BUENOS AIRES AND SANTIAGO—Violence against women should be a thing of the past in Latin America and the Caribbean. Eighteen countries have special laws to deal with femicides, and yet, as homicide rates are falling, femicide rates are not.

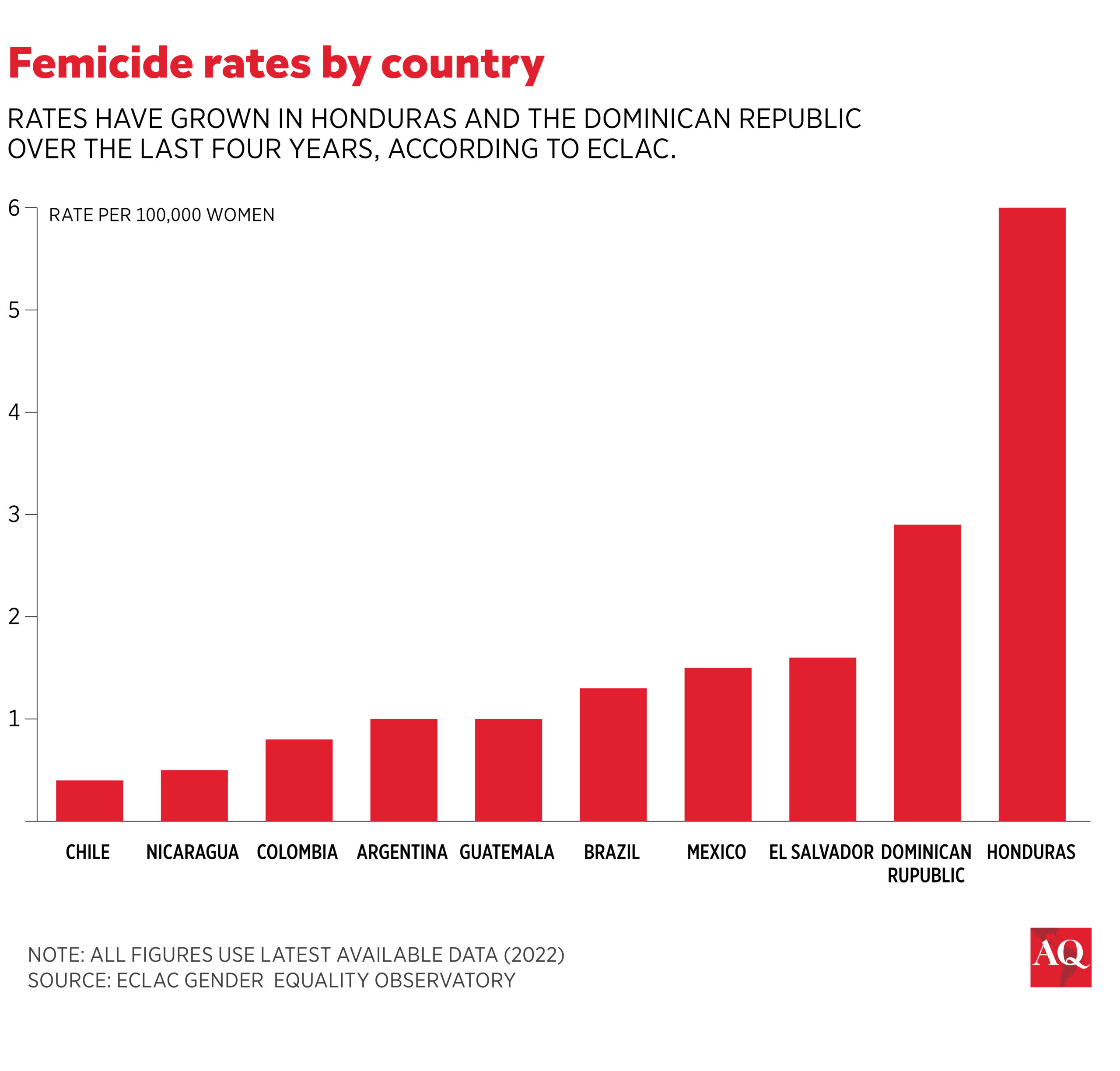

Instead, they are stuck at a stubbornly high plateau in most of the region. In 2022, the rate of femicide victims per 100,000 women ranged from 0.4 to 6.0 in Latin America and the Caribbean. Compared to the rest of the world, the Americas (including the U.S. and Canada) rank better than Africa and Asia but worse than Oceania and Europe, according to a UNODC study. However, it is problematic to compare figures among countries because they are based on different concepts and, above all, on different ways of measuring femicides. Furthermore, numbers across the region may be undercounted and comparisons made must be taken with caution. In some countries, only femicides committed by partners or ex-partners are included. Disappeared victims are not counted in eight Latin American countries, and the same happens in six countries when the aggressor commits suicide after killing the victim.

Nevertheless, figures remain high in every country. All this shows that having decent laws on the books isn’t enough. Once the right laws are in place, judicial and police systems must also make specific adjustments to address this particular kind of crime. A country’s legal system needs to be accessible to women and ensure they feel comfortable reporting crimes and participating in judicial proceedings.

In other words, legal systems must prove that they can avoid the re-victimization of complainants and can hold perpetrators accountable by securing convictions, meting out meaningful sentences, and working to both rehabilitate offenders and adopt preventive measures. International and regional regulations show how crimes against women can be investigated effectively through special due diligence—and how special precautions can be taken to prevent gender stereotypes from distorting the legal process.

The facts are clear, in the Western Hemisphere women are dying just because they’re women. Some are more likely to be victimized if they are members of marginalized groups, with race, ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status playing significant roles. These conditions of intersectionality lead some women to count on fewer supporting social networks, less access to justice, and greater economic dependence on their aggressors.

The faces of femicide in the Western Hemisphere

While it can be difficult to compare rates across borders because they lack common legal frameworks and measurements, it is clear that Honduras and the Dominican Republic have femicide rates well above the regional norm. Meanwhile, Mexico and Brazil rank highest in absolute numbers, with at least 976 and 1,437 women, respectively, murdered in 2022, the most recent year with data compiled by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

