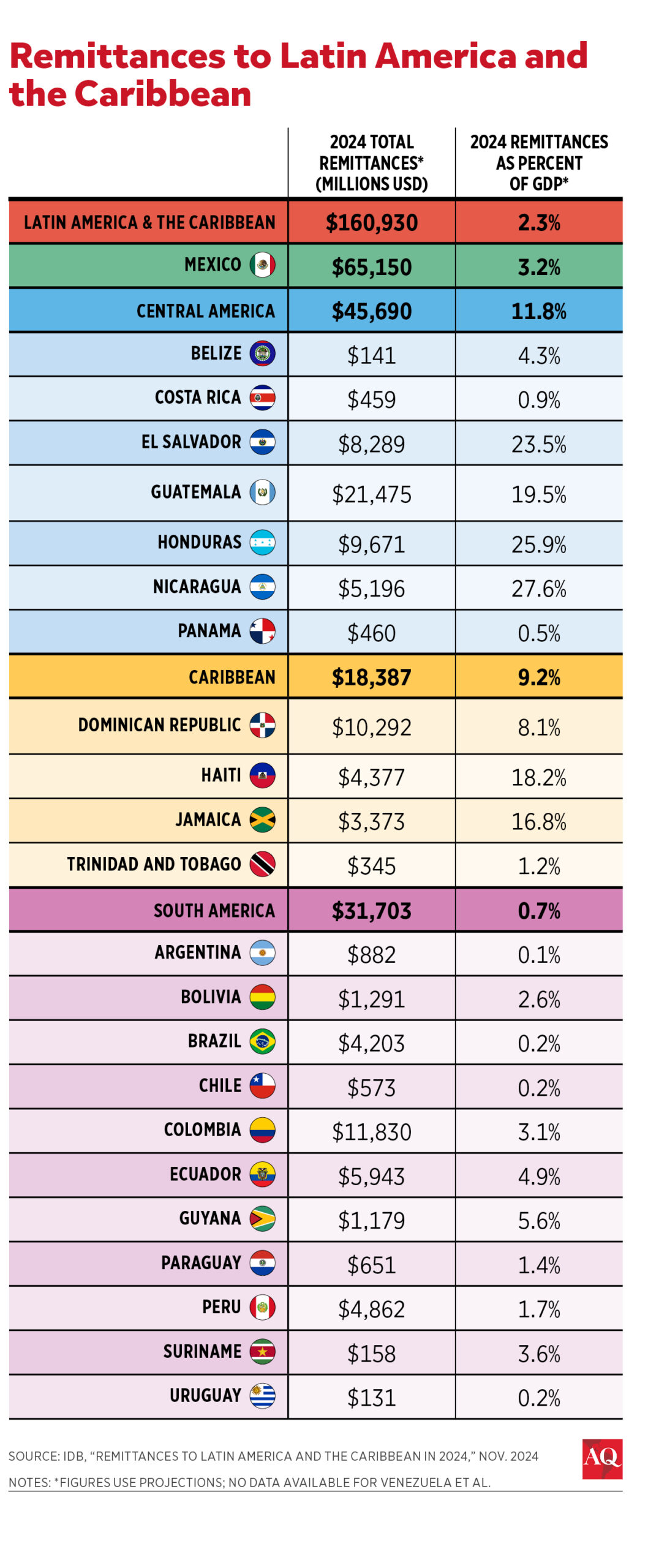

For decades, remittances have been a critical pillar of Latin American and Caribbean economies, representing a lifeline for the poorest families and a major boost for the region’s middle classes. A record $159 billion was received last year, up from $62 billion a decade ago. But now the landscape may change.

During his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump promised to deport millions of undocumented workers and restrict legal immigration to the U.S. to reset the nation’s migration policy, potentially reducing the number of senders and the amount of money flowing to the region. Meanwhile, proposals to tax remittances are gaining traction in Washington and some state legislatures. The combination of policies could significantly reduce the flow of remittances, undermining economic growth and potentially provoking instability in a region caught in a protracted low-growth trap, economists and analysts told AQ.

The effects would be felt most acutely in Mexico—which receives the highest volume of U.S. remittances at about $60 billion per year, equivalent to almost 4% of GDP—and the Central American and Caribbean countries where they are an especially vital economic engine: Nicaragua, which receives remittances equivalent to about 28% of GDP, Honduras (26%), El Salvador (24%), Guatemala (20%), Haiti (18%) and Jamaica (17%).

“In Mexico, the poorest households would be the most affected,” Sofía Ramírez, the director of México, ¿cómo vamos?, a Mexico City-based think tank monitoring socio-economic development, told AQ. Most remittances go to Mexico’s poorest states, and the bottom 30% of households receive over 65% of the total, according to government data. In Mexico—and across the region—the funds are spent primarily on household necessities like food, housing, and health care, boosting consumption and growth.

