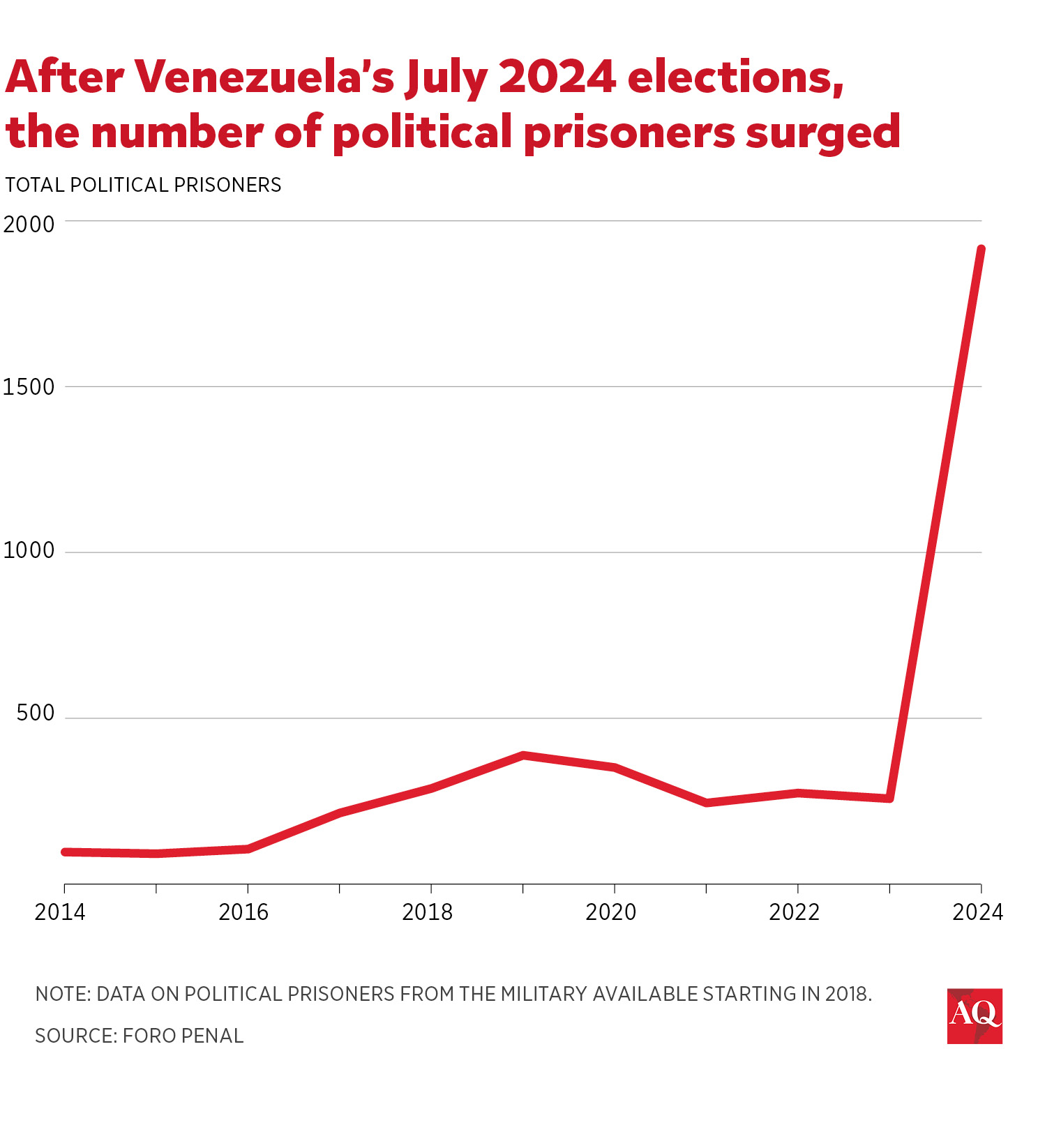

CARACAS – Since Nicolás Maduro decided to bypass the people’s will in the July 28 election, Venezuela has been through tragic times. The country’s authoritarian regime has now imprisoned close to 2,000 citizens for political dissent, seeking to obliterate the opposition with old and new methods. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has called these mass arrests “state terrorism,” raising tensions in a nation already immersed in a dramatic crisis.

The open political repression is giving Venezuela an ominous regional title; it is currently the country with the largest number of political prisoners in the Western Hemisphere, surpassing Cuba’s 1,113 and Nicaragua’s 147 citizens incarcerated for their ideas and beliefs.

As of October 22, according to data from Foro Penal, a Caracas-based NGO tracking political dissent in the country, there were 1,953 political prisoners, an astonishing year-on-year increase of 745%. Is this a temporary situation resulting directly from the controversy over the July election? Or is it the beginning of a new and unpredictable dark period of repression for Venezuela? The answer to these questions is yet unknown. But the independent UN mission in Venezuela has described the dictatorship’s strategy as the “reactivation and intensification of the harshest and most violent modality of its repressive machinery,” with Maduro’s regime working ferociously to cover up the actual vote count, which, three months after the contest, has not been made public.

