In December of 2008, in the wake of Nicaragua’s fraud-ridden local elections, I wrote a piece calling for the international community to prevent the country from morphing into the Western Hemisphere’s Zimbabwe, and Daniel Ortega from becoming Robert Mugabe. The election, held without reputable international observers and under the complacent gaze of a government-controlled electoral authority, was the first tangible sign that the end of the country’s brief democratic interlude was no longer a risk – it was a reality.

Nothing much happened. A few European developing agencies discreetly left the country, while the U.S. government added a bit of huffing and puffing, eager to keep Ortega on the right side of counter-narcotics efforts. Most of all, in a pattern that would repeat itself incessantly until this day, there was silence coming from Nicaragua’s Central American neighbors, with the intermittent exception of Costa Rica.

What followed was an ineluctable descent into authoritarian rule defined by the government’s co-optation of all institutions, the shrinking ability of opposition parties and civil society to operate, the constant harassment of independent media, and the complicit silence of powerful actors in society, notably the business elite. All this happened in broad daylight, and yet was strangely unseen. Occupied with Venezuela’s never-ending calamity, no one in Latin America and beyond seemed to have the bandwidth to pay attention to another democratic breakdown in the region.

Not even Ortega’s violent crackdown of anti-government protests in 2018, which led to hundreds of deaths, was enough to shake the region and the world into action. Confronted with evidence of egregious human rights abuses, which made a mockery of the lofty principles proclaimed by the Inter-American Democratic Charter (IADC), the Organization of American States’ (OAS) Permanent Council adopted a resolution condemning the violence in Nicaragua and calling for elections. Ortega provided vague assurances of future electoral reforms, and the matter was left at that.

It is through this combination of empty rhetoric, short attention spans, and expedient silence that Nicaragua’s political degradation was allowed to fester and get here. And the here is worse than anybody imagined. In the run up to next November’s presidential election, in which he will try to win a fourth consecutive term, Ortega has embarked on a repressive onslaught unlike any other seen in Latin America since the region’s democratic transition. Not even Venezuela has experienced the jailing of five opposition presidential candidates and a long list of activists, independent journalists, and business leaders, in a matter of few days. Amidst the kidnapping and ransacking of homes of opposition figures by security forces, we are witnessing the shedding of any trapping of democracy and the rule of law left in Nicaragua. According to data from International IDEA, the country looks poised to join Venezuela as the only two countries in the world that in a span of two decades have moved from being functional representative democracies to full-fledged dictatorships through all the stages of backsliding and hybridity. Ortega has become the late Robert Mugabe. Worse still, he has become Tachito Somoza, the reviled tyrant he once deposed.

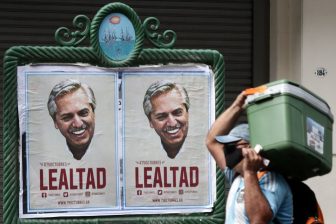

Yet, the symphony of impotency continues. True, the OAS managed to vote on yet another resolution rebuking Ortega’s regime, albeit weakened by the abstentions of Mexico and Argentina. While at a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, 59 countries signed a declaration condemning repression in Nicaragua and demanding the release of detained opponents. But Nicaragua continues to sit unperturbed at the OAS Permanent Council, where there is no appetite to apply articles 20 and 21 of the IADC, which allow for the suspension of a Member State where an unconstitutional alteration of the democratic order has taken place. The hapless Central American Integration System has not managed to utter a word, despite the fact that its foundational treaty commits its Member States to defending democracy and human rights.

Many lessons stem from Nicaragua’s tragedy. The first one is that, as with common criminals, impunity has signaling effects for autocrats. Why would Ortega refrain from doing what he’s doing, if all the messages he’s received from the region and the world over the past 15 years suggest that he will get away with it? This is why it is so important to, at least, invoke and apply the IADC in this case. The Charter is a landmark document in the political transformation of Latin America. Unlike Venezuela, Nicaragua is a very small country, devoid of strategic significance. If its government is allowed to trample with total impunity on basic principles of democracy and human rights, the IADC will become worthless. Would-be autocrats will take note. Remarkably, other regions with less democratic pedigrees seem to take their obligation to defend democracy more seriously. In late May, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) suspended Mali’s participation in the sub-regional bloc following a military coup. If West Africa can do that, the Western Hemisphere surely can too.

The second lesson is that when it comes to threats to democracy, we are yet to adjust our mental maps. Our instruments to defend democracy continue to be conceived and deployed in terms of threats that are far less important now than they were in the past, such as military coups or blatant electoral fraud. Crucially, they are conceived in terms of attacks to democratically elected governments, not in terms of assaults on democracy perpetrated by them. A democratic breakdown used to be simple to spot. Now the erosion of democracy comes in all sorts of shades of gray that render the threat more difficult to identify and counter. One of the remarkable things about the current repressive wave in Nicaragua is that the actions taken by the regime are neatly codified in laws and sanctioned by institutions co-opted over a long time.

Murky as it is, we know the playbook by now. We’ve seen it all over the world, from Nicaragua to Hungary to Turkey to Sri Lanka. And we all know that it invariably starts by compromising judicial independence, harassing critical media outlets, and controlling electoral authorities. Attempts by incumbents to do any of those things should trigger alarm bells and spring mechanisms to protect democracy into action. This is particularly true about attacks against electoral authorities, a point that is borne by the Nicaraguan experience. Free and fair elections continue to be the single most important check on power, as recently shown by the mid-terms in Mexico. As political scientist Adam Przeworski has put it, democracy is, at its core, a system where parties lose elections and are willing to accept it. We need early warning systems against backsliding and democratic clauses—including those in the IADC—reinterpreted for the current world.

Passivity in the face of the symptoms of democratic decay that we all have learned to recognize breeds monsters down the road. What is urgent now is that the impunity that has sheltered and emboldened Daniel Ortega comes to an end. That starts with suspending Nicaragua’s participation in the OAS as soon as possible, if only to show that the IADC still has a pulse. Otherwise, the long-term consequences for Latin America’s fragile democratic experiment will be dire.

—

Casas-Zamora is the secretary-general of International IDEA and a former vice president of Costa Rica