% in 2022. The National Institute for Women, a government agency designed to assist other federal agencies in incorporating a gender perspective into their programs, saw its budget rise just 0.8% from 2021.

To be sure, violence against women did not begin under the López Obrador administration. Nor were programs promoting gender equality enacted in previous administrations without significant fault (there is always room for improvement). But the steps the government has taken so far to protect women have often been at best misguided.

In December 2021, for example, the government launched its Comprehensive Program for Preventing, Addressing, Punishing and Eradicating Violence Against Women. The plan was tepidly received, in part because it overlooks the effects of COVID-19 on violence against women, according to activists. An in-depth report by news site Página3 further notes that the government’s plan lacks proprietary funding, meaning that each agency that participates in the program has to cover the costs of implementing, operating and monitoring its own projects.

To be sure, it’s not all bad news. Mexico recently earned an important victory at the United Nations by passing a resolution titled “Strengthening international cooperation to address the links between illicit drug trafficking and illicit firearms trafficking.” The resolution calls on Member states to “mainstream a gender perspective in preventing, combatting, and eradicating those crimes.” If taken seriously and incorporated into domestic policy, this has potential to reduce violence against women not only in Mexico, but in the rest of the world as well.

Ultimately, gender violence won’t be solved by government programs alone. Culture and consciousness matter, and women in Mexico are still far too often blamed for the violence they suffer. A recent poll by newspaper Reforma shows 69% of the population believes “feminism has gone too far,” 38% agree with the statement that “sometimes women put themselves in risky situations and that is why they get hurt,” and 34% agree with the statement that “women who get drunk are looking for trouble.”

But when women in Mexico protest government inaction, we are not only enraged about the daily violences (yes, plural) we face, but also the systemic institutional failure that has become a pervasive characteristic of Mexican politics vis-à-vis women and girls.

In 2002, the case of three women killed in Mexico was brought before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and in 2009 the Court found Mexico in violation of human rights obligations under the American Convention of Human Rights and the Convention of Belem do Pará. The case, known as “Campo Algodonero,” after the cotton field where the remains of the women were found, required Mexico to make systemic changes to prevent more gender-based violence. The ruling does not ask Mexico to reinvent the wheel. International standards have proven successful in the prevention, punishment and reduction of violence against women elsewhere in the world. Mexico has a plethora of civil society organizations and experts ready to work with the government in the design and implementation of effective public policies. Women are simply asking for the doors of Palacio Nacional to be opened, instead of barricaded, when we insist on our right to life.

—

Farfán-Méndez, Ph.D., is head of security research programs and co-founder of the Mexico Violence Resource Project at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California San Diego.