To control popular discontent, the dictatorship crushed more than 210 protests nationwide on July 29, and in just two days, the regime killed 24 people, the bloodiest period of crowd repression in years. After the immediate repression following the fraudulent election, the crackdown on the opposition has continued at all levels, with authorities arresting citizens without warrants —and denying detainees access to a proper legal defense— followed by lengthy pretrial detentions. On October 25, Edwin Santos, a regional leader of the opposition party Voluntad Popular, was found dead in the Western state of Apure after officials of the military counter-intelligence agency (SEBIN) had detained him two days earlier. His suspicious death was labeled as a “murder” by Voluntad Popular and stirred anger among leaders of the Unitary Platform, which agglutinates most of the organization opposed to the regime. Venezuelan authorities said the death was an accident.

Political arrests before and after elections

Foro Penal reports that the average number of people detained for political reasons in Venezuela between 2014 and 2023 was 250 yearly. That figure did not change significantly in 2017, when massive and uninterrupted protests over four months left at least 140 people dead. During those nine years, the UN Mission determined in a report, the repressive strategy of the Maduro government consisted of a combination of “hard” and “soft” mechanisms. According to the experts’ analysis, the authorities regularly used violent methods until the massive protests of 2019. From then on, the regime favored “soft” and selective methods, which achieved the desired “chilling effect” on society.

The detention and incarceration of lawyer and human rights defender Rocío San Miguel, founder of the NGO Control Ciudadano, is emblematic of the latter. In February of this year, San Miguel was arrested along with five members of her family. In the words of a human rights defender who asked to remain anonymous, “Rocío’s arrest was a tough blow for the human rights movement. Since that day, we feel vulnerable, and we watch every word we say to the media.” Her case and imprisonment remain a riddle.

After the election, the regime seems to have substituted selective repression for a full-scale crackdown. On August 1, Maduro announced that 2,200 people should be detained to put an end to the protests. Since that date, 21 different police and military agencies have carried out arbitrary detentions that, according to Foro Penal, were done without a court order and without clear crimes having been committed by the detained.

So far, 69 adolescents have been detained, suffering the same fate as adult prisoners. They have been temporarily disappeared, tortured, and held in inhumane conditions while denied legal representation by lawyers they trust and subjected to seeing their relatives humiliated during their visits.

Miguel Urbina, 16, is an example of this post-election repression. He was arrested at the door of his home and accused of having participated in acts of vandalism against a police property in Caracas. He told his mother, Theany Urbina, that he had been tortured with electricity to force him to record a video in which he confessed to the charges against him. Men and women had also beaten him.

Due to the massive number of detentions Maduro ordered authorities to repurpose maximum security prisons for common criminals, far from any major city. Meanwhile, Maduro has sordidly mocked the detained. In August, he riffed on the lyrics of a traditional Venezuelan Christmas tune to sing, “Tun tun, no seas llorón, tú te vas a Tocorón.” (“Don’t be a crybaby, you’re going to Tocorón (one of the prisons.”)

Venezuela’s civil society, including human rights organizations, is overwhelmed and powerless to help the relatives. Kennedy Tejada, lawyer for Foro Penal, was arrested on August 2 when he asked about the status of detainees in Carabobo state. From then on, the organizations ordered their lawyers to avoid approaching the detention centers. Instead, they gather information on the situation to send to international human rights organizations and seek assistance for the relatives of the detainees.

Tejada’s case reflects the obstacles that detainees, including adolescents, face in having a legal defense they trust. The absence of public information, as well as the fears of family members, prevent us from knowing the legal status of the detainees or how many of them receive a final sentence.

The role of the international community

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) stated in a harsh communiqué on August 15 that “the regime in power is sowing terror as a tool to silence the public and perpetuate the authoritarian regime.”

All available evidence suggests that Maduro will be sworn in for a new six-year presidential term on January 10, 2025. After diplomatic efforts to achieve a negotiated transition to democracy failed, the international community must prepare to establish pressure and advocacy mechanisms to mitigate and, in the best case, prevent future human rights violations.

Colombia and Brazil—two countries that the Miraflores Palace listens to—could play a fundamental role. However, presidents Gustavo Petro and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva should consider a broader range of proposals.

Beyond these positions, the international community must maintain mechanisms for protecting human rights, such as the UN Mission and the role of the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights. If Maduro ultimately assumes a new presidential term based on repression and not on popular support, civil liberties will be at their lowest level since 1958, when the country’s last dictatorship ended. The question is whether a new Chavista government will be sustainable over the next six years—and whether the country’s prisons will continue to be cleared of common criminals to make room for political dissidents with unknown and unpredictable fates.