Correction appended below.

CARACAS — A year ago, a squall of sheer economic optimism swirled through Venezuela’s capital. The Hard Rock Café reopened in December, a new Ferrari dealership dazzled viewers from a glassy new tower and around 200 new restaurants popped up around the city. After eight years of economic contraction, Venezuela’s GDP started to grow again, hyperinflation abated, and food shortages ended.

The mild recovery resulted from a turnaround in Nicolás Maduro’s economic policies. Turning its back on his predecessor Hugo Chávez, Maduro moved towards eliminating price and currency exchange controls and imports tariffs, while allowing a de facto dollarization of the economy. Even the government’s relationship with the private sector became more amicable. “Venezuela is entering a cycle of economic liberalization,” a prominent businessmen affirmed, comparing the situation to 1980s China.

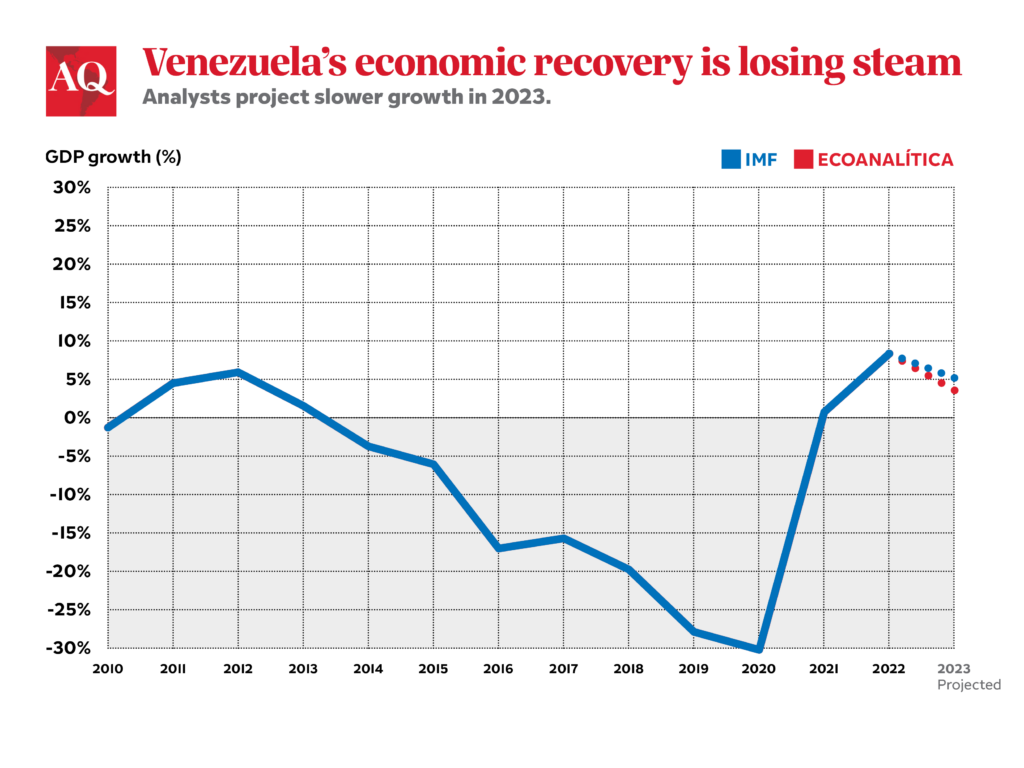

But without deep reforms, the mirage is vanishing. Economic consulting firm Ecoanalítica said consumption fell 18% in January compared to the same month in 2022. The economy contracted 8.3% during the first quarter of 2023, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Finances. By the end of 2023, Ecoanalítica expects GDP growth of 3.4%, a much slower rate than the almost 8% growth the firm estimated for 2022. “A relevant rebound effect is expected when you have such an important contraction,” Jesús Palacios Chacín, a senior economist at Ecoanalítica, said, “but the ceiling for growth is quite low.”

