This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on closing the gender gap.

When entering public life, Jessica Ortega — a Mexican politician with the Movimiento Ciudadano party and a mother — repeatedly faced the same question: Can she really be these two things at the same time? Her private life became a public matter to many around her, including both party colleagues and opposing forces. “Women like me, who have decided to participate in the political life of our country but who have also decided to have children and start a family, are socially stigmatized,” Ortega told AQ.

She is certainly not alone. Gender stereotypes are one of several reasons why women in Latin America and the Caribbean remain politically underrepresented. Today, only two heads of state and a mere 15.5% of mayors and 27.3% of councilmembers are women. Although the Americas are second only to the Nordic countries, with 31.8% representation in their legislatures, that is far from the 50% they represent in the population and in the pool of registered voters.

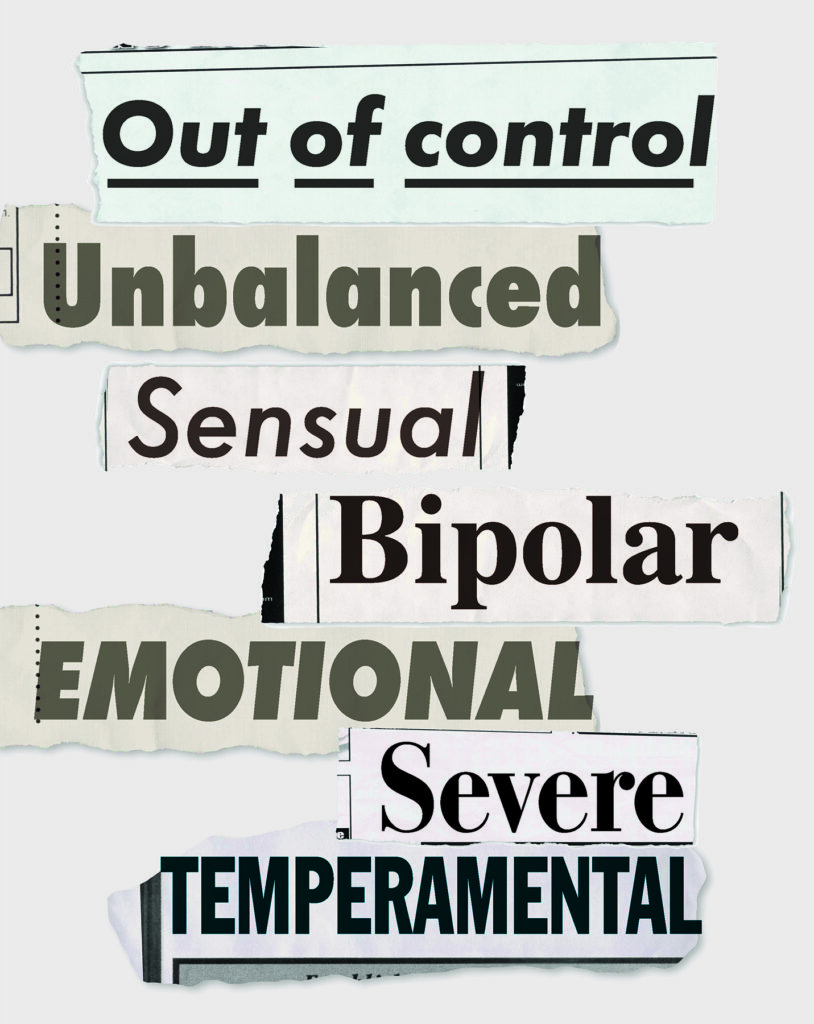

Women who run for office face questions almost unimaginable to male candidates, have a harder time securing campaign funds and deal with misogynistic stereotypes — frequently from their colleagues.

Interviews with female politicians and campaign managers from throughout the region afforded us a better understanding of why it is still so hard for women to run for office in Latin America. Yet some innovative solutions can help female candidates become more competitive.

Questions from all sides

One of the first barriers that candidates confront is the public perception of female leadership and whether a woman can actually get elected. In Latin America, fewer than one out of three citizens say they strongly reject the idea that men make better political leaders than women. Female politicians “face more resistance and prejudice from citizens regarding their leadership capacity” than their male counterparts, noted Argentine political consultant and women’s leadership expert Virginia García-Beaudoux.

Potential voters also have to overcome “the view that a woman has no chance of winning or ruling a country,” said Armando Briquet, a Venezuelan campaign expert who has worked with several female legislative, gubernatorial and presidential candidates across Latin America. The notion that women are less capable of winning can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy. “Since she ‘can’t win,’ many vote for other options even if they like her candidacy,” Briquet said.

The greatest resistance to women in politics often comes from their own parties. Placement on party lists is a determining factor for electoral success. Daniela Chacón, former vice mayor of Quito, noted that all too often women are the “second in the list” — like herself — because “you have to follow party guidelines.”

In some cases, sexism is very explicit. When running for the Honduran Congress, Johana Bermudez’s highly effective campaign caused her to jump from the 227th place on her party list to fourth based on her number of votes. A colleague of hers — who had fewer academic accomplishments and less experience — had gone from 200th place to second. “No one asked him questions about how he did it. Instead, my own party colleagues started asking me ‘Who did you pay, Doctora? Who did you sleep with, Doctora?’ Why? Because they cannot conceive that a woman in the party could achieve these results based on her charisma, talent, discipline and organized work.”

Unequal and sexist media coverage often reinforces these perceptions. The Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) found that out of 22,000 articles analyzed in 2015, women were covered as news subjects in only 24%. According to the GMMP’s Latin American report, “Women were represented mainly in traditional roles, social and health issues,” and the media identified women with family relationships three times more than they did men. “We are evaluated based on gender roles: if we are good mothers, wives or daughters, our physical appearance, our personal relationships,” Mexican Congresswoman Martha Tagle told AQ.

Female candidates also face barriers to financing their campaigns. In August 2019 we conducted a regionwide online poll via the Latin American Political Reform Project where, unsurprisingly, almost 50% of the male and female politicians surveyed said there is a gender gap in the distribution of campaign funding within parties. They also observed that women have more limited access to financing networks compared to men, frequently pulling from their personal funds or relying on donations from their families.

Leveling the playing field

In recent years, Latin America has experimented with mechanisms to correct women’s political underrepresentation. Public financing is one of the most powerful policy tools available. Panama, Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, Brazil and Honduras have allocated funds for women’s leadership training. The Brazilian government indirectly finances women’s campaigns by providing free airtime specifically for female candidates at the federal level. Additional state funding goes to Chilean and Costa Rican political parties that manage to get women elected.

Crowdfunding, or online fundraising for women candidates, has emerged as an alternative to targeted public financing. In the 2018 Mexican elections, leaders from government, academia and civil society launched a fund that covered all legal and administrative fees for women candidates who faced gender-based attacks.

Others have successfully targeted gender bias in the media. Training programs can help journalists become aware of their prejudices. In 2017, the National Electoral Institute of Mexico, along with civil society organizations, trained journalists to avoid personal questions, stereotypes and double standards so they could cover women and men equally.

Female candidates and their campaign managers must realize the obvious: Being a woman can actually be a comparative advantage when running for public office. This can reduce incentives for women to “masculinize themselves” in the attempt to deflect discrimination. Fair electoral contests in Latin America depend on normalizing women running as women.

__

Muñoz-Pogossian is the director of social inclusion at the Organization of American States. Views are her own. Freidenberg is a researcher at the Legal Research Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.