MEXICO CITY — President Claudia Sheinbaum rose to power after a decisive electoral victory last June, winning a supermajority in both chambers of Mexico’s Congress. With enough legislative support to push through constitutional amendments, she is actively pursuing reforms proposed by her political mentor, former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. The legacy—controversial in many aspects, such as in the case of the judicial reform— is also set to draw a risky path for the nation’s energy sector.

Days ago, President Sheinbaum enacted the constitutional reform for “strategic areas and enterprises,” which reshapes the nation’s energy sector’s legal framework. In essence, this signifies a major U-turn, reversing the 2013 reform approved under PRI’s Enrique Peña Nieto, which opened the country’s energy sector to private investment. When signing the reform into law, the President expressed her view on the case, stating that the reform is a “very important” change because it “returns to the people companies that always belonged to the people of Mexico and that were privatized in 2013.”

The 2013 reform opened the door to private participation in almost all the value chains in the oil and electricity sectors through market mechanisms, including bid rounds, farm-out tenders and auctions. In a nutshell, back then, the government aimed to create better incentives for state companies to compete and become more efficient while attracting private investment to increase economic growth.

Still, there are several reasons behind this new consequential new reform that could create a complex scenario for private investors. The story of this reform is tied to the political career of López Obrador. A staunch nationalist, he opposed any plans to open the country’s energy sector for many years before becoming President. In 2013, Mexico finally passed a liberalizing reform that López Obrador fought in the streets through protests and later used as a powerful political instrument —accusing the government of privatizing the energy sector— to win the 2018 election.

From the start of his six-year term, AMLO paralyzed the 2013 reform first through administrative measures and later with legislative changes that the Supreme Court eventually declared unconstitutional. With Sheinbaum’s landslide victory, AMLO’s Morena party finally got a chance to dismantle parts of the 2013 reform.

State intervention

The 2024 reform does not preclude private investment participation but reinforces public control and oversight over the energy sector, signaling a broader degree of state intervention. Overall, the reform aims to reassert the “primacy of public interest over private one,” as Sheinbaum has said in the recent past.

