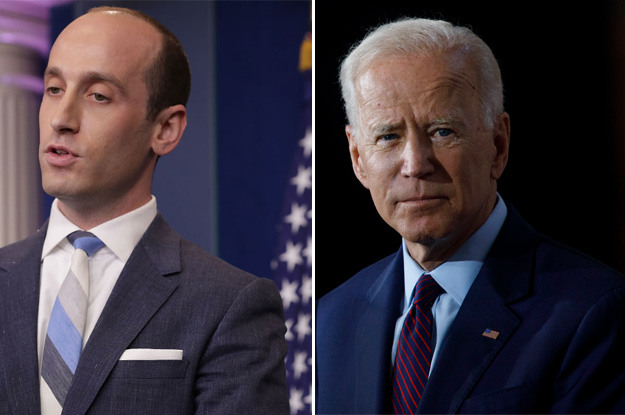

To the extent that the Trump administration has a policy toward Latin America, you could call it the Miller Doctrine – as formulated by White House adviser Stephen Miller, whose “zero tolerance” family separations have been a defining policy of Donald Trump’s time in office.

Of course, Miller isn’t only looking at Latin America; he’s an equal-opportunity restrictionist when it comes to keeping people out of the United States. But his agenda has nonetheless dominated the White House’s view of the region, and become even more pronounced amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, thousands of asylum seekers from Central America’s Northern Triangle are being returned to Mexico after an average of only 96 minutes of processing. Along with Venezuela and a sprinkling of Cuba policy, these deportations have accounted for the lion’s share of U.S. engagement with Latin America since 2017.

With November presidential elections on the horizon, it is time to think about U.S. policy toward the region not just for the next four years, but the next 20. Especially as Latin America is itself in flux, its people and economies pummeled by the pandemic and democratic institutions from El Salvador to Brazil under stress.

Democratic candidate Joe Biden has become more publicly critical of the past four years of U.S. engagement (or lack thereof) with the region. He has sought to put forward his own vision, with a more accommodating stance on immigration and greater U.S. involvement in hemispheric matters. But even if he is elected, a return to some kind of Obama-era status quo seems unlikely, for several reasons.

First, because Trump’s game of economic hardball with Beijing could have lasting ramifications for Latin America, given that China is the region’s number one trade partner. Trump’s mercurial behavior on tearing up NAFTA and “building the wall” have also made millions of Latin Americans shudder at what they see as a crude caricature of the already imperious Tío Sam. What’s more, the region has undergone considerable, in some instances permanent, change since Obama left office – not least with the ebb of the leftist Pink Tide and plunge in commodity prices from just a few years ago.

Indeed, a brief look at the history of U.S.-Latin America ties highlights how we are already in uncharted territory.

End of the Pan-American spirit?

U.S.–Latin American relations have seen their share of rocky moments, but Trump’s behavior toward the region is sui generis.

The conventional, generally critical, assessment of U.S. motivations and actions over the past 200 years fully merits the description of the United States as an imperial power or malign hegemon. Tío Sam’s historical legacy is one of Navy gunboats, plots to legalize slavery in Central America, and CIA machinations to oust democratic presidents. In the jungles and mountains of Latin America, U.S. soldiers and diplomats used persuasion, coercion and military force to advance American political and economic interests (though far more in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean than in South America). Much of the current understanding of the topic remains strongly influenced by an especially delicate and painful history of Cold War hemispheric relations.

Yet Washington’s approach then and now has also had instances of cooperation and mutual interest and respect. Riding high on a surge of republican patriotism after the War of 1812, Americans often celebrated Latin American independence on the Fourth of July. Throngs of Americans – not just white males but also blacks and women, northerners and southerners – rejoiced at the advance of Latin American independence, calling the rebels “brothers and countrymen and Americans.” By the early 1830s, more than 200 American children had been named after the liberator Simón Bolívar.

Bolívar’s star-crossed Congress of Panama in 1826 never gained the necessary legitimacy for the Great Liberator’s dream of Pan-American unity, but U.S. policymakers in the late 19th century picked up the slack. Secretary of State James Blaine launched the seminal First International Conference of America States (1889-1890), which were followed by a series of inter-hemispheric conferences and, eventually, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy and then the advent of the Organization of American States in 1948.

U.S. historical engagement in Latin America has been checkered, of course. Critics on the Marxist left saw the Blaine-inspired inter-American conferences and declarations of solidarity as thinly veiled window-dressing for yanqui imperialism. It could also be argued that the U.S became addicted to a series of incredibly costly and ineffective foreign policies, like ultra-orthodox neoliberal policies, the supply-side drug war or unilateral actions such as the 1989 military invasion of Panama to remove strongman Manuel Noriega. Immigration has also always been a hot topic: There is an ongoing bipartisan agreement on deporting illegal immigrants back to Latin America that predates Trump and Miller.

