QUITO – Last month, Ecuador’s President Guillermo Lasso made something of a splash at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, fervently defending internationalism and open, democratic governance at a time when closed, nationalistic politics have gained ground around the globe. But just weeks later, the Pandora Papers leaks threatened to dent Lasso’s reputation with evidence of his offshore transactions. Lasso maintains these ended after the passage of a 2017 Ecuadorian law restricting politicians’ use of offshore accounts. After a period of highs and lows, where does he stand now?

Lasso’s election in April as Ecuador’s first center-right president in over 20 years broke a longstanding and tumultuous cycle of left and right-wing populist leaders. Many observers, myself included, were skeptical about his chances for victory for a number of reasons. Anti-elite sentiment in Ecuador, lately exacerbated by a surge in inequality, sits uneasily with Lasso’s past as a prominent banker and his neoliberal economic beliefs — his recently released government plan quotes from Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman. Even in many staunchly capitalist countries, Lasso might be expected to face resistance over these issues in the wake of the pandemic. But especially so in Ecuador, which was an outlier in the region for resisting the neoliberal wave of the 1990s. Finally, his social conservatism (Lasso personally opposes abortion even in cases of rape) is becoming outdated in a country where liberal social ideas are finally gaining some traction.

Nonetheless, after losing presidential elections in 2013 and 2017, Lasso’s third time seeking the office was the charm. His victory delighted local and international investors, as indicated by a significant fall in Ecuador’s country risk following the election. Country risk has remained at a lower level since, thanks to several reassuring steps taken by the government. Lasso appointed a technocratic cabinet close to the business community, facilitating regular dialogue between government and the private sector. He has presented a government plan centered on reducing state intervention, opening several industries and markets to competition, and promoting public-private partnerships. He has engaged the international community pragmatically, reaching out to governments from China and Russia to the U.S. on issues ranging from vaccines to trade, and has achieved important victories, such as a successfully renegotiated, more flexible agreement with the IMF. Investors are now looking at Ecuador with renewed interest, especially in contrast to growing upheaval in other traditionally more business-friendly Andean countries.

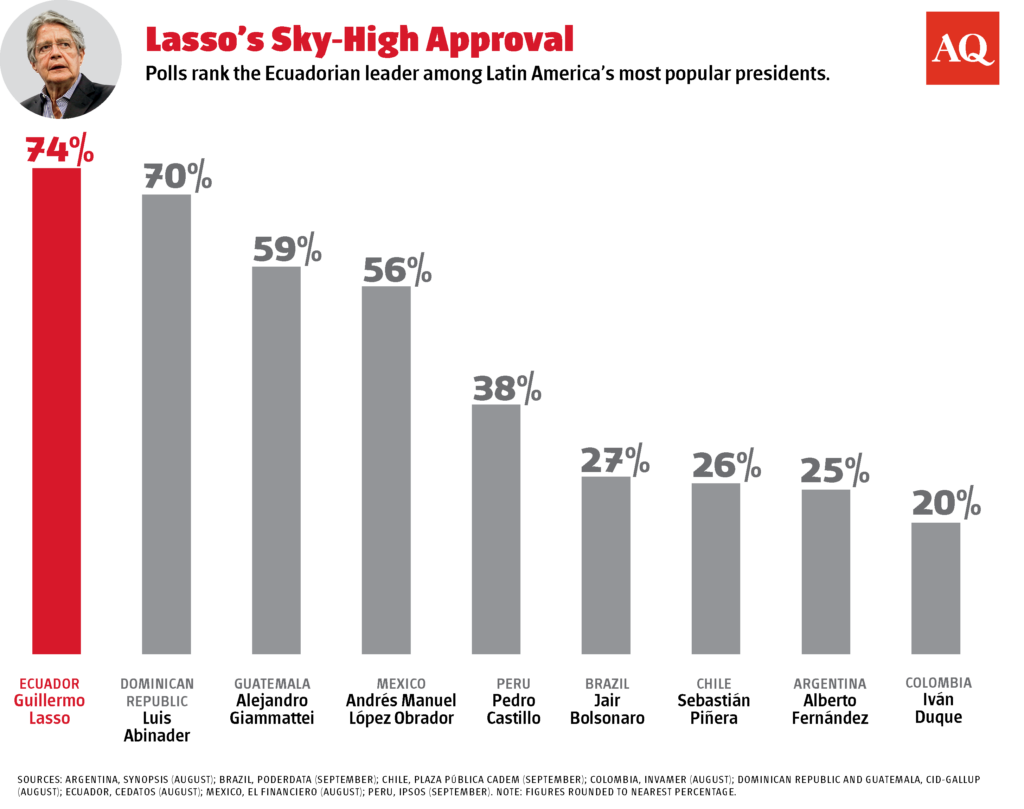

So far, Lasso has walked a tightrope, taking steps to improve the business climate without alienating Ecuador’s centrist and left-leaning majority. His popularity has surged beyond his traditional political base thanks to an extremely successful vaccination rollout, which immunized over half of the population of 17 million in 100 days. Benefiting him, too: an economic rebound following the lifting of domestic COVID-19 restrictions, and his calls to reform discredited political institutions. The result? Lasso currently enjoys a sky-high 70% approval rate according to several local polls.

Nonetheless, Lasso’s first real test still awaits him. His administration’s first months were always expected to be a political honeymoon, especially after the far less competent government of Lenín Moreno. The Ecuadorian central bank still only expects 3% growth this year, after an 8% contraction in 2020 increased poverty levels. Two-thirds of workers are underemployed, crime is rising and there has been a large spike in illegal migration to the U.S.

Ecuadorians have high expectations that the Lasso administration can reverse the decline in living standards during the pandemic and years of economic stagnation beforehand, during Moreno’s presidency and the latter years of his predecessor Rafael Correa. However, Lasso’s remedy for Ecuador’s economic malaise — namely, liberalizing reforms — face significant political opposition both in a Congress dominated by the left, as well as among civil-society groups such as the indigenous movement, if not the population as a whole, even including those who ended up voting for the former banker.

Lasso’s agenda for economic reform, key to his plan to transform the country, is yet to be debated in Congress. When the executive branch recently submitted a tax, labor and investment “mega-law” to the legislature, it was rejected outright before even reaching the floor. While the legislature could still pass a diluted version of Lasso’s tax reforms, which target top earners, more significant changes to make rules more flexible for hiring and extractive sectors face an uphill battle.

This has led the Lasso administration to consider alternatives — going directly to the people with reforms on a multiple-question referendum, for example, or calling for new presidential and legislative elections in the hope he will be reelected along with a larger delegation in Congress. Nevertheless, there are no guarantees that the public will back such moves, especially considering that Lasso still hasn’t built a clear political narrative around what his proposed transformation means for most Ecuadorians. The public, now vaccinated, is turning its attention to other pressing social problems. What’s more, recent events, such as a deadly jail massacre in Ecuador’s largest prison and an investigation by the legislature into Lasso’s offshore transactions, have somewhat weakened the government’s reputation for competency and its reformist credentials. The magnitude of the challenge that he faces to transform Ecuador is hard to understate. Nonetheless, Lasso has already pulled a few surprises out of the bag. Let’s see if he can do it again.

—

Hurtado is the president and founder of Quito-based political risk consulting firm PRoFITAS