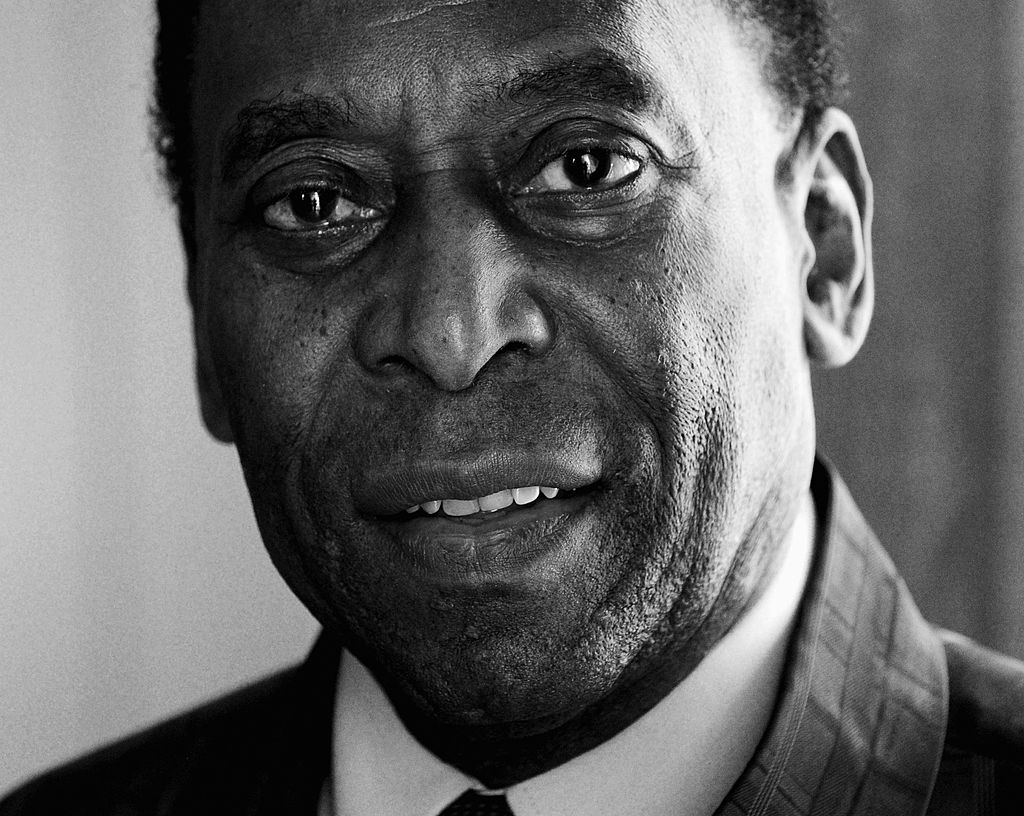

The first time I met Pelé, I, like most mortals, had no real idea what to say. An American publisher had hired me to help him write a book for the 2014 World Cup, which Brazil was hosting, but they didn’t want just another traditional soccer memoir recounting long-ago goals and other glories. (Pelé had already published two such books in English–the first in 1977, the year he retired from the New York Cosmos and also, coincidentally, the year I was born.) So when we sat down at his office in Santos, surrounded by aging photos and trophies, I decided to try a different, more personal approach:

“Pelé, I saw a photo from the 1970s of you sharing a table at Studio 54 with Rod Stewart, Mick Jagger, Liza Minelli and Andy Warhol. What was that like? What do you remember?”

Pelé smiled–that big, iconic smile. “Rod Stewart! A great guy! He loved soccer, loved Brazil. Always quick with a joke. So funny. Great guy.”

I waited a moment. Was that all?

Yep, that was all.

OK, I thought, maybe things got a little wild back in the seventies. What happens at Studio 54 stays at Studio 54? Fair enough. Let’s try another one:

“Pelé, you attended Michael Jackson’s 18th birthday party. What was that like? How did Michael change over the years? How did you feel when he died?”

