This article has been updated

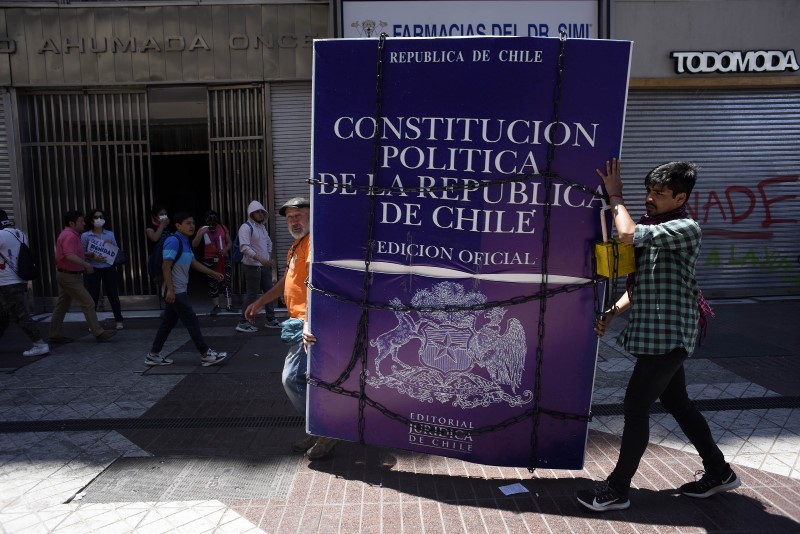

SANTIAGO – The world may have been taken by surprise by the social and political crisis that began in Chile on Oct. 18. But the demand for a new social contract at the center of the protests is nothing new.

In the run-up to Chile’s 2013 presidential election, a campaign dubbed “Mark Your Vote,” which encouraged Chileans to scribble their ballots with the letters “AC” (for constitutional assembly), had already sent a clear message. In the first round of that election almost 8% of votes nationwide were marked AC, as were over 10% in the runoff round that elected Michelle Bachelet. In response, five days before the end of her administration Bachelet sent Congress a bill that could have opened the way for a new constitution. It was never taken up for discussion.

Fast forward to 2019 when on Nov. 15, after more than four weeks of protests, almost all of Chile’s major political parties agreed to call a referendum on a new constitution. In April 2020, voters will decide on the need for a new document and the nature of the body that would be tasked with writing it. The accord also defined that any decision made by the selected body would need to be approved by a two-thirds majority.

According to one poll, 78% of Chileans agree that the country needs a new constitution. Among those who support the writing of a new document, several polls conducted over the last few weeks have shown high levels of approval for a new constitution through the election of a constituent assembly, which would comprise only members elected specifically to write the constitution and leave out current members of Congress. The launch of a process to change the constitution – along with a short-term agenda for social and human rights and the fight against corruption – could defuse the current social and political crisis.

Chile’s current constitution was adopted in 1980 by the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and ratified through a constitutional referendum under questionable circumstances, due to a lack of voter registrations and the prevailing restrictions on freedoms. The constitution was based on a bill drafted over five years by a so-called “Studies Commission” formed by eight people appointed by — and serving at the pleasure of — the ruling junta. The junta itself revised the final draft, which enshrined several authoritarian provisions such as life-long senatorial appointments, permanent tenure of military chiefs and the extension of Pinochet’s term for eight more years.

The constitution has since undergone several changes. In 2005 a major reform was signed by then-President Ricardo Lagos, who proclaimed that Chile “finally had a democratic constitution.” Some of the authoritarian aspects mentioned above were removed, and in both political circles and academia various groups viewed it as a profound reform that had successfully transformed Chile from a dictatorship to a democracy in a peaceful manner.

What next?

Doubts continue over whether the latest agreement between the government and the opposition will have an impact on the protests. Many questions remain, such as what will happen to constitutional reforms that do not pass by the required two-thirds majority. Will voter referendums be held for citizens to decide on hung issues? Meanwhile, distrust in political parties and Congress continue to prevail and several groups question the agreement’s legitimacy altogether.

Undoubtedly, the most difficult part of the current process will be to channel citizen demands into the conversation without leaving the political establishment behind. Despite the general repudiation they receive, organized parties are essential for democracy in Chile. In the same fashion, the country needs to shed fears and create a political solution that draws upon lessons from other countries – adapted to its own reality – and provide guarantees that no group will be excluded.

Some sectors of society still distrust the idea of a constitutional convention, due in part to the recent experiences in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. Chile will require a concerted effort from political institutions and civil society to keep citizens informed about the process and avoid falling into fear campaigns. The process must be as transparent, participatory and inclusive as possible.

Chileans won’t all be 100% happy with the result. Our great challenge is to form a new social contract through consensus, taking into account both the progress we have achieved with our young democracy, and its demands for greater social justice and equality.

This article was updated to clarify Chileans’ level of support for aspects of a new constitution

—

Jaraquemada is advocacy director at Espacio Público