Ramírez noted that Mexican communities with the highest migration rates, and therefore the most experience reaching the U.S., would be hardest hit by any reduction, potentially driving more people to attempt the journey north.

In Central America, the fallout could go beyond the real economy to cause balance-of-payment and exchange rate instability, said Ricardo Barrientos, director of the Central American Institution for Fiscal Studies (ICEFI). This would hobble growth and job creation, Barrientos told AQ. “In Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador at least, any drop in remittances would likely hurt the economy in multiple ways, creating conditions likely to further encourage migration,” he said.

The deportation threat

Trump team’s statements imply that the number of people deported to Central America could be historic. Vice President-elect J.D. Vance recently called deporting 1 million people per year a “reasonable” target, and while it’s unclear how many of those will be from Central America, almost 20% of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. are from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Even a “very conservative scenario” in which additional taxes are not imposed, and the Trump administration deports only around 70,000 people from these four countries annually, would create a “serious economic growth problem that could have recessionary effects” within four years, Manuel Orozco, the director of the Migration, Remittances and Development Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, a think tank in Washington, DC, told AQ.

In his first term, Trump deported around 1.5 million people, about the same number as Biden and fewer people than Obama did during his first (2.9 million) and second term (1.9 million). Under each of these presidents, remittances grew steadily—over the course of Trump’s first term, remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean rose from around $80 billion to $100 billion. This time around, however, Trump has promised “the largest deportation operation in American history” and recently confirmed his plan to declare a state of emergency to enlist the U.S. military in mass deportation operations.

New tax plans

Meanwhile, proposals to tax remittances from the U.S., estimated at an annual $80–150 billion, are also gaining momentum. In his first term, Trump considered such a tax to pay for border wall construction but ultimately withdrew funds from elsewhere. Now, his Vice President-elect, J.D. Vance, has a bill before Congress that would impose a 10% tax on remittances and use the revenue to harden the U.S.-Mexico border.

Several U.S. states are also considering their own taxes. Oklahoma already has a law that imposes a $5 tax on remittances under $500 and a 1% tax on all transfers above $500. Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania are reviewing similar proposals, while Arizona is deliberating a tax as high as 30%. These levies would be in addition to fees that generally take an average of around 6% out of remittances to Latin America.

Vance has said his proposal, the Withholding Illegal Revenue Entering Drug Markets (WIRED) Act, is meant to dissuade illegal immigration and reduce cartel revenue. Proponents of such measures say recipients too often use the money to pay for their unlawful migration, lining the pockets of smugglers and the organized crime groups they work for.

Moreover, they say, the taxes will reduce revenues for Mexican organized crime groups known to launder profits made in the U.S. by disguising them as remittances. However, experts like Orozco say the vast majority of remittances are almost certainly legitimate. Other bills before the U.S. Congress also seek to address laundering with increased monitoring and prosecution, as opposed to taxation.

Effects on stability

To assess their potential impact on regional stability, such proposals must be considered in the context of other moves the Trump administration is likely to make, said Emily Mendrala, a senior advisor to Dinámica Americas who was formerly senior advisor on migration to President Biden and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for the Western Hemisphere. “I don’t know that the tax on remittances in isolation would cause hugely destabilizing impacts,” she said, “but taken as a whole, all these policies together could.”

She cited plans for mass deportations of unauthorized workers and possibly revoking temporary legal status—such as Temporary Protected Status (TPS), DACA, and humanitarian parole—for migrants in the U.S., including approximately 1.8 million people from Latin America and the Caribbean. “If you see, for example, TPS revoked for Salvadorans, Nicaraguans and Hondurans … reintegrating them into society would be hugely resource-intensive,” Mendrala told AQ. “If not done well, the impact could be destabilizing; it could drain resources and cause social strife.” TPS eligibility is set to expire for about 184,000 Salvadorans in March and 55,000 Hondurans and 3,000 Nicaraguans in July.

In Mexico—where remittances provide more foreign income than almost any other sector, including tourism, oil exports, and most manufacturing—deportations and stricter border enforcement would likely dent the flows more than the taxes, Ramírez, the director of México, ¿cómo vamos?, said. “Even if there’s a tax, people will send remittances. But if there are fewer people sending them, that will have a greater impact,” she added.

To compensate for the implementation of a potential tax, Mexican workers in the U.S. may even send more money. During the COVID-19 pandemic, despite unprecedented disruptions, remittances to Mexico defied expectations, rising about 11% in 2020 and another 27% in 2021 to $52 billion. “Even during the pandemic, we kept seeing more of the same,” Ramírez told AQ.