This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on A (Relatively) Bullish Case for Latin America

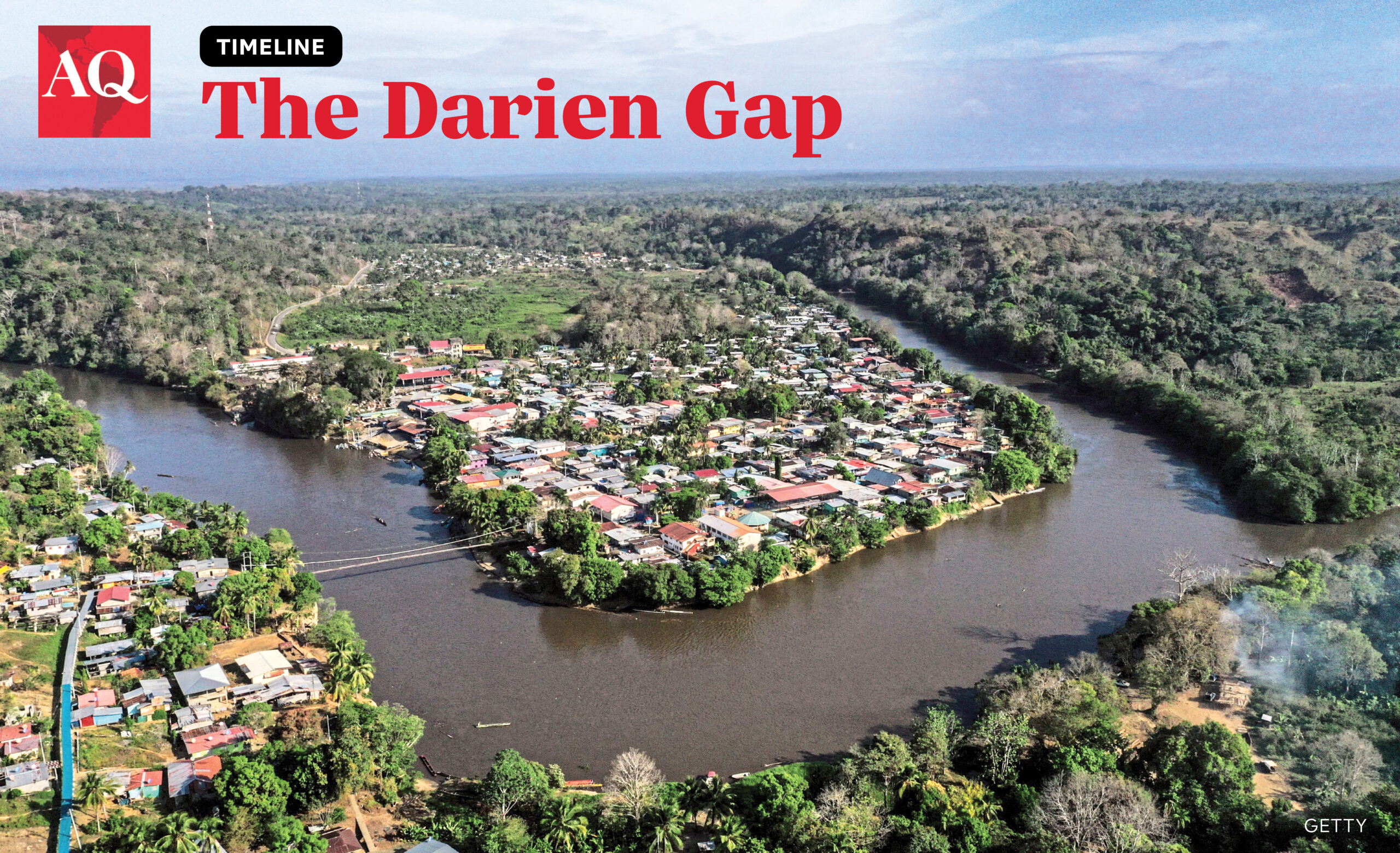

In the cemetery of El Real de Santa María, a village accessible only by river in eastern Panama, stands a new mausoleum. Donated by the Red Cross in March 2023, the modest concrete structure contains a grid of 100 niches for human remains. Since 2021, over 130 migrants have died crossing the Darién Gap, 575,000 hectares of jungle where the Central American isthmus connects with Colombia—mainly from drowning, falls and acts of violence. For the dozens of bodies that cannot be identified, the mausoleum will become their final desolate resting place.

For five centuries, the Darién Gap has possessed a fearsome reputation as a uniquely inhospitable terrain and has accrued a litany of lonely deaths. Local legend has it that the final act of a Spanish conquistador, whose body was found floating in the Pacific waters of the Darién, was to inscribe in rock the phrase Panamanians most associate with the region: “When you go to Darién, entrust yourself to Mary, for in her hands is the entrance and in God’s the exit.” By the early 2000s Lonely Planet’s advice for backpackers eyeing up the trek to Colombia was more succinct but essentially unchanged: “Don’t even think about it!”