While the recovery benefited the goods and services economy, productive sectors like agriculture, industries and hydrocarbons need financing. Ecoanalítica estimates that the private sector needs around $6 billion in credit, but Venezuelan banks’ loan portfolio hover around $730 million. Similarly, the collapse of public services has reduced the competitiveness of companies by forcing the private sector to invest in electric generators, water wells and private transportation for its employees. Palacios Chacín also says a “deficient” legal framework—considering Venezuela’s recent history with expropriations and government interventions—keeps driving foreign investors away.

A new tax over transactions in dollars, enacted in April 2022, was followed by episodes of aggressive devaluation and inflation. The wages of private and public employees—60% were still paid in bolivars—plummeted. “They went from having a $170 monthly salary to gaining barely $80 or $85 per month,” Palacios Chacín said. According to Ecoanalítica, the percentage of Venezuelans with an income of less than $100 per month rose from 30% in July of 2022 to 52.6% this year.

Discontent is brewing

According to local pollster More Consulting, the percentage of Venezuelans who perceive their economic situation as better than the year before went from 52.2% in May 2022 to 28.3% in May 2023. The government has faced two waves of labor protests mostly led by public sector workers and teachers in less than a year. According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict, January 2023 saw a 136% increase in protests when compared to the previous January.

The expectations of an oil bonanza following the Ukraine War have also faltered. After the United States sent a delegation to discuss the restart of the flow of Venezuelan oil to the U.S., the Maduro government affirmed the country’s oil production would reach 2 billion barrels per day (bpd) by the end of 2022. By May of this year, oil production had barely surpassed 800.000 bpd according to official sources. And licenses given by the United States to companies like Chevron have proven to be quite restrictive, limiting payments to mostly oil-for-debt swaps or not allowing the exploitation of new wells.

According to Francisco Monaldi, a leading scholar on the economics of energy and a fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute, with these conditions the oil production would peak at 850.000 bpd. A production of 1 million bpd would need new licenses, which was conditioned to the election guarantees included in the halted Mexico negotiations between Chavismo and the opposition. While production rose from 2021 onwards, this was mostly pushed by the exploitation of Venezuela’s idle crude capacity, Monaldi explains. But the idle capacity is over, he says, unless PDVSA, the national oil company, manages to open new wells. But it currently has only two drills in operation, down from 120 in the late 1990s. (Also, only two of the country’s five oil refineries are partially operational, leading to gasoline shortages throughout the country and miles-long car queues to get fuel.)

Elections ahead

Venezuela seems to be cash-strapped, and the administration is cutting gasoline subsidies, firing doctors from public hospitals and teaching National Guards to bake and do hair styling as alternative means of income. Executives were purged from PDVSA along with the powerful oil minister after billions of dollars went missing due to the use of intermediaries to export its sanctioned oil (the billions lost could be equivalent to 27% of the GDP). The lack of cash could impact any distribution of favors ahead of the 2024 presidential elections, which will include the opposition for the first time in 10 years. “Public spending used to be 40% of GDP and its now less than 10%,” Palacios Chacín says.

The government remains highly unpopular and is trying to avoid any possibility of facing a united opposition front. Some candidates are banned from running and the Chavista-controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice recently took a case that could suspend the opposition’s primaries planned for October 22. This could trigger an internecine war between precandidates. Government-aligned figures threatened to ban the current leader in the polls, María Corina Machado, from running. And all Chavista-aligned members of the National Electoral Council (CNE) quit, ending any chance of technical assistance to the opposition’s primaries. “The government is not interested in the success of the primaries,” said Eugenio Martínez, a Venezuelan elections’ specialist.

Nevertheless, Martínez believes Maduro’s newfound pragmatism and desire to regain international legitimacy could lead to some concessions before the elections, despite the economic situation. “The nature of these concessions will depend on the capacity of the opposition to articulate and mobilize for 2024,” he said, “and the opposition should try to take advantage of even the most minimal concessions handed by Chavismo.”

This article was updated on June 27 to correct data on Venezuelan consumption.

—

Frangie-Mawad is a Caracas-based freelance journalist