This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala.

On April 1, 1927, in the Mexican city of Guadalajara, a 38-year-old man was seized by government forces and subjected to unspeakable forms of torture.

When he refused to talk, he was hung by his thumbs. The soles of his feet were slashed. Finally, he was executed by firing squad. His name was Anacleto González Flores, and he was a Catholic lawyer and leading member of the Association of Mexican Catholic Youth (ACJM). A law-abiding citizen for most of his life, he was targeted by Mexican authorities because he had begun urging Catholics to take up arms against the government.

González Flores was one of thousands of Mexican Catholics who supported an armed rebellion against the Mexican government’s anticlerical reforms in the mid-1920s. The ensuing wave of violent clashes between Catholics and the state would reverberate through Mexican politics for decades—and the way the conflict was finally resolved may still be influencing Mexico’s left today.

In 1926, the anticlerical President Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–28) had passed a new penal code that took direct aim at the power and influence of the Church and its clergy. Those reforms had their roots in the 1910 Mexican Revolution and were the latest chapter in a century-long saga of tense relations between the Catholic Church and the state in Mexico.

Brought to Mexico with the Spanish conquistadors, the Catholic Church had been a dominant force in the country since colonial times. Calles and his allies, loyal to the values of the Mexican Revolution—reason, secularism, and socialism—were convinced that the Catholic Church was an impediment to modernization and progress.

But most Mexicans remained Catholic—and the country contained a powerful organizational network backing up the Church. Catholic organizations like Anacleto González Flores’s ACJM helped to organize passive resistance to the federal government, such as protests and boycotts. But this failed to persuade the government to alter course—and so Mexico’s Catholic clergy took the drastic action of shuttering churches across the country and suspending the administration of the sacraments.

Devout Catholics across Mexico were furious at the sudden withdrawal of Catholic rites, and resented the government’s overtly anti-religious policies, including a “de-fanaticism” campaign aimed at freeing Mexicans from the grip of religious ignorance. Churches were turned into stables for animals. In Tabasco, the home state of future President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018-24), the governor organized public bonfires of crucifixes and statues of saints and the Virgin Mary. With Calles and his anti-Catholic policy’s tight control over the federal government, religious freedom was under assault across the country. Thousands of Catholics responded by taking up arms, forming militias, and launching direct attacks on the state, starting in August 1926. The uprising was particularly strong in Mexico’s west-central states, including Jalisco, Michoacán, and Guanajuato.

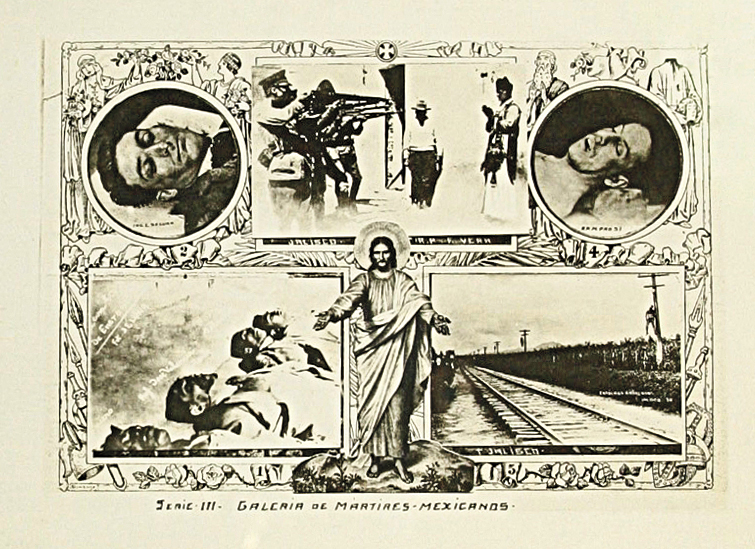

(Photo courtesy of cehm.org.mx)

Rebels and martyrs

In the war that resulted, tens of thousands of Catholic soldiers fought bloody guerilla battles against federal forces, unleashing a wave of violence across the Mexican heartland. They were known as “Cristeros,” for their battle cry ¡Viva Cristo Rey! (“Long Live Christ the King!”). Many in the Cristeros’ rank and file were peasants, but others—including the leaders of Catholic organizations like the ACJM—were middle-class urban Catholics, particularly in Guadalajara and Mexico City. Women also participated in the conflict, mostly as spies and arms smugglers. The majority of priests did not take up arms, although there were some notable exceptions, like Father José Reyes Vega, who became a general in the Cristero army.

The Cristero War produced a generation of martyrs: Catholics who were killed in defense of their faith. Those who died without taking up arms, like Anacleto González Flores, were subsequently declared “blessed” by the Catholic Church, and 25 men and boys were eventually canonized as martyrs. One of these was José Luis Sánchez del Río, a 14-year-old Cristero flagbearer who was captured and endured horrific torture, but refused to renounce his faith and was executed in front of his horrified parents.

The Cristeros were highly aware of the sympathy that their suffering would generate in the broader Catholic world, and they produced and circulated vivid images of martyrs and martyrdom in photographs and postcards that were shared widely beyond Mexico’s borders. In the United States, the Knights of Columbus, a lay Catholic men’s organization, was appalled by the violence against Mexican Catholics and launched a publicity campaign to make U.S. Catholics aware of the martyrs. Catholics across Europe, too, rallied and wrote in support of the Cristeros.