Despite these and other warnings, today the Darién is one of the most well-trodden migration routes in the world. While media reports of the Darién’s humanitarian crisis describe a “no-man’s-land” of hellish conditions, impenetrable jungle and deadly wildlife, in 2023 an estimated 400,000 migrants are expected to cross on foot northwards over a number of routes, some of which have come to resemble muddy highways. In August alone 58,000 made the crossing, a record. Colombia and Panama are the only countries in the Americas that share a land border but are not linked by even a rudimentary road.

That the Darién is the only land route between two continents makes the persistence of this blank space on the map an even more curious anomaly of human geography. Over the course of its history, numerous attempts have been made to take advantage of the Darién’s strategic position—some more serious than others—but all have been thwarted by nature or politics.

Beachhead of colonization

In the early 16th century, the Darién’s prospects looked different. Founded by conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1510 on Caribbean shores close to the entrance to the Gulf of Urabá, the town of Santa María la Antigua del Darién was one of the first European settlements on mainland America. “The history of Spanish colonialism in Latin America began in the Darién,” said Hernán Araúz, a historian and veteran guide of eight trans-Darién expeditions. “Santa María la Antigua served as a jungle training school for the conquistadores.”

In September 1513 Balboa led an expedition through the jungles and mountains of the Darién, becoming the first known European to reach the American shores of the Pacific. The Indigenous Cueva people’s tales of a gold-rich kingdom to the south galvanized Francisco Pizarro, another early inhabitant of Santa María la Antigua, to set off on his bloody and treacherous conquest of the Inca. (Meanwhile, the Cueva were driven to extinction by violent Spanish conquest, European diseases and conflict with the Kuna people migrating north from Colombia.)

But the prominence of Santa María la Antigua was short-lived. Five years after Balboa’s voyage, the discovery of a flatter, quicker route allowed the Spanish to lay the foundations for Panama City. Santa María la Antigua was abandoned, then sacked by Indigenous groups—and the Darién fell quickly into an obscurity that made it a natural habitat for outlaws, including British pirates who used it to harass their Spanish rivals.

The Darién, graveyard of empires

In 1698, Scottish banker William Paterson hatched a scheme to colonize the Darién in the name of the Scottish empire. The former Bank of England governor had never set foot in Panama; his bold plan to create a “Scottish Amsterdam of the Indies” had been met with ridicule. Hindered by poor preparation, cut off by an English trade ban and besieged by the Spanish, only a few hundred of the 2,500 Scottish settlers who set foot in the Darién made it out alive.

Paterson’s failure bankrupted the Scottish economy, helping force Scotland into unification with England in 1707. But his idea of using the Darién to control “these doors of the seas … to give laws to both oceans, and to become the arbitrators of the commercial world” would inspire future daredevils and utopian thinkers. After the discovery of Californian gold in 1848, the race to find a sea route to the Pacific focused on the Darién, where the distance between the oceans was shortest.

In 1854 a U.S. expedition disappeared for 49 days in the jungle, battling starvation and insanity. Its leader, naval officer Isaac Strain, concluded the mountains made Darién “utterly impractical” for a canal. In 1870 the U.S. tried again, with an expedition team of over 100 men, an arsenal of the era’s most modern surveying equipment and a telegraph cable rolled out all the way to New York. But “in spite of the most careful preparations,” wrote captain Thomas Selfridge, “the expedition also depended upon extraordinary persistence and willingness to endure hardships.”

Promises of an easy Darién route had turned out to be a fabrication, but the idea of a sea-level canal in the Darién refused to die. In 1964, 50 years after the opening of the Panama Canal, the U.S. and Panama agreed to investigate the option of using 325 nuclear explosions to blast a 60-mile trench through the territory. A New York Times article suggested that the nuclear fallout would be safe given the deep jungle was only “sparsely populated.”

Connecting the Americas?