Yet a full historical assessment of U.S. hemispheric motivations and outcomes means we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bath water. The Pan-American spirit has been an integral – albeit imperfect and partially self-serving and paternalistic – part of U.S. regional policies, from the JFK-era Alliance for Progress to the tens of billions of dollars of debt relief authorized by George H.W. Bush in the so-called lost decade of the 1980s to Obama’s swift humanitarian response to the catastrophic 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

In many of these instances, there was a significant, if at times latent, amount of convergence between Washington and Latin America’s aims, especially after the end of the Cold War.

In that sense, Trump has broken the mold. Mutual ideological infatuation with Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro aside, Venezuela is the only salient exception to the distance he has taken from Latin America, recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate ruler in the wake of disputed elections that saw strongman Nicolás Maduro reelected in 2018. Asked by a New Yorker journalist why the Trump administration had involved itself in Venezuela, Trump’s former National Security Adviser John Bolton replied, “The Monroe Doctrine is alive and well. It’s our hemisphere.”

Of course, the most likely underlying reason for this exception to Trump’s isolationist tendencies is political self-preservation: Anti-Chávez and Maduro sentiment still strikes a chord among Venezuela-American and Cuban-American voters in Florida. Trump’s swift move to summarily reverse Obama’s incipient diplomatic thaw with Havana similarly lends credence to this possibility.

Enter the coronavirus

There is an old adage, probably familiar to readers of this publication, that when the U.S. sneezes, Latin America catches the flu. But what will happen with the coronavirus?

Assessing the impact of the pandemic on the hemispheric relationship is fraught, not least because so much depends on the U.S. presidential election, and the inevitable focus on a handful of battleground states such as North Carolina, Florida and Michigan.

Trump’s reelection would almost certainly entail a continuation if not doubling down of the Miller Doctrine. No one knows how long the coronavirus will affect our daily lives, but it seems a safe bet that Trump and Miller will leverage it as much as they can to keep people they deem undesirable from entering the country.

The economic impact of the virus will likely also make Trump seek international scapegoats. Beijing can expect a rough ride, especially with the blame game over what Trump calls the “Chinese virus,” but Mexico may also be vulnerable. Trump is unlikely to tear up the new NAFTA deal (another feather in his campaign cap), but the kind of brinkmanship that saw him threaten President Andrés Manuel López Obrador with rising tariffs could resurface, along with more promises to bring back jobs to the U.S.

The Pan-American spirit’s return would be far more likely if Biden wins, and indeed, Biden’s campaign rhetoric is decidedly in this vein. Biden has said he wants to build on the progress made when he was VP under Obama and reverse the damage done by Trump. In a recent piece for Americas Quarterly, Biden stated:

It is vital that we maintain our leadership role in the region – not because we fear competition, but because U.S. leadership is indispensable to addressing the persistent challenges that prevent our region from realizing its fullest potential.

But Biden will have to confront the red-hot topic of borders – important in 2016, likely to be crucial in 2020. Migration will likely now be perceived as an issue of public health, as much as ideology and economics; being seen as “soft” on Latin American migration may leave Biden open to political attacks along national security lines. Biden has laid the groundwork for a response – stating that “securing our borders, enforcing our immigration laws and fulfilling our humanitarian obligations is a challenging mandate, but we can – and we must – do all three at once.” But Trump’s message is likely to be more strident and showman-like, and potentially galvanizing for swing voters. Another pitfall would be for Biden to heed the yearnings of more radical members of his party in their unpopular and politically myopic push for “open borders.” The same is true of Bernie Sanders’ strident anti-trade integration posture at the very time the hemisphere would be looking to (post-Trump) Washington for leadership on the issue.

If Biden is the victor, he will have the reassurance of knowing that there is an enduring historical legacy behind the broadest outlines of his approach. The risk then would be to assume that since Trump’s Latin America policy was so bad, simply replacing it with a less dysfunctional version would be sufficient. In fact, a rhetorically and ceremonially robust policy is imperative to reassure the region of U.S. dedication to our hemisphere (meaning all of us), not the “our hemisphere” (meaning just the U.S.) invoked by Bolton. Politically speaking, Biden could exploit Trump’s disengagement of the region by pointing out that an unwillingness to help our neighbors and traditional friends opens the door wider for China to traipse around in the neighborhood. And nobody wants that.

U.S. engagement and goodwill – not arrogance and unilateralism, or neglect and ignorance – is necessary now more than ever to deepen constitutionalism and societal reform in Latin America, especially given our current coronavirus reality. Combating the virus may require social distancing, but supporting and safeguarding Latin America from the virus’ long-term consequences is likely to require the hemisphere coming together again, which will require significant commitment and political capital in Washington and throughout the region. But given the economic, health and political complexities the coronavirus is likely to present to policymakers in the coming months and years, if that is achievable is still anybody’s guess.

—

A foreign policy aide to Republican and Democratic presidents and secretaries of defense, Crandall teaches American foreign policy and international politics at Davidson College in North Carolina. His latest book, Drugs and Thugs: The History and Future of America’s War on Drugs (Yale University Press) will be out in the fall. With his co-author and spouse Britta H. Crandall, he is writing a new book, tentatively titled “Our Hemisphere”? The United States in Latin America, from 1776 to the 21st Century (Yale), from which this article is inspired.