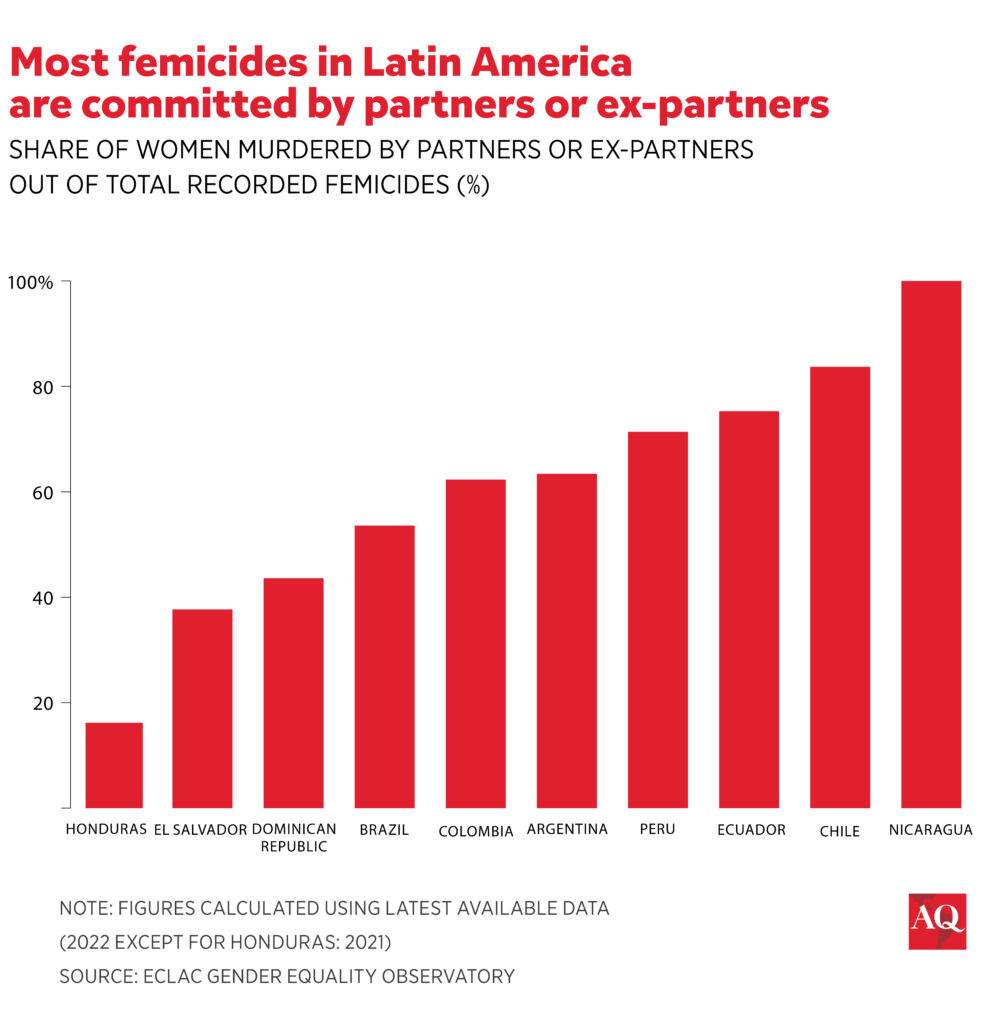

It is also clear that women are highly vulnerable in their homes. The vast majority of femicides in the region are committed by partners or ex-partners, according to a UNDP report. Their involvement reaches 100% of cases in Nicaragua and over 80% in jurisdictions from Chile (83.7%) to Puerto Rico (81.3%), although in some countries only this type of cases is considered femicide.

Still, even though the majority of femicides occur in the domestic sphere in most of the region, the opposite is true in countries with the highest rates of this crime: Honduras, El Salvador and the Dominican Republic. This indicates the involvement of organized crime, especially gangs, who use women as commodities, then kill them to keep them quiet or exact revenge on rivals. It also indicates that specific measures need to be taken to reduce the toll inflicted by these gangs.

Beyond legislation

It is essential to recognize the progress of the last four decades, through which violence against women became more visible. The sustained advances in gender equality are mainly due to the work of social organizations and feminist movements that have fought and won political battles.

The Belém do Pará Convention, sponsored by the Organization of American States (OAS) and ratified in 1994, was a milestone in this fight. It requires states to make extensive commitments to combat violence against women, including passing legislation, adopting preventive measures, ensuring fair and effective legal procedures, and guaranteeing compensation. This kind of wide-ranging policy mix should be maintained. Violence against women takes many different forms: physical, psychological, symbolic, economic, sexual, and others. This is why ambitious laws are required that consider women in all their diversity and violence in all its forms, and that address the historical roots of femicide and its material and symbolic dimensions.

Argentina, for example, has laudable legislation on gender violence, which mandates data collection to understand the issue and make it visible. A 2009 law requires authorities to keep detailed information on victims, alleged aggressors, the relevant events, and the responses from the justice system. Since 2015, Argentina’s Supreme Court has periodically prepared a national registry of femicides that includes this data.

The most recent edition, published on June 1, shows that there were 250 direct victims of femicide in 2023, 10.6% more than in 2022, when 226 cases were registered. Both years were below the pre-pandemic level that peaked in 2019 at 260 victims. Argentina’s last year figures show that even though the numbers are not at record highs, the problem is still stubborn, and quantifying it is insufficient.

Challenges ahead

Governments and international and local organizations have made substantial progress in recent decades, but the region still has a long way to go. The figures make it clear that, despite their efforts, decision-makers and society as a whole need to be more proactive to tackle this pressing problem.

This requires clear coordination between various branches of government, from the local level to the national level. It also means maintaining a constant dialogue with civil society, in its different layers and capacities. It is not an easy task, but it has never been easy. It is our challenge to do better as a region.