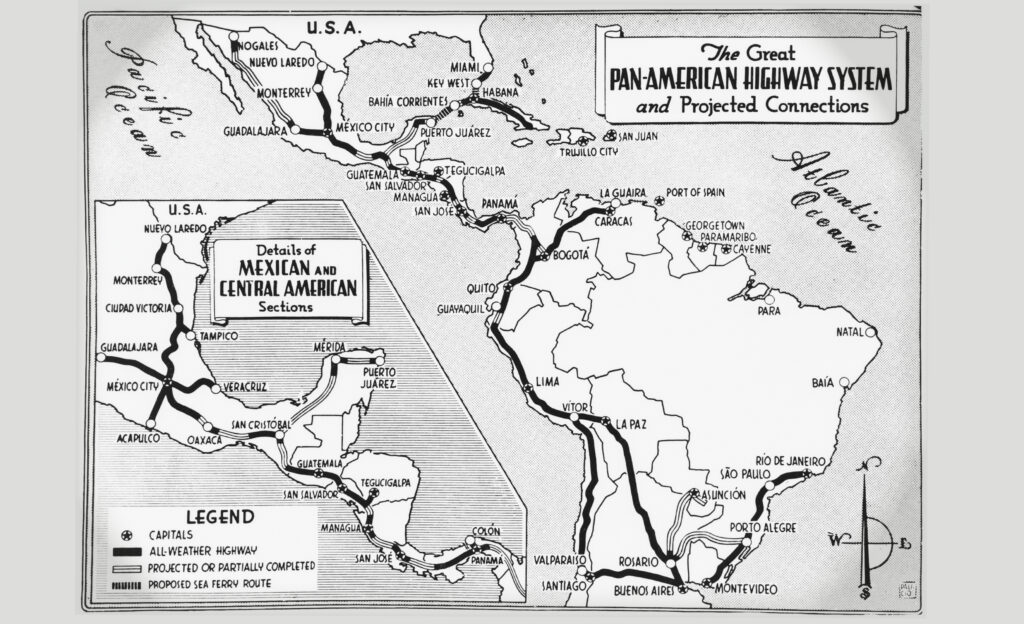

If the goal of connecting the oceans was a military and trade imperative for the U.S., the idea of connecting North and South America through the Darién was founded on Pan-Americanism, the ideal of greater commercial and cultural cooperation throughout the Western Hemisphere. At the Fifth International Conference of American States, held in Santiago in 1923, the idea of linking the Americas by road was first proposed, and in 1937 Canada, the U.S. and 12 Latin American states signed the Convention on the Pan-American Highway, each committing to build their sections of a road stretching from Alaska to Patagonia. In 1960 a crew from the National Geographic Society, including Araúz’s parents, crossed the Gap in jeeps. It took 101 days, averaging three miles a day, and required the construction of 125 makeshift bridges. The next year National Geographic magazine hailed the possibility of a road through the area.

“By the 1970s everything was ready,” said Omar Jaén, a Panamanian historian. “The U.S. had agreed to pay two-thirds of the construction costs for the Pan-American Highway, with Latin American countries paying one-third.” U.S. President Richard wanted to drive through the Gap in time for the 1976 bicentennial and hoped the Darién section might be named after him. The project became seen as “the material embodiment of Pan-Americanism.”

But the moment passed. In Panama, the arrival of the nationalist military government of Omar Torrijos shifted the focus of U.S.-Panamanian relations to negotiations over the future of the Canal and the surrounding U.S.-controlled zone. In South America, particularly Argentina, the highway came to be seen as a tool of U.S. imperialism and, following the election of Ronald Reagan, the U.S.’s principal goal in Central America became aiding the fight against left- wing guerrilla groups.

In an atmosphere of growing environmentalism, in 1977 the Sierra Club sued the U.S. Department of Transportation, claiming a Darién road would be a disaster for the environment and Indigenous people. The argument that the Gap provided a natural barrier against foot-and-mouth disease swayed the decision in their favor.

That disease has since been controlled in South America, but opposition to the road on environmental and cultural grounds has remained strong. Thanks to its role as a land bridge between the Americas and a facilitator of biotic exchange between continents, the Darién is one of the most biodiverse spots on the planet, with one in five species being endemic to the region. The local Kuna people have also consistently opposed the road. “A road would brutally damage the ecology in the region,” said Araúz.

The Darién in crisis

Others believe that the current status quo is not sustainable. Over the last three decades, 40% of the region’s rainforest has been cut down for cattle grazing and mainly illegal harvests of precious woods, such as the rare cocobolo tree. The Clan del Golfo, Colombia’s largest criminal syndicate, has thrived by taxing the guides who charge migrants $70 to $150 to cross the Gap. The Darién province makes up a quarter of Panama’s territory but remains one of its poorest areas.

Many locals say a link to Colombia would benefit the economy through ecotourism and agriculture. In recent years, the idea of a rail link between the two countries has reemerged, with the argument that it would be kinder to the environment, boosting Panamanian GDP by up to 8% a year, with funds ear-marked for conservation and policing operations in the Darién. However, the project has yet to gain political traction and has little support from Panamanians overall.

For Jaén, popular rejection of a land link is a result of years of fear-mongering from the political elite, who use the “primordial fear” of the Darién as a cover for a deeper anti-Colombian sentiment.

“The Darién has been de-gapped in the most disorganized manner imaginable,” said Jaén. “There are no lines of communication, no authority and criminal gangs run the region. We have to de-dramatize the Darién Gap, remove the taboo. The Darién myth benefits no one.”

—

Youkee is a freelance journalist and researcher based in Panama City.