In today’s Mexico, concerns abound that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is accumulating too much power, rolling over institutions and putting democracy at risk. Many are calling on the opposition to be more vocal and push back more strongly.

But to have the opportunity to do so effectively, the opposition must first engage in a sincere mea culpa, recognizing its flaws and shortcomings, and acknowledging that the past was not perfect, either. They will also need to overcome the stigmatization they have endured over the last five years—a process in which much of Mexican society participated without properly weighing the consequences.

AMLO swept to power in 2018 by leading a wave of criticism of the country’s political establishment, lambasting traditional parties as part of a mafia del poder. A large portion of society went along with this message, putting all the previous political actors in the same bucket and considering them corrupt, selfish, incompetent and worthless. And now it is precisely those actors that society wants to be brave and ready to fight.

In this sense, Mexico’s is a cautionary tale. Vilifying today’s establishment can mean scrambling to mount opposition tomorrow—a phenomenon that is playing out in other parts of the region, too.

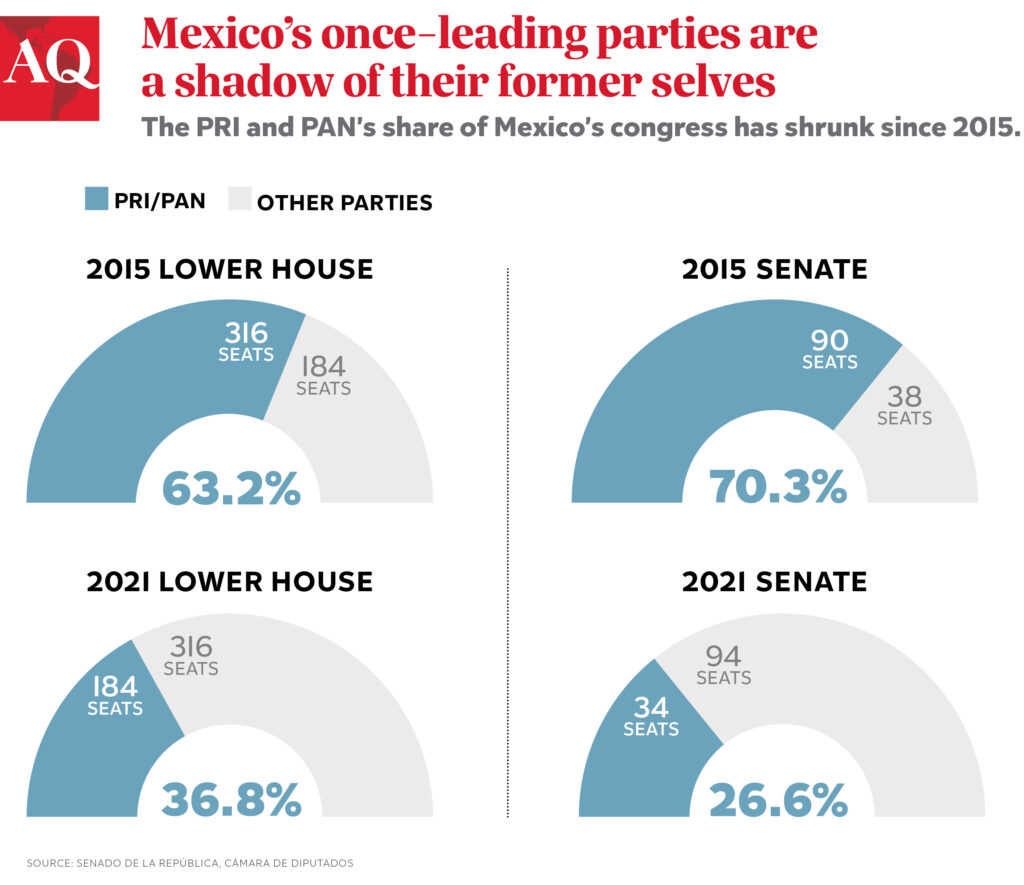

How to move forward? First, the opposition needs to rid itself of the arrogance that has characterized it in recent years and emphasize connecting with voters. The main opposition parties, the PRI and PAN, need to move beyond their internal squabbles, or they will continue to be a shadow of their former selves—the two parties now govern only 11 states, down from 26 in 2017. Although a recent survey showed that 32% of Mexicans have a low opinion of AMLO’s Morena party, the figure for the PRI was 68% and the PAN, 55%.

The opposition must propose a concrete platform for reconstruction and a coherent, shared vision of the future. But they must also be willing to shake off criticism. There should not be shame in accepting that policies can always be improved while insisting that not all political actors are corrupt.

Three years into AMLO’s presidency, Mexico is struggling. By several metrics, inequality, corruption and violence are worse today than back in 2018, when Enrique Peña Nieto’s six-year term ended and AMLO’s began. According to the independent National Council of Evaluation (CONEVAL) the number of those living in poverty has increased from 51.9 million in 2018 to 55.7 million in 2020. As we await CONEVAL’s new figures later this year for 2020-2022, the U.N.’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) foresees the possibility of an additional 2.5 million, which would bring the figure to 58.2 million, the highest level of poverty in the history of the country.

Transparency International saw no improvement in Mexico’s Corruption Perceptions Index in 2021. As the report mentioned, “despite the president’s strong anti-corruption rhetoric, major corruption cases in the country have gone unpunished,” while transparency and good governance have deteriorated significantly. In 2021, more than 80% of government projects were assigned via direct contracts without public bidding, with all the discretion and opacity that this practice entails.

Nor has there been progress in combating violence. During the first two years of the current government’s tenure, Mexico reported 72,000 murders, according to the Executive Secretariat of the National System of Public Security, which compares with 30,572 during the first two years of Felipe Calderón’s administration, and 41,688 during that of Enrique Peña Nieto.

It is clear that the Morena government is failing to deliver on almost every key metric. But yearning for the past is also a mistake to be avoided. The previous government’s technocratic blueprint development—on education, fiscal and monetary policy, energy, state-owned enterprises and governance—was built in accordance with best practices. It still looks good on paper. But we must recognize that it was plagued by problems on the implementation side, including vested interests, lack of transparency, accusations of corruption and politicized policy.

Officials accused of corruption must face justice without delay. But it’s hard to oppose a government whose approval rating remains near 60% when a generalized sense of distrust permeates everyone in public life.

The 2024 presidential election could become a breaking point, as Mexico faces growing inequality, an alarming abundance of arms coming from the U.S., the increased power of organized crime, an already violent environment, and the deliberate deterioration of checks and balances and democratic institutions that should limit electoral excesses and even crimes.

If we want to move beyond polarization and begin constructing a peaceful, more just and successful society that respects diversity, we must be willing to embrace complexity. The world cannot be explained in simple ways—there are always nuances. Constructing a brighter tomorrow requires taking stock of the present and the past with all its achievements and shortcomings.

To provide space for a solid opposition, society must refrain from tarring all political actors with the same brush. Let’s start extricating ourselves from the polarization trap. Why must everything be seen in black and white? Shades of grey are much closer to reality—and reality is a good antidote against a narrative defined by binaries alone.