This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on the politics of water in Latin America | Leer en español

LIMA — When the conquering Spaniards founded the City of Kings, today known as Lima, in 1532, they evidently had no idea how problematic the location would turn out to be.

The Peruvian capital is now famously the world’s second largest desert city, after Cairo. Yet while the Egyptian capital has the mighty Nile, Lima’s three highly seasonal — and often polluted — rivers flow at an average of less than 2% of their African counterpart.

Today, the Peruvian capital faces a looming water crisis compounded by climate change and chaotic, unregulated urban growth. An estimated 1 million of Lima’s 10 million residents lack access to potable water, and although that number has been falling recently, SEDAPAL, the city’s water utility, urgently needs to increase the supply to maintain the trend.

But if Lima’s water problems are as old as the city itself, the solutions may be even older. Policymakers here are now turning to pre-Columbian technology to help prevent taps from running dry. The approach promises to complement Lima’s existing efforts and serve as a model for how other Latin American cities can tackle similar water crises using innovative approaches.

After investing billions over the years in a series of high-altitude lagoons and other “gray” infrastructure, SEDAPAL is adding to its supply portfolio a potentially much cheaper solution to meet growing demand: restoring ancient stone channels, known as amunas, in the remote, mountainous watersheds above the city.

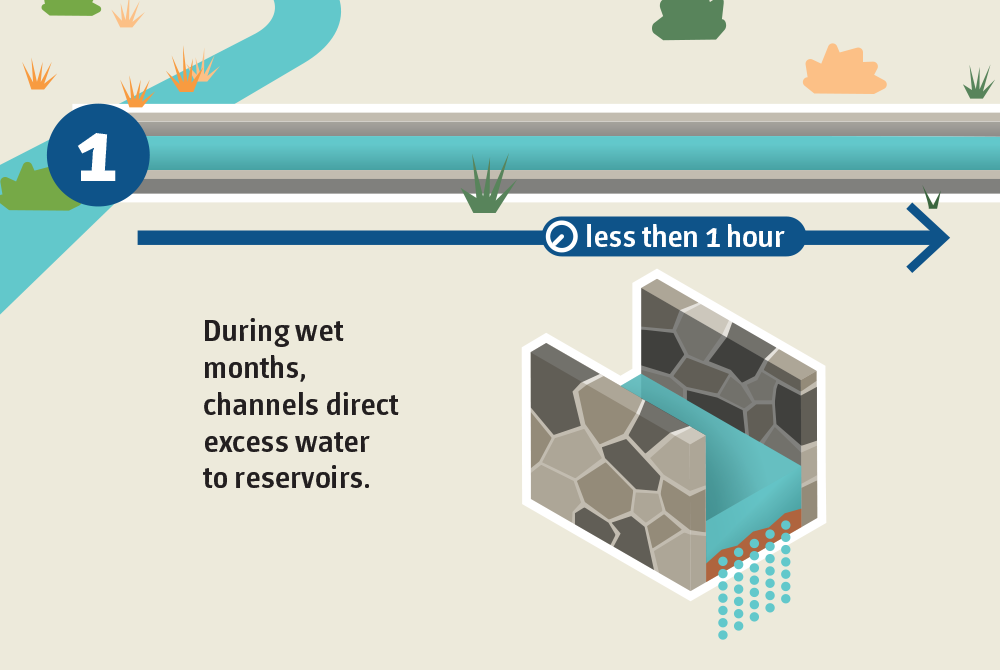

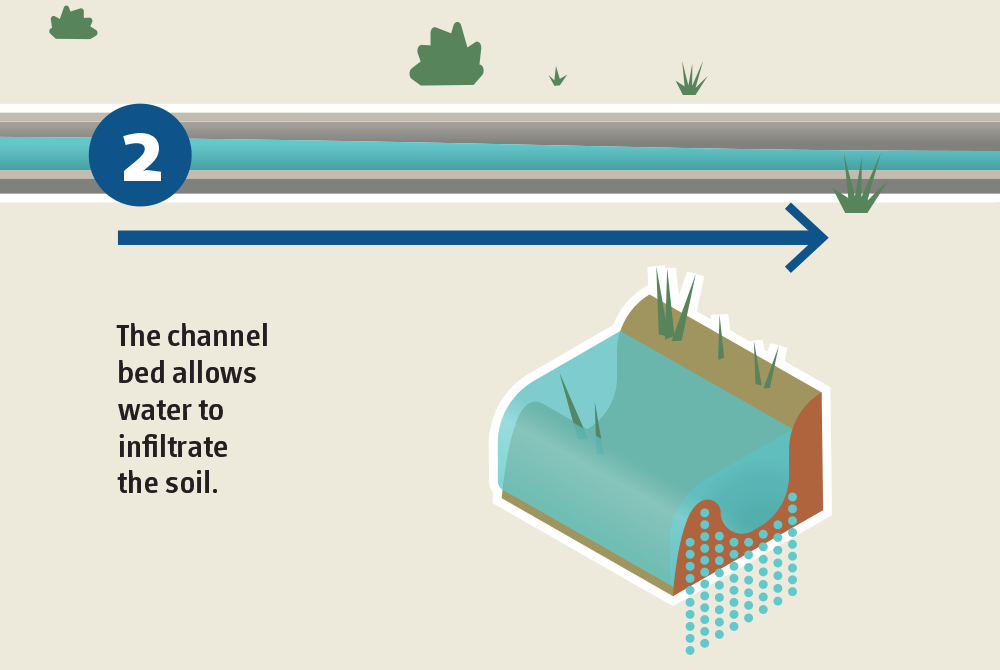

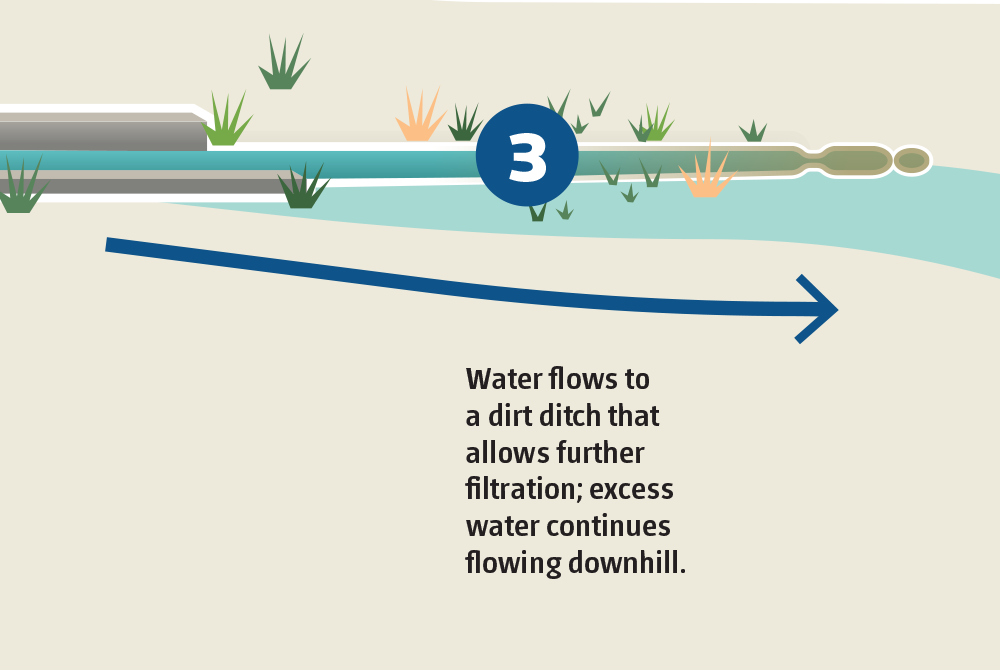

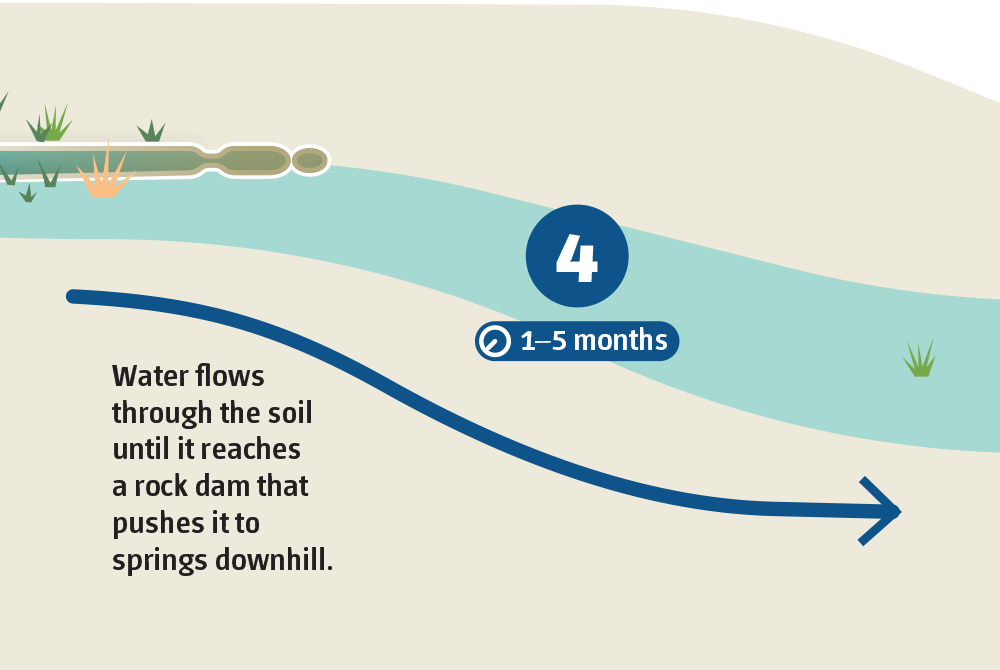