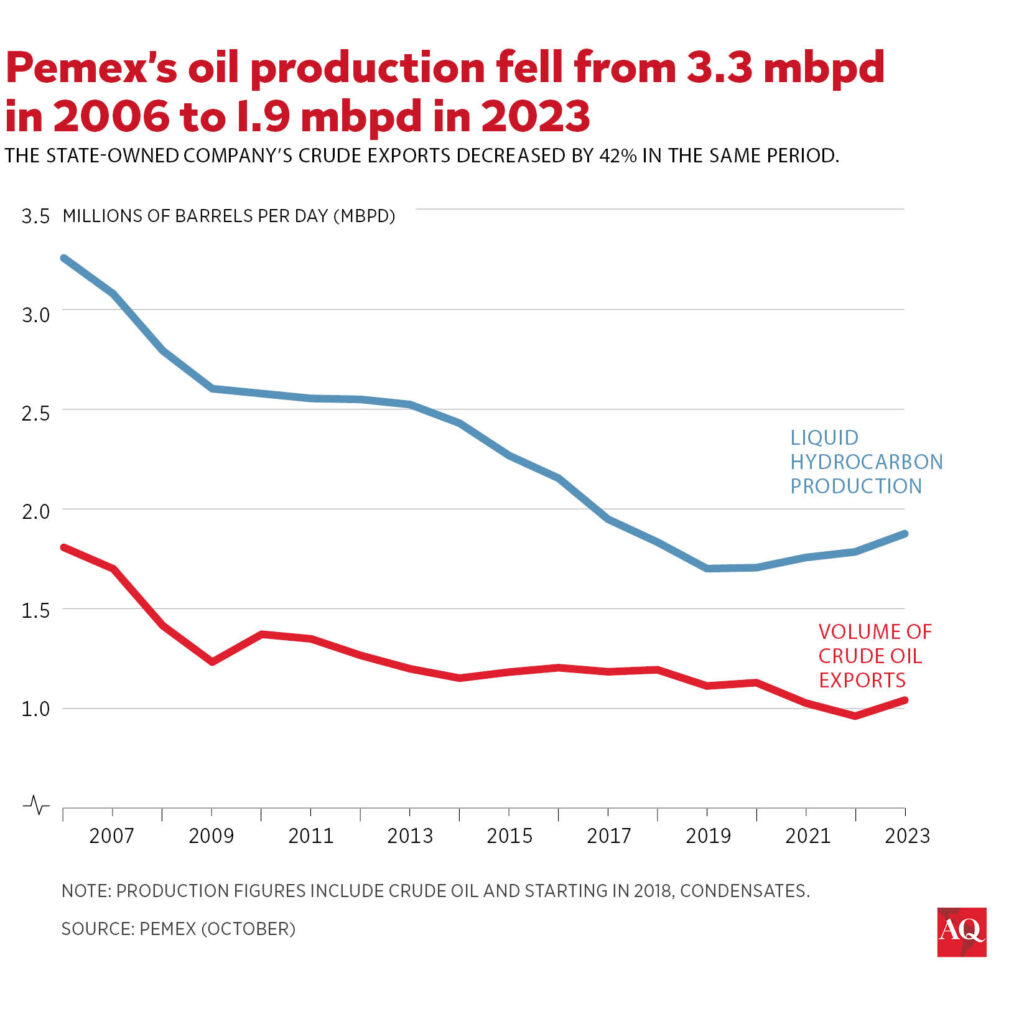

Mexico’s two largest energy companies, Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) and Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), have been reclassified as public state enterprises, emphasizing their role in serving the “public interest.” This happens at a time when both companies face significant challenges. PEMEX’s oil production continues to decline (now below 1.6 million barrels per day) while its financial situation continues to be compromised. Meanwhile, the CFE struggles to provide sufficient electricity nationwide while dealing with low profitability amid subsidies for end users and a costly labor liability.

The reform also clearly states that private activities in the electricity industry will not take precedence over public enterprises. Furthermore, it removes the state’s ability to contract with private entities for energy transmission and distribution, ensuring that public enterprises maintain control over these functions. Lithium, state-provided internet services, and activities conducted by public state enterprises are designated as strategic areas.

A list of concerns

In that regard, the reform raises several concerns, particularly for the business sector. The prioritization of public over private interests, especially in the electricity industry, leaves much space for discretionary decision-making from the government, posing risks for long-term investment. The reform provides state companies with plenty more discretionary power to decide which actors can participate in Mexico’s energy market and how and when they can participate. Furthermore, removing mandates for Pemex and CFE to create economic value and align with international best practices could weaken their corporate governance and enhance state intervention.

By categorizing the activities of public enterprises as strategic, the reform potentially undermines the competitiveness of private companies operating alongside Pemex and CFE. There are no signs that market mechanisms from the 2013 reform will reappear.

The reform will facilitate the vertical reintegration of the CFE – the move to unify several units or subsidiaries –, likely creating a mammoth-style structure, which could lead to less transparency and accountability. In addition, the reform’s move from an economic efficiency criterion for electricity dispatch to one prioritizing the needs of CFE could diminish incentives for investment in generation.

Investor confidence is also at stake. Mexico is already experiencing a disruptive judicial reform, which has raised concerns about the future autonomy of the judicial branch and potential violations of the USMCA trade agreement, which is due for formal review in 2026. Chapters 14, 22, and 29 of the accord, which deal with investment rules and state companies, could be subject to violations.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that Mexico urgently needs to tackle structural bottlenecks in energy capacity to take advantage of nearshoring and increase its low growth potential. Unfortunately, the recently approved energy reform does not respond to the country’s challenges and adds to the current uncertainty. At precisely the time when Mexico needs more legal and economic certainty for market participants in the energy sector, a reform comes along that introduces a range of new problems that could impact investment, competitiveness and the overall direction of the country’s economic policies.

As it has done in recent years, politics has again triumphed over economic efficiency.