Part of a continuing series on how Latin America can overcome a decade of slow economic growth.

Judging by the reaction of financial markets, the Brazilian economy started the year at high speed. The real is among the world’s best-performing currencies so far in 2019 and the main stock market index Ibovespa hit a string of record highs leading into last week, when it broke the 97,000-point mark. Future interest rates have fallen sharply.

Foreign investors are buying in as well. The premium demanded as compensation for the inherent risk of buying Brazilian bonds, the Credit Default Swap rate (CDS), that in September was above 310 basis points has fallen to around 180 basis points, a range close to that of emerging countries with an investment-grade seal.

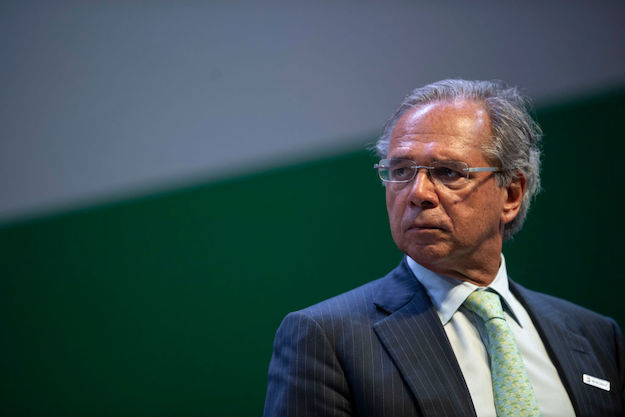

Brazil’s new economy minister, Paulo Guedes, is at the heart of markets’ optimism. Starting with his inaugural speech, Guedes’ priorities have been music to financial investors’ ears. He proposes “fiscal walls” to sustain the 20-year public spending ceiling mandated by a constitutional amendment approved by Congress in 2016. These walls would consist of a public expenditure review with substantial pension reform, extensive privatizations – both as a source of extra proceeds and to re-focus companies on their core missions – a simplified tax code and, overall, an improvement of Brazil’s business environment.

There are nevertheless two major “buts.” Current optimism with financial assets is based on confidence that the entire Bolsonaro administration and Congress will move forward along the fiscal adjustment path. Current financial assets already reflect such a belief and we may see further highs as steps are taken down the road. But if the administration or Congress fails to act, or if the measures they take are perceived as weak, confidence may dissipate and bring down asset prices.

The second “but” has to do with the real economy, where private investment, income growth and, with a time lag, job creation take place. There is a stark contrast between the top floor of asset prices and the ground floor of the real economy. Even though agriculture is poised to yield a third super-harvest in a row and mining has maintained reasonable stability since the end of the recession, manufacturing has wobbled, and construction has performed unfavorably since 2016.

Then there is the labor market. Priscilla Burity, in a BTGPactual report, shows that the underlying labor market has crossed a patch rougher than what the headline unemployment rate may suggest. In big cities, unemployment rates are higher than national ones and have not trended down. The share of discouraged workers out of the labor force is near record highs and labor underutilization has risen since the first quarter of 2017. Even assuming annual GDP growth at 2.5 percent, single-digit unemployment rates are not expected before 2021. And an improvement of labor market conditions is necessary to underpin a virtuous cycle of credit and higher private spending.

At the beginning of 2018, conditions seemed robust enough for an acceleration of economic growth. Debt levels for families and companies had come down, interest rates were low and private banks’ ability and willingness to lend money was there. But the actual GDP performance has disappointed. Business confidence was never high enough to lift investments and, in an election year marked by political polarization, the private sector adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

Now the starting point is again one of higher confidence on a fiscal adjustment, while the overall scenario is still of lower household and corporate debt levels, low interest rates, easier financial conditions and idle capacity, including in the labor market. Growth forecasts are in the range of 2.5 percent to 3.0 percent for 2019-2020 with higher expectations for some virtuous cycle between new credit, increased business expenditures and a more active consumer outweighing the fiscal retrenchment.

The bottom-line for 2019 is straightforward. Either confidence in those fiscal walls is reassured and market optimism trickles down to the real economy, or the risks of a crash mounts – particularly as the global scenario looks riskier than in previous years. Given the current landscape, Brazil better build those walls fast!