That smile again. “Michael Jackson – great guy! Loved Brazil, loved the dance of our people. He always wanted to talk about Brazil, about our traditions. Really a spectacular guy.”

This continued in more or less similar fashion for another hour, and I walked out of that first meeting feeling… utterly consumed by panic. Because of the agonizingly slow manner in which books are produced and printed, and an inexplicable bit of brinkmanship by our publisher, we only had nine weeks to do the interviews, write and edit this book. Where on earth would I get the material? I recounted our conversation to a few trusted friends, and they all had the same reaction: Was Pelé senile? Or just not very smart?

I soon discovered that, in fact, I was the one who was not very smart. Pelé had been one of the world’s most famous people since leading Brazil to its first World Cup championship at the age of just 17, in 1958. In ensuing decades, Pele crossed paths with Queen Elizabeth, Muhammad Ali, and the Beatles. He met numerous popes, and every U.S. president since Lyndon Johnson. He starred in a Hollywood movie alongside Sylvester Stallone and Michael Caine. Which is all to say: Of course Pelé didn’t remember much about that night at Studio 54, because it probably didn’t make much of an impression. He had met every celebrity from the second half of the 20th century onward, and none were more famous than him.

So the next time we sat down, I skipped the celebrity gossip, and tried to get to know the man on his own terms. I would only partly succeed: Pelé had been burned by countless people over the years, losing his entire fortune not once but twice to bad investments and outright fraud. He learned the hard way not to trust agents, accountants, ghostwriters and others who were supposedly there to help him. From what I could discern, it wasn’t extreme fame that posed the biggest challenges for Pelé–in fact, he had been so famous for so long that it was all he could remember, and he told me he had nightmares about no one remembering who he was. No, what brought Pelé the most trouble was the friends and others who constantly sought money, favors, tickets, an angle. He treated me politely, but warily, as if I was another person who was inevitably going to let him down.

Despite these barriers, I learned there were two things that Pelé seemed to genuinely care about.

The first thing, of course, was soccer. Nothing animated Pelé quite like stories of his time on and around the field–his unmatched three World Cup titles, the go-go Santos era, the twilight years of his career when he was the unquestioned king of 1970s New York City, and he introduced soccer to many Americans for the first time, playing for the Cosmos. Pelé had clearly told some of these stories thousands of times, and frankly a few of them might not have withstood the rigors of modern-day fact-checking. But he seemed to most enjoy the tales from his earliest days, from a world before the advent of mass communications or pop culture, a world that no longer existed for him–or anyone else.

He told me about walking through the streets of Sweden, the host nation of that first 1958 Cup, alongside his Brazil teammates, among them the beloved Mané Garrincha who, like Pelé, was something of a country bumpkin in those early years. They spotted a new invention not yet available in Brazil, battery-powered radios, and began testing the speakers. Garrincha turned up his nose and declared he would never buy such a thing. One of the older players, surprised, asked why. “I don’t understand a damn thing it says!” Garrincha replied. The voice coming through on the radio was, of course, in Swedish. The other players tried to explain that the radio would “speak” Brazilian Portuguese back home, but Garrincha didn’t believe them. “No way, no way.” Some 60 years later, tears of laughter still came to Pelé’s eyes—along with a certain nostalgia.

