This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the 2024 U.S. presidential election and its impact on Latin America

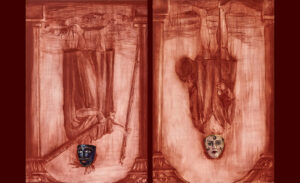

Earth caked onto cotton paper, industrial waste and gold dust layered in violent strokes and thin lines. In her latest exhibition, Layú biza’bi, the Oaxacan artist Dell Alvarado creates a visceral testimony to a territory singled out for development promotion by Mexico’s outgoing president—but riven by the environmental toll of resource extraction.

In collages, sketches and sculptures, Alvarado draws on her own extensive travel through the mountains, valleys and mangroves of her native community in Oaxaca. Alvarado hails from Guidxi Gubiña, the term in Diidxazá, a local language, for a town of 14,500 in Oaxaca officially known as Unión Hidalgo. It’s one of many binnizá communities, a subgroup of the Zapotec peoples, on the Pacific coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

All photos from a previous exhibition at El Alacrán in Oaxaca de Juárez, courtesy of Dell Alvarado, Dani Joss and Adriana Monterrubio.

The isthmus has undergone a radical transformation over the last several decades. In 1994, the state-owned CFE utility started a trend of building wind farms in the area; in 2008, Spanish company Iberdrola built Mexico’s first private wind farm nearby. Now there are more than 2,000 turbines in the region. As one of the shortest land routes between the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, the isthmus is also being promoted as an alternative commercial route to the Panama Canal. Through the Interoceanic Corridor (CIIT) megaproject, the Mexican government has invested in a network of industrial parks, railroads and ports meant to propel development in the region.

But development in practice, as Alvarado sees it, means barbed wire, armed patrols, deforestation and pollution caused by lubrication oils leaking from wind turbines. In Guidxi Gubiña, the town’s fresh water has become polluted and the electricity is cut off frequently despite massive energy production nearby. Communal ejido farms have been fenced off, and illegal mining lurks at the edges of the territory.

Layú bisa’bi (The Promised Land)

Casa Guietiqui in Santo Domingo Tehuantepec

by Dell Alvarado

On view through July 29

Layú biza’bi challenges its audience to engage with a series of labels, translations and maps relating to the local impact of resource extraction. In a corner of the gallery, a desk is set up with research notes highlighting important data, like the depth of holes dug to support wind turbines.

This combination of hard data and raw emotion is meant to spark conversations about taboos within Alvarado’s own community. Guidxi Gubiña was founded after the Mexican government burned down binnizá villages and forced inhabitants into one town. This violent origin produced fractures that have only deepened with the intensification of resource extraction.

Searching for an artistic medium beyond the traditional decorative arts often sought after by tourists, Alvarado left her hometown to study art in Oaxaca’s capital. Now she’s found a way of exploring social change in the isthmus through an investigative art practice. Layú biza’bi has offered Alvarado an opportunity to deepen her intimacy with her territory through two years of artistic fieldwork. That intimacy bears very tangible fruit in the earth pigments that Alvarado employs in her art—a series of paints that she produced herself from soil she collected. Evoking a primordial impulse to reach out and touch the bare earth, the pigments showcase the soil’s unique color palette: rusty reds, burnt browns and yellows.

Speaking out in Oaxaca carries heavy risks—dozens of environmental advocates are murdered in the region every year. In spite of the danger, Alvarado chooses to suspend from the ceiling a piece of dirty industrial fabric in the middle of her exhibition. Evidence of turbine oil spills on Gubiña land, it’s also a testimony to the artist’s resolve to concretely express the traumatic realities afflicting her community.

—

Villa Franco is a writer from Bogotá and a research fellow at the Human Rights Foundation