BUENOS AIRES — It seems the grass really is greener on the other side of the Andes.

Indeed, Chile continues to be seen as a role model in Argentina, invoked as a success story by politicians across the ideological spectrum. This may sound unlikely, considering the instability that has unfolded in Chile since 2019, but its image as the macroeconomic and social oasis of Latin America remains alive and well in Argentina. In the middle of Argentina’s deep crisis, and as presidential elections in October draw closer, Chile is treated as something of a political toolbox where it is possible to find examples of how Argentine politics could solve Argentine problems.

Perhaps most surprising of all: Chile’s popularity is a crossover issue in Argentina’s famously polarized politics. It is seen as a pool of public policies not only by the far-right and center-right end of the ideological spectrum, which seems natural given the historical hegemony of so-called “Chilean neoliberalism,” but for the leftist kirchnerista end also.

From Milei to Macri: Chile, as a mirror

Libertarian Javier Milei, who is gaining momentum in Argentina’s presidential race, is perhaps the most obvious fan of Chile’s example. Inspired by the Chilean system of school vouchers, Milei promises to bring a voucher system to Argentina, hoping that private money could lead to a reduction of state influence and greater competition among schools—and thus better choices for families. Argentina’s education system used to be Latin America’s finest by many measures but has now fallen well below the regional average.

Milei also points toward Chile as a model for the infrastructure sector, calling for eliminating state funding and embracing a private sector-led model “a la chilena.” He has in mind the Chilean Law of Concessions, in which private companies develop infrastructure plans in exchange for concessions to run these public services. This fits in with Milei’s overall initiative to reduce state spending and improve transparency, which he has named the “Chainsaw Plan.”

Chile has also helped provide intellectual ballast for Milei. Axel Kaiser, a Chilean libertarian best-selling author, has helped connect Milei to a more extensive libertarian network in Chile and beyond. Last year, Milei hosted the presentation of El economista callejero: 15 lecciones para sobrevivir a políticos y demagogos, Kaiser’s latest book, in Buenos Aires. The two share a concept of a political “caste” that is privileged, corrupt and deserves to be kicked out of office.

In the case of Juntos por el Cambio, the more moderate right-wing opposition bloc that includes former President Mauricio Macri (2015-19), Chile is synonymous with two structural conditions that Argentina lacks. The first is fiscal discipline, no matter who is in government. When Chile’s President Gabriel Boric visited Buenos Aires last year and declared that “we have to stop thinking that fiscal responsibility is a matter of rights,” the Juntos bloc applauded that comment. Boric’s decision to appoint Mario Marcel, former central bank president during the presidency of conservative Sebastián Piñera, as his finance minister was also seen as symbolic of a bipartisan consensus over fiscal stability that Chile values, and Argentina’s opposition is desperate to achieve.

The second structural condition present in Chile is the central bank’s independence. To the Argentine opposition, the heart of the country’s inflation problem is a political elite that is unable to curb spending and prints money to cover the gap. Martín Tetaz, a congressman and well-known economist from the Juntos coalition, is ready to present a bill proposal: “We need an independent Central Bank as soon as possible, like Chile,” he has said.

Finally, macrismo envies the Chilean faith in meritocracy, and praises the openness of its economy. An economist from the bloc, Martin Surt, has consistently invoked Chile’s relatively subdued inflation mainly in its clothing sector as proof that Argentina’s clothing price rises, now 14.5% higher than the already high general annual inflation, is not the product of global factors, as the government alleges, but of protectionism.

Cristina Kirchner also looks at Chile

Argentina’s left, led by the kirchneristas, has repeatedly praised the progressive transformation that seemed to be underway in Chile after 2019 protests–including the writing of a new Constitution and the 2021 election of Boric. Even though that process has lost momentum over the past 12 months, with the triumph of the Chilean right in the last election, Argentina’s left has still found much to like.

The porteña lawmaker Ofelia Fernández, one of the most hard-core kirchneristas, often hails the example of Chao suegra, or “Goodbye, Mother-in-Law,” a program of subsidies to help young Chilean couples to rent their own housing (in many cases, allowing them to move out of their in-laws’ residence). The program was created in 2013 by the then President, the conservative Piñera.