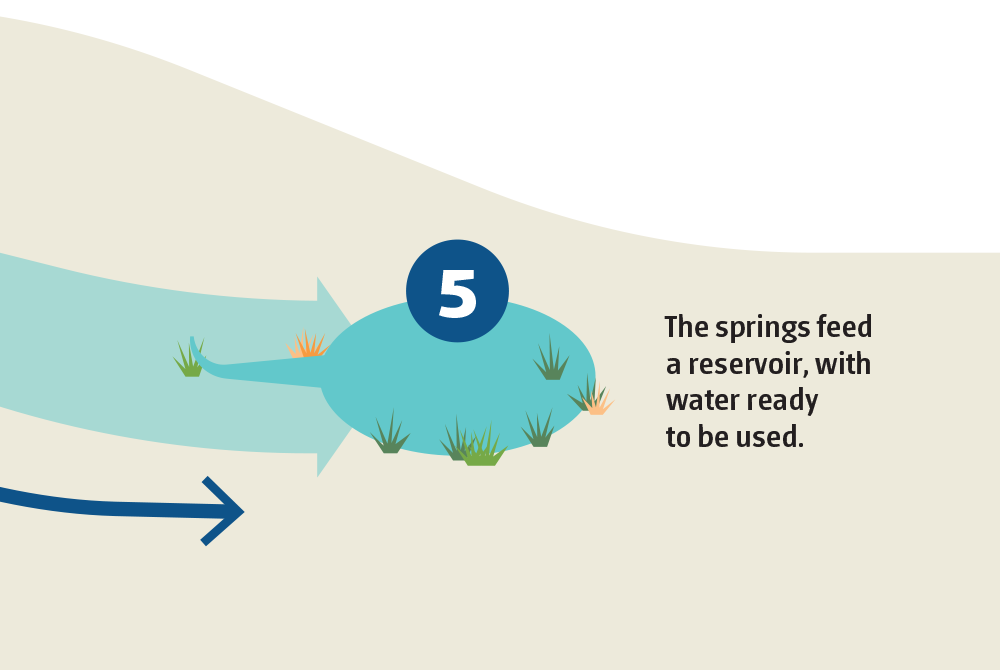

During the wet season, the amunas divert surface water to infiltration ditches, where it is absorbed into the soil, replenishing the water table. It then emerges weeks and even months later in natural springs and human-built stone pools. By helping to modulate the drastic changes in seasonal flows, the pre-Incan system, known as mamanteo, will allow SEDAPAL to use the water more efficiently, in particular during the rainy season when the company is unable to capture the excess volume in Lima’s two most important rivers, the Rímac and Chillón.

So far, a pilot project in the village of Huamantanga, 10,000 feet up in the Andes, has proved highly promising. One amuna roughly one mile in length has been restored, dramatically changing water yields, both for locals who rely on it for their subsistence agriculture and for the discharges farther downstream.

