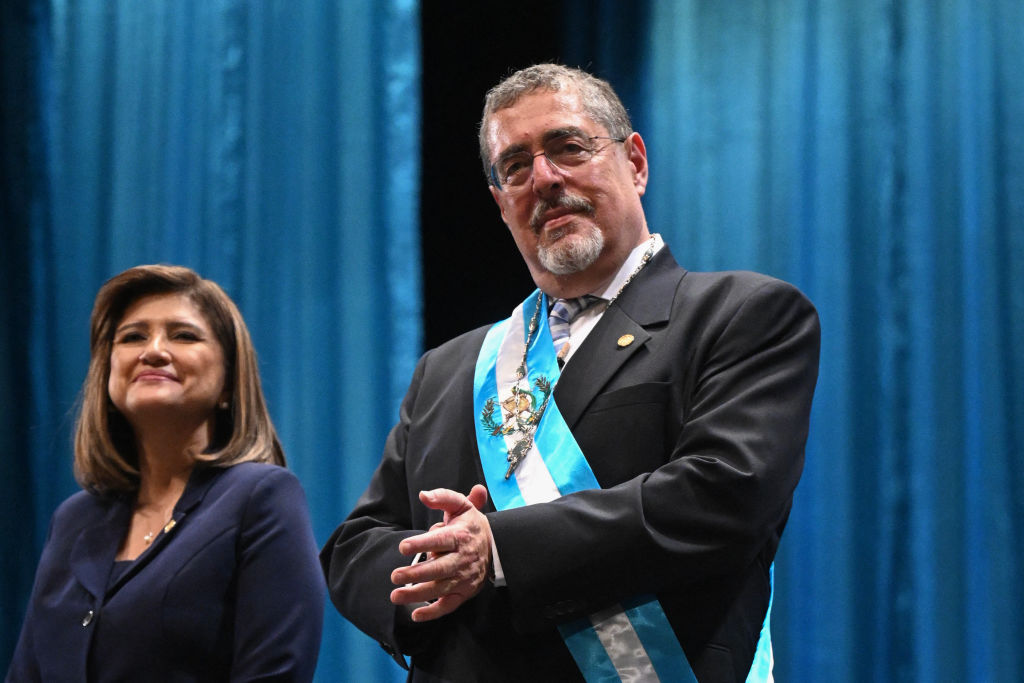

GUATEMALA CITY — President Bernardo Arévalo was inaugurated past midnight on January 15 after a series of chaotic delays. His opponents in Congress tried to buy time to keep control of the chamber’s leadership committee, but after hours of drama, Arévalo’s Semilla party emerged at the head of a majority coalition. This tumultuous start to Arévalo’s term signals the challenges ahead for his ambitious anti-corruption agenda through a year likely to be just as turbulent as the last.

There will be opportunities, but with the feeling that trap doors lie around every corner. In the week before the inauguration, a Constitutional Court judge asked for protection from death threats. A court ruled that four Supreme Elections Tribunal judges should be detained. A former interior minister was taken from his home by police and from jail he said it was because he refused to fire on October’s massive protests in support of a democratic transition.

“We will not allow our institutions to be overcome again by corruption and impunity,” Arévalo said in his inaugural speech. “We now have a historic opportunity to reverse decades of state neglect and institutional deterioration.”

This will be no easy task. Years of corruption have rotted the country’s institutions from within, said Alexander Aizenstatd, a constitutional lawyer in Guatemala City. “Not only do they not serve their proper functions, they actively violate people’s rights,” he said.

But Arévalo and his party are determined to strike at the roots of this degradation. The opposition to Arévalo was so intense because he promised to continue the unfinished business of the CICIG anti-corruption commission, shuttered after it revealed graft at a massive scale, implicating everyone from politicians and business elites to unions to religious and university leaders.

The corruption networks that managed to oust the CICIG in 2019 have been metastasizing for decades and seemed firmly in control of the 2023 elections. They disqualified the “change” candidates who polled as threats and jailed or forced into exile dozens of journalists and anti-corruption prosecutors and judges. But they left Arévalo alone because he never registered above 2% before the first-round election. As the authorities’ grip on power seemed tighter than ever, the change vote had silently coalesced around him.

How Arévalo made it to the presidency despite the obstacles—through a combination of massive demonstrations led by Indigenous organizations, international pressure, and his own calm and conciliatory style that seeks accord over conflict—offers cause for optimism. Meanwhile, Semilla’s successful vote in Congress realigned the legislature, fracturing the two major traditionalist parties and offering hope that it may cooperate with Arévalo.

This dramatic realignment means that Semilla’s legislative agenda may stand a chance, said Inés Castillo, a three-term member of Congress expelled from the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE) party last week for breaking ranks. “UNE, Vamos, all these parties have acted according to electoral financing from the powerful groups who do business with the state … Today, Guatemala has an opportunity to effect a legislative agenda through legislators who are more independent,” he told ConCriterio. “This is historic.”

The year ahead

Beyond Semilla’s immediate legislative agenda—focused on laws to regulate the use of the nation’s water, break up monopolies, and lower drug prices—Arévalo’s ability to effect structural change will hinge on three key fronts: reforms of the government contracting system at the heart of a slew of corruption scandals; the recovery of the Attorney General’s Office; and nominations to the high courts.

Contracting reforms may offer Arévalo the best chance to deliver concrete quality-of-life improvements. If he manages to make spending more transparent and more efficient, especially on infrastructure and health, the public will see better roads and more medicines on hospital shelves before the year is out. Greater private investment may also pour into the country.

The other two fronts are thornier. The Attorney General’s Office is controlled by Consuelo Porras, sanctioned by the U.S. for “significant corruption.” (She denies wrongdoing.) Her second tenure as Attorney General (2022-26) has produced a stream of decisions that have undermined anti-corruption investigations. Guatemala’s Odebrecht prosecutions are a case study of impunity; the prosecutors who sent corrupt officials to jail were themselves imprisoned or forced to leave the country.

Arévalo does not have the constitutional authority to remove her but insists he will ask her to resign immediately. He may succeed by starving her of resources. If she does resign, Arévalo will likely have to pick her replacement from the other five candidates approved by a commission in 2022, a list that includes relatively clean choices.

Meanwhile, the court system is scheduled for major changes in 2024, on the order of 250 new judicial appointments, including all 13 Supreme Court seats. This is a major opportunity for reform, but nominations come from the National Lawyers’ Guild, itself beset by corruption allegations, and must go through Congress.

Arévalo’s key challenge

This battle will be slow, and its outcome will be determined by whether Arévalo can defuse tensions within his diverse social and congressional coalitions. This will be his most important challenge. Private sector leaders and grassroots Indigenous organizations have very different visions of what development should look like, and this is just one of many precarious fault lines.

But the good news is that Arévalo inherits an economy that reliably grows over 3% a year and that the public—well aware of the obstacles he faces due to the spectacular nature of the last six months—is likely to forgive slow progress as long as it’s in the right direction. He has also moderated his economic proposals and included representatives of powerful private sector lobbies in his Cabinet to maintain a positive relationship with them.

The uniqueness of the moment seems to point in Arévalo’s favor. Guatemala’s voters, genuinely heartsick at a status quo that maintains most of the country in poverty, demanded a major disruption. But their disruption was a democratic and peaceful one that handed the presidency not to an autocrat or a populist, as so many other heartsick people have done, but to a radical conciliator with a reputation for being reasonable.

This will make it especially difficult for Arévalo’s antagonists to mobilize opposition. Even so, the coming year is likely to be, as were the last six months, a week-by-week struggle.