Bloody resistance

Mexican Catholics were not mere victims in the conflict: Many committed violence in the name of their faith. Much of this violence was directed at federal troops— but some Cristeros attacked civilians as well. Father Vega, the militant priest, organized a brutal and shocking ambush on a passenger train in April 1927, in which dozens of passengers were shot and burned alive.

The conflict’s exact toll will never be known, but historian Jean Meyer has estimated the casualties at 90,000. The war also fueled a wave of emigration and exile from the rebellion-torn region to other regions of Mexico and to the United States.

In part because of the violence and chaos unleashed by the war, the Mexican clergy—backed by American priests and the Vatican—became eager to negotiate peace with the Mexican government. After a series of meetings between high-ranking clerics, representatives of the U.S. Church, and Mexican political figures, the Church and state came to an agreement that restored some rights to clergy, returned church properties, and reopened churches. In exchange, the Cristeros laid down their arms on June 21, 1929.

Photo by Ullstein Bild/Getty

An imperfect peace

But the peace that resulted was unstable. The rebels and their supporters felt betrayed by their own religious leaders, as they continued to experience harassment and religious persecution. As early as 1930, some former Cristeros began to regroup and to organize more sporadic and targeted resistance, particularly against teachers and peasants who supported the revolutionary government.

By the mid-1930s, a second Cristero uprising had materialized—in response to a new model of socialist and secular public education promoted by Calles and implemented under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas. The program was explicitly designed to liberate Mexicans from the alleged ignorance generated by religious beliefs. Its overtly anti-religious and socialist content reinvigorated the Cristero cause—and socialist teachers were targets, seen as embodiments of the assault upon religious freedom.

From 1934 to 1940, hundreds of Cristeros orchestrated attacks against socialist teachers and peasants. Less widespread, without support from the Catholic Church itself, the new wave of resistance still threatened the legitimacy of the revolutionary government. Catholic vigilantes and mobs used brutal violence against socialist teachers, including rape, mutilation and hanging. Severing ears was so pervasive that one famous Catholic vigilante, Odilón Vega, was known as the desorejador de maestros (the “de-earer of teachers”). Historians David Raby and Jean Meyer say that at least 100 teachers were assaulted or killed.

Cárdenas’ influential pivot

Facing another Catholic uprising, Cárdenas sought to distance himself from his predecessor’s anticlericalism, pivoting toward a more conciliatory approach to the Church.

His reasons may not have been exclusively political: A childhood friend of Cárdenas was Luis María Martínez, who would become archbishop of Mexico in 1937. Cárdenas eventually abandoned socialist education and attacks on popular religion, pushing out anticlerical leaders and repealing Calles’ anticlerical penal codes in 1938. Instead, he focused on economic issues: land redistribution, the modernization of the countryside, and the policy for which his government would be most remembered, the expropriation of U.S. and U.K. oil companies. Today, Cárdenas is widely revered across Mexico, portrayed as a humble reformer who brought the promises of the Mexican Revolution to the common people, offering them land and welfare support.

Over the following decades, as anti-communism swept much of the world during the Cold War, Mexican leaders moved into greater collaboration with the Catholic Church. Famously, as president-elect, Manuel Ávila Camacho declared in 1940, “I am a believer,” and subsequent leaders would be careful not to alienate Catholic voters. That kind of improved Church-state relationship is hard to imagine without the pragmatic policies of Lázaro Cárdenas.

Image from Fotografías del Mundo Cristero, Fondo y Clasificación/CEHM

The Cristero uprising’s legacy today

Today, Catholicism remains a powerful force in Mexico, where government figures show 78% of the population are adherents— higher than the Latin American average of 54%, according to pollster Latinobarómetro. Some politicians on Mexico’s far-right have recently sought to use Catholicism to rally opposition against the country’s ruling Morena party, harking back to the Cristero uprising. Eduardo Verástegui, a telenovela star turned pro-Trump defender of faith and family, made a bid to run in last year’s presidential election, comparing AMLO with Calles and characterizing his government as socialist and impious.

But Verástegui’s bid fizzled after he fell far short in his effort to gather enough signatures for a spot on the ballot as an independent. What explains the failure of a Catholic politics in a still-Catholic country? A large part of the answer may be that AMLO—a lover of history himself—has drawn lessons from the pragmatism of Lázaro Cárdenas, one of his great heroes.

Although AMLO presented himself as a leftist, he also defended conservative cultural values centered on the family, and didn’t shy away from expressing his Christian faith. That drew criticism from some feminists during his administration—criticism he often dismissed as coming from a “spoiled” false progressivism.

AMLO’s embrace of family and faith seems to have paid dividends in impeding the growth of a religious right to oppose his dominant Morena party, now overseen by his successor in the presidency, Claudia Sheinbaum. Indeed, the name of their political party, Morena, evokes the Virgin of Guadalupe (often referred to as the Virgen morena or brown Virgin). He famously wore Catholic scapulars to ward off coronavirus—gestures that served him well amongst a Mexican public that is still predominantly Catholic.

As we approach the Cristero Rebellion’s centennial in 2026, we will likely see more attempts to equate Morena with the socialism and anti-clericalism of the 1920s and ’30s, and appeals to the memory of the Cristero conflict to mobilize Catholics in opposition.

Yet if the history of this conflict can teach us something, it is that Mexican political leaders have learned to recognize the importance of religion for the Mexican people—and that they can advance socialist and leftist ideas without reviving the anticlerical campaigns of the past. Indeed, they can do so even while invoking the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, or traditional Catholic values. So long as leftist politicians continue to walk that line, they will avoid provoking painful memories of the Church-state conflict that roiled Mexico almost a century ago.