Source: Sam Granger/Imperial College London/Soapbox Communications/Condesan

The project is being complemented with measures to restore the puna, spongy Andean grasslands above the tree line, including replacing exotic cattle with native llamas and alpacas. The puna ecosystem is particularly slow to grow and regenerate but, when healthy, stores huge amounts of water, releasing it slowly during the dry season.

The Huamantanga pilot is part of a program called Natural Infrastructure for Water Security, being run along the Peruvian Andes by a consortium of environmental NGOs, including CONDESAN and the U.S. Forest Trends, along with Imperial College London.

The initiative has been funded with $27 million from USAID and the Canadian government. But its long-term success, to be financed by local water utilities, seems likely thanks to important regulatory reforms.

Peru’s Sanitation Services Modernization Law, passed in 2013, established a funding mechanism for watershed conservation. The Mechanisms for Ecosystem Services Compensation Law, passed the following year, established a legal framework for the public and private sectors to reward upstream communities like Huamantanga for protecting and restoring water sources.

The new legislation has allowed SEDAPAL to raise its rates in order to dedicate 1% of revenues to “natural infrastructure” and another 3.5% to climate change adaptation — an innovative model for the region, said Hugo Contreras, director of water security for Latin America at The Nature Conservancy.

“By making utilities share responsibility for water sources, not just distribution, there are now more resources for conservation,” Contreras told AQ.

So far, the utility has raised some 70 million soles ($20 million) for “natural infrastructure” purposes. That money has yet to be spent, but, assuming the amunas project continues to yield positive results, a chunk of it will be dedicated to restoring mamanteo systems in Lima’s watersheds.

The Atarjea water plant treats Lima’s precarious supply of drinking water. (Crédito: Fotoholica Press/Lightrocket via Getty)

The Atarjea water plant treats Lima’s precarious supply of drinking water. (Crédito: Fotoholica Press/Lightrocket via Getty)

According to SEDAPAL, Lima needs an additional 3.05 cubic meters of water per second just to meet existing demand. Researchers working on the Huamantanga pilot have calculated that together these measures could make up 2.74 cubic meters per second of that deficit.

Meanwhile, the amuna project has required extensive discussions with the community of Huamantanga, which has a population of 600. Incentives for the villagers have included technical advice that could significantly improve the productivity of crops and livestock. Yet even so, there has been resistance.

“The biggest challenge is changing the mindset, the way of thinking,” says Javier Antiporta, of CONDESAN, one of the NGOs executing the project. “People ask why should they change if they have always done things this way. You have to explain that they will be the first beneficiaries of this. That they will have more water for themselves and their agriculture.”

An amuna diverts surface water to infiltration ditches, where it is absorbed into the soil. (Credit: AquaFondo/Facebook)

An amuna diverts surface water to infiltration ditches, where it is absorbed into the soil. (Credit: AquaFondo/Facebook)

The potential is huge.

Huamantanga has 11 amunas totaling nearly nine miles. It’s not clear exactly how many other mountain communities in Lima’s watersheds, and across Peru, have existing amunas, but building new ones could also be an option.

As the source of the Amazon, Peru is actually hydrologically blessed. However, 98% of the country’s precipitation runs east, toward the Atlantic. But nearly 20 million of the country’s 31 million residents live on the arid Pacific coast. Half of them are in the capital, but there are many other cities on Peru’s narrow littoral that could also benefit from mamanteo systems.

These green techniques are also more cost-efficient, by orders of magnitude, than conventional, concrete-heavy technologies such as reservoirs and trans-Andean pipes. While using amunas costs $0.004 per additional cubic meter of water, according to researchers, building new reservoirs and associated infrastructure will cost between $0.10 and $0.25 per cubic meter. A new desalination plant being built just south of Lima will cost more than $0.73 per cubic meter of water.

For Francisco Dumler, head of SEDAPAL, reviving the amunas is a crucial component of the company’s strategy of diversifying water sources, which will also require more desalination plants on the coast, even though they are so much more expensive.

“It’s not just about the cost benefit,” said Dumler. “It’s about risk management. We are facing high levels of hydrological stress over the next four to six years. We need to be looking at innovative solutions.”

—

Tegel is a freelance journalist based in Lima