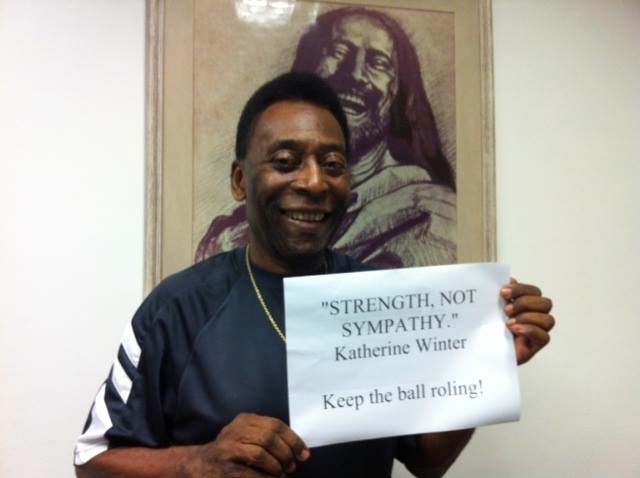

The second thing that Pelé cared about was perhaps more surprising. Despite all the exploitation over the years, despite countless encounters with breathless fans and heads of state and celebrities of a lesser vintage, Pelé still seemed to take an authentic joy in connecting with people. Not everybody, mind you–everyday adults, with their hidden agendas, didn’t interest him much. But with children, and especially with the ill and otherwise vulnerable, I saw this man repeatedly make the effort to understand what people wanted, and then be generous enough to give it to them. On visits to hospitals, and his charity projects, he would spend time, real time, talking to people. Many of them were, like me, too young to have ever seen him play futebol–but even small kids seemed to intuitively understand this was a person of special magic and charisma. I asked Pelé if he ever tired of autographs and small talk. “Sometimes,” he allowed. “But I think God put me here to try to make people happy.” If that sounds hokey or rehearsed to you, I understand. But I believe he meant it.

I believe this in part because, as fate would have it, my family would experience this side of Pelé firsthand. During the short time Pelé and I worked together, my younger sister was diagnosed with a highly aggressive cancer at the age of just 30. As we worked on the book, Pelé asked about her regularly. When things got really tough, he took a photo of himself—smiling, of course—holding a sign bearing her name and a message, complete with typo: “Keep the ball roling.” My sister simply couldn’t believe it. “Omg love it,” she replied. That was the last message I received from her. I know Pelé touched hundreds, and probably thousands, of people in the same way, far away from the spotlight and cameras.

None of this made Pelé a saint, of course. In Brazil, where I lived during those years, it was common to hear people say they loved Pelé, but they did not like Edson Arantes do Nascimento—drawing a distinction between the soccer icon and the real-life human being (Edson was his given name). His refusal for years to recognize a daughter born out of wedlock, even after DNA tests proved she was his, alienated a great many fans. Others complained about his crass commercialism, his constant need to cash in over the years with Pelé-brand coffee, candy bars, pharmacies and even cattle. To those close to him, he could be distant and aloof, showing little of the generosity he displayed toward total strangers.

I suppose Pelé, like all of us, had to live with the consequences of his failures and shortcomings. All I can say is this: I cannot personally imagine living the bizarre life trajectory of the superstar athlete, whose fame and earning power peaks sometime in their twenties, only to spend the next four, five, six decades being asked to relive crusty old stories that must, as the years pass, begin to seem like they happened to someone else. I have spent my career working with presidents and other famous figures; none of them generated anything remotely like the sheer hysteria that Pelé provoked in otherwise normal-seeming people. I saw grown men cry, and their hands tremble, in his presence as they recounted some goal he scored for Santos in 1960-something. In retrospect, it seems entirely plausible that even Rod Stewart and a young Michael Jackson may have, at the peak of Pelé’s celebrity, only managed to blurt out a few words about loving Brazil and the “dance of your people.” Maybe Pelé’s recall of those conversations at Studio 54 was actually perfect. It wouldn’t surprise me.

The book Pelé and I wrote together, Why Soccer Matters, was published–on time, miraculously–on the eve of the 2014 World Cup. It wasn’t the groundbreaking novelty the publisher hoped for; instead, it mostly retold the old stories, the ones Pele wanted to tell, and everybody wanted to hear. We lost touch soon afterward; I knew him only briefly. But the most honest sounding observation I ever heard came from his closest aide, José Fornos Rodrigues, known as “Pepito,” a true gentleman whom he did, by all accounts trust and confide in. “At this stage in his life,” Pepito told me, “Edson is an actor who plays the role of Pelé.” Yes, it was a performance, but it was a genius performance, one in which he gave more of himself than he had to, even when hardly anyone was watching. He made a great many people happy. May he rest In peace.