This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America

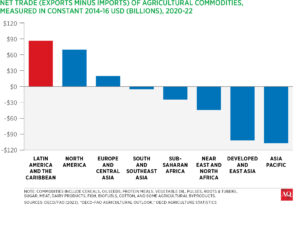

A year ago AQ published a special report exploring a paradox in Latin America: Although the region produces and exports more agricultural products than ever before, it struggles to feed its own people.

A year later, the news remains worrisome, tied as it is to structural, long-term causes. The food paradox persists, with food insecurity currently affecting 25.2% of the population, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). That is higher than a decade ago (in 2015 it was 23.7%), part of a global rise.

However, the situation is getting a little bit better. Food insecurity levels have been declining gradually since hitting a peak during the pandemic, and they maintained that downward trend in 2024 (25.2%) compared to 2023 (26.7%).

Experts say the recent drop is thanks to the economic recovery in several South American countries, fueled by social safety nets, post-pandemic recovery moves, and policies aimed at improving access to food. Brazil is a good example. Since 2023, Brazil has reactivated its food security policies, expanding school meals and a food acquisition program, and strengthening family farming. Cash transfers still matter, but the poorest also saw their earnings increase in 2024. And after finding itself on the UN’s world hunger map in 2021, following shifts in public policy priorities and the impacts of the pandemic, Brazil is now off that map again.

Business as usual

Overall, experts say, the reduction is not that impressive. “It’s very strongly linked to challenges that got resolved after the pandemic was over. So, I think it’s almost like going back to business as usual,” said Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, a professor of public health at Yale.

“Hunger and lack of food are not the same thing. The problem lies in access, distribution, and the resources needed to produce or buy food, as well as the distribution of the food itself,” said José Graziano, a former director general of the FAO who helped design Brazil’s “Zero Hunger” program in the early 2000s. The “food paradox” can also be understood as a logical outcome of the system itself. Global commodity markets and export-oriented agriculture affect local food availability and affordability, as the push to export can drive up prices for those same staples at home. In the meantime, difficulties in accessing food, especially healthy food, remain—and people and organizations across the region are seeking to address them. In last year’s special report AQ profiled some of these groups.

In Argentina, where the prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity went from 19.2% in 2014 to 33.8% in 2024, Banco de Alimentos de Argentina continues to deliver on its target. In 2024 they delivered 21,000 kilos of food to 4,000 organizations that reached 882,000 people.

In Mexico, The Hunger Project’s program led by Indigenous and rural women has grown in Chiapas and Oaxaca, now reaching 469 participants who are strengthening family gardens, forming savings groups, and launching small businesses. Women have begun earning modest but rising incomes while gaining more control over household spending and savings. Challenges remain, from climate change to reliance on cash transfers, but leadership and autonomy are clearly emerging, exemplified by 19-year-old Luisa Fernanda Ruiz Pérez, who has turned her textile business into a training platform for others and was recently invited to showcase her work at a national crafts fair.

In Oaxaca, local NGO Mbis Bin, which means “seeds for sowing” in Zapotec, continues to provide training to promote sustainable agriculture in a state where one in four are affected by food insecurity. They’ve organized training on chick incubation; vanilla cultivation; bio-inputs; and planting organic vegetable gardens following the milpa method, a Mesoamerican planting technique in which a variety of fruits and vegetables are interspersed in the same plot. All of this can provide both nutrition and income to rural households.

“I think of the matter of dealing with hunger as a film: You have the main characters, which are jobs and income, and the supporting characters, which are these smaller programs. You can’t make the film without the first, but all are important to the script,” Graziano told AQ.

As the region slowly makes its way out of the depth of food insecurity, another concern has arisen: obesity rates. The prevalence of adult obesity increased from 12.1% in 2012 to 15.8% in 2022. “We have learned a lot about how to address hunger, but we still don’t know how to fix the problem of obesity,” Graziano said.