This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on China and Latin America | Leer en español

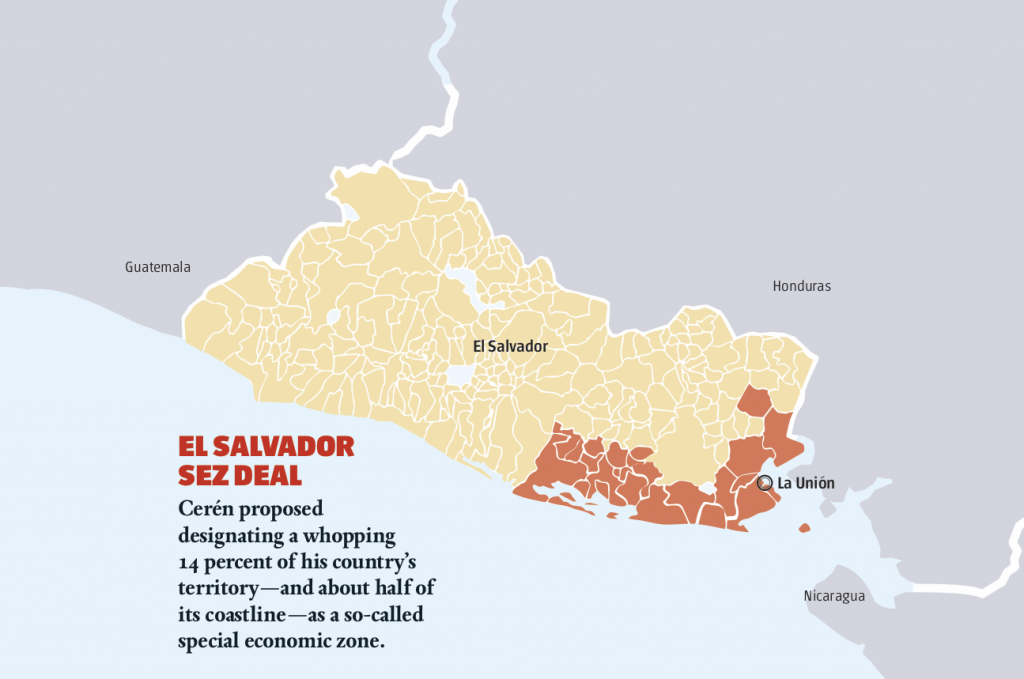

Last July, El Salvador’s President Salvador Sánchez Cerén proposed designating a whopping 14% of his country’s territory — and about half of its coastline — as a so-called special economic zone (SEZ).

SEZs are typically unremarkable, filled with tax breaks and incentives for everything from renewable energy to agricultural investment. But this one looked like a big diplomatic gamble: Amid the Donald Trump administration’s escalating trade war with China, Céren’s SEZ appeared designed specifically to favor Beijing.

One provision in particular had the markings of a sweetheart deal, barring any company already paying taxes in El Salvador from buying into the SEZ. That meant that U.S. firms such as Hanes — one of El Salvador’s largest employers — would be unable to take part.

The Chinese had recently shown interest in other Salvadoran investments, including a major port concession — on land that would now be included in the SEZ. Shortly after the proposal was made public, U.S. Ambassador Jean Manes said in a TV interview that she was “alarmed by China’s strategic expansion” in Central America and suggested China’s interest in the port had both economic and military aims.

“China is trying to find weak points in the region,” Manes said.

Then came the bombshell. On August 20, about a month after proposing the SEZ, Cerén announced that El Salvador would cut its longstanding ties to Taiwan and recognize Beijing instead.

The Salvadoran press went into a frenzy: Just six months before a general election that the governing FMLN seemed set to lose, the government had suddenly broken diplomatic relations with one of the country’s most important foreign donors and trading partners. It wasn’t hard to imagine a quid pro quo — especially given that the SEZ’s proposed territory roughly corresponded to one of the FMLN’s last remaining political strongholds.

“There was very little information coming from the government about how long the negotiations had been going on, how they had taken place, and what the supposed benefits were going to be,” said Sergio Araúz, a political reporter for Salvadoran news site El Faro. “In the political vacuum you started to hear plenty of rumors.”

Cerén’s government denied any wrongdoing, or that China had dictated terms of the SEZ. The potential economic benefits for El Salvador, the FMLN’s leaders said, were obvious.

The SEZ controversy, which is still ongoing, is just one example of how Central America has become a particularly important theater for China. Beijing’s interest in the region is partly about its longstanding rivalry with Taiwan — Guatemala, Honduras, Belize and Nicaragua are among just 17 countries globally that still recognize what China regards as a breakaway province. But Chinese investors today are moving beyond diplomatic concerns and even commodities to invest in infrastructure, transportation, communications and more.

“The commercial relationship between China and the Central American and Caribbean countries … is morphing into a new, deeper relationship,” said Carlos Murillo, a professor of government and public policy at the University of Costa Rica.

That expansion has yielded mixed results. In Nicaragua, a quixotic Chinese plan to build a cross-isthmus canal never materialized. In March, Panama’s President Juan Carlos Varela announced that the first phase of a high-speed rail project, financed and built by a Chinese consortium, would cost $4.1 billion and be finished in six years.

Costa Rica recognized China in 2007 and was rewarded with a $105 million stadium project in San José, though it was Chinese workers who built it, using mostly Chinese materials. CHINAFECC, the company behind the project, used the investment to make headway in the real estate sector, Murillo said.

China’s economic and diplomatic approach has left governments feeling caught between the proximity and clout of Washington and the possibility of limitless investment from Beijing.

“China offers infrastructure, tourism, investment and jobs unlike any other country,” said Enrique Dussel Peters, the director of the Center for China-Mexico Studies at Mexico City’s UNAM university. “But it’s a package deal … the countries that benefit most from Chinese relations will be those that fully understand what it means to have China as a partner.”

Where on that scale El Salvador will end up is still an open question.

Around the time of Cerén’s announcement, it emerged that APX, the Chinese consortium involved in the port concession, had also been behind the planned purchase of two small islands nearby, known as the Pericos, as well as several plots of land in and around the port zone.

As these and other details about Chinese interests in the country were revealed, the tide of public opinion appeared to turn against the break with Taiwan. One poll, taken in October by the Technological University’s Center for Research and Public Opinion, suggested 74% of Salvadorans thought it was a poor decision.

Since then, El Salvador’s congress has revised the SEZ proposal, but seems in no rush to pass it into law. In August the attorney general’s office opened an investigation and blocked any proposed sale of the Pericos islands.

Last October’s presidential election has cast the project further into doubt.

Nayib Bukele, who won the presidency with 53% of the vote, has embraced the Trump administration wholeheartedly in the weeks before his inauguration. That includes a March meeting with National Security Advisor John Bolton and a visit to the Heritage Foundation during which Bukele said, “China doesn’t respect the rules” and “meddles in democracy.”

Many now speculate that Bukele may take the extraordinary step of reversing the FMLN’s decision and rerecognizing Taiwan after he takes office on June 1.

China’s foreign ministry said in a statement in March that relations with El Salvador had been “hard-won” and they were sure Bukele would “make the right choice.” But even if El Salvador’s new president turns his back on Beijing, Chinese interests in Central America seem primed to keep growing.

“China’s style isn’t confrontational,” Murillo said. “It’s just seeping in, stadium by stadium, surveillance system by surveillance system. The million-dollar question is if (Central America) stands to gain.”

—

Russell is a senior editor and correspondent in Mexico City for Americas Quarterly