At a recent Mining Summit held by the Financial Times, Ivan Glasenberg, Glencore’s CEO, announced that the El Cerrejón mine in Colombia, the world’s largest open pit coal production facility, will shut down in 2031. The same will possibly happen with other coal mines in Latin America. Thousands of jobs will be lost– not to mention tax revenue and royalties, as well as billions of dollars in coal and iron-ore exports, in countries such as Brazil and Colombia.

It should come as no surprise that the large multinational mining companies are announcing significant reductions – up to 30% in the case of Glencore – in carbon emissions. This is more than welcomed by humanity. One after another, mining companies are looking to get out of coal to invest in minerals such as copper, cobalt and nickel, necessary for the energy transition, including electric vehicles.

What is surprising is how badly Latin America is preparing to face that reality. After the era of expansion in fossil fuels, especially oil and coal, what will be the region’s new economic bet? Which are the new engines that will support development in Latin America?

A week after Glasenberg’s remarks, Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s new prime minister, set 2050 as the safe date for his country to achieve carbon neutrality. To get there – without using nuclear energy, which the Japanese people do not want to know anything about after the Fukushima disaster – his government announced the formation of a council to consolidate Japan as a world leader in the energy of ammonia, a chemical composed of an atom of nitrogen and three atoms of hydrogen. The reality is that it is a clean fuel and, in addition, with more energy than hydrogen, and slightly more than one third of the energy of gasoline, per unit of volume.

The interesting thing is that Latin America could be a world leader in its production.

Japan will be responsible for developing the technology and supply chains. In fact, NYK, the Japanese shipping company, is developing vessels that not only transport ammonia, but use it as fuel.

These two announcements, one in London and the other in Tokyo, apparently disconnected from each other, may hold keys to Latin America’s future development and, especially, to its highly elusive industrialization. But the region is not alone in this race: Australia wants to take the leadership of the “ammonia economy”.

The fundamental input for a development of this nature is the production of hydrogen, which is traditionally obtained with technologies that use fossil fuels – the so-called “grey hydrogen” – and which, therefore, do not solve climate change. Some countries – especially those that are rich in oil and gas – are developing blue hydrogen, which captures CO2. The problem with blue hydrogen is that the available technologies are very expensive and require massive deployments of capital. However, this is an option that countries such as Venezuela – obviously in a post-Maduro scenario – could consider with the engagement of international investors.

But where Latin America definitely has an edge is in the production of “green hydrogen”, which is produced with technologies that use the sun, wind and water, precisely the resources that the region has in abundance.

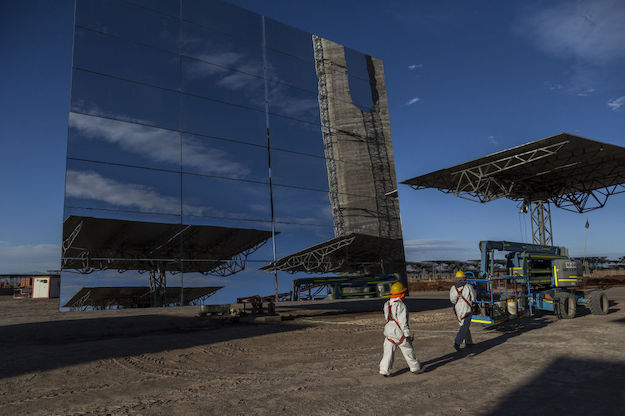

This may sound like science fiction, but it is not. Chile is already thinking of using solar energy from the Atacama Desert to produce hydrogen, convert it into ammonia and send it to Japan from Antofagasta. Colombia could do the same, from Puerto Brisa and Puerto Bolívar, the two ports in La Guajira, which at the outset imposes the extra cost of crossing the Panama Canal. However, wind and solar energy complement each other very well in the Guajira Peninsula, which can produce electricity – the main source of hydrogen – at a lower cost than Chile.

The Inter-American Development Bank and CAF should seriously think about supporting countries with a comprehensive study on the subject. This is an interesting option that needs to be seriously explored. Chile’s energy ministry has already convened a commission to explore the topic, including academics and business. Other countries should do the same.

Latin America is not going to come out of the pandemic crisis on the coattails of a China-led new commodities boom. Innovation in new sectors that will transform renewable energy – the region’s greatest advantage – into manufacturing products and exports is what is needed.

Let’s not forget that the fossil fuels industries emerged in the region decades ago as the product of a public-private initiatives. The new development bets will require, once again, an active role from governments.

Note: If you want to join, my colleague Julio Friedmann, a Senior Scholar at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, and one the world’s leading experts in the field, will talk about this on November 23 at 2:00 pm ET.

—

Cárdenas is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and was Colombia’s Finance Minister (2012-2018). Follow him on Twitter @MauricioCard