In a public speech in April, Cristina Kirchner, the current vice president and longtime leader of the Argentine left, congratulated Chile for its recent decision to nationalize lithium production. In March, she also referred to Chile twice in her so-called “master class” at the Universidad de Río Negro. She noted that Chile was one of just a few countries that have run a budget surplus in recent years, which she said was proof that running deficits–as Argentina repeatedly has–does not automatically condemn a country to a crisis. She also highlighted that even with Chile’s relatively small size, it managed to export some $40 billion in minerals a year, suggesting that Argentina’s potential could be even higher if properly managed.

“Chile is very narrow … with all respect, but it is narrow,” she said.

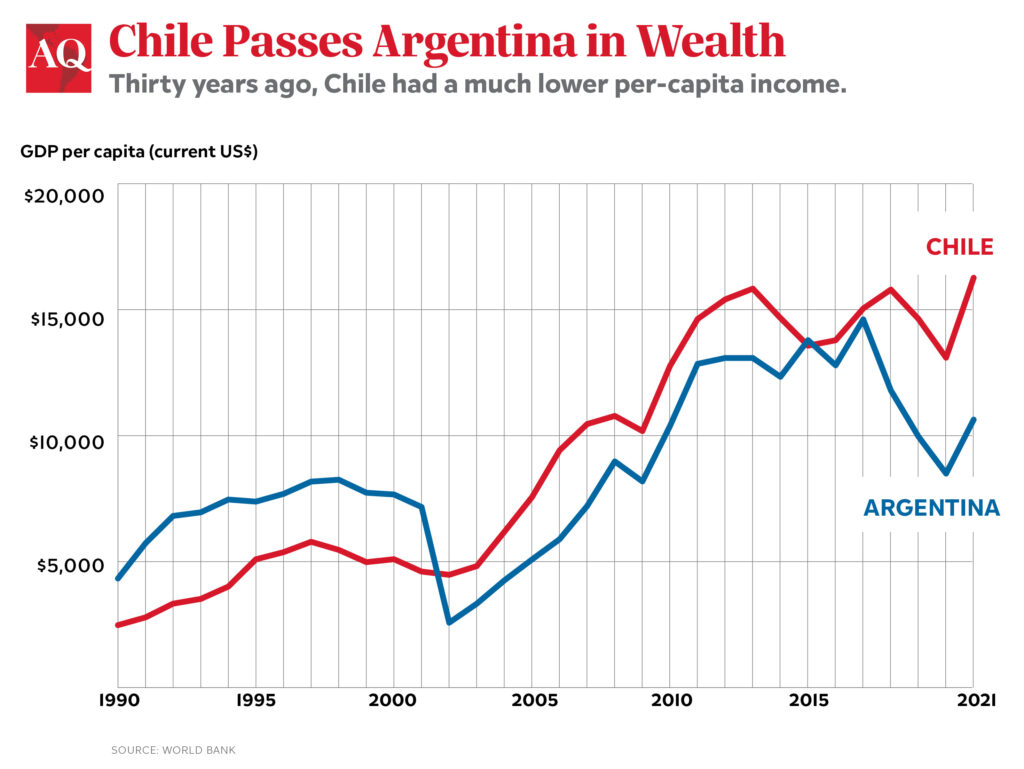

Behind Argentine politicians’ repeated praise of Chile hides a less convenient truth: Despite the mixed results of Chile’s recent political process, Chile remains in better shape than Argentina after decades of progressive public policies. In 2018, Argentina had the second-highest relative level of social spending in Latin America, at about 11% of GDP. Chile, with a much less generous welfare system, has reduced poverty to just one-third the level of Argentina according to international comparisons of poverty measured by the percentage of the population that lives with less than $5.50 per day. Whether Chile retains a grip on the Argentine imagination in coming years remains to be seen. It may depend more on the Argentine side and the capacity to overcome the continuous cycles of crisis that held Argentina back.

—

Vázquez is a journalist and political analyst based in Argentina. Her political columns appear weekly in La Nación, Buenos Aires, where she hosts “La Repregunta,” a web-TV show on politics and economics in the Southern Cone.