Argentina | Bolivia | Guatemala | Panama | Uruguay | Full List

See above for a breakdown of Latin America’s other 2019 transitions, and check back here for updates throughout the region’s busy election season.

Election Date: Oct. 20

Format: Two rounds. If no candidate receives at least 50% of votes in the first round, or 40% with a 10-point lead over second place, the two leading candidates will compete in a run-off on Dec. 15.

Evo Morales, 59, president

Evo Morales, 59, president

Movement towards Socialism

“Now Bolivia is a reference for the world. We are not only recognized, but respected. We can’t go back. We must continue.”

How he got here: As the influential leader of a coca grower’s union, in 2006 Morales became Bolivia’s first indigenous president. By nationalizing oil and gas reserves and distributing revenues, Morales’ government lifted millions from poverty. GDP per capita more than tripled under Morales, and his budget surpluses during the good years have insulated Bolivia’s economy against the commodities boom’s end. Since his reelection in 2009, Morales has put pressure on the media and judiciary. A friendly court decision paved the way for him to run in an unconstitutional third term in 2014. Voters rejected a fourth term in 2016, but the top electoral court ruled Morales could run anyway.

Why he might win: Economic and political stability have defined the Morales years. His departure could mean a return to the tumultuous politics that before him saw five presidents in just six years.

Why he might lose: His insistence on staying in power has earned him a reputation as an authoritarian. His friendliness with autocrats in Venezuela and Nicaragua alarms many.

Who supports him: Morales brought Bolivia’s indigenous majority into politics like never before. While his support has waned, many indigenous and rural voters maintain their loyalty.

What he would do: Many fear Morales will seek to govern indefinitely. As Bolivia’s middle class grows, Morales would face the challenge of changing a political platform that appeals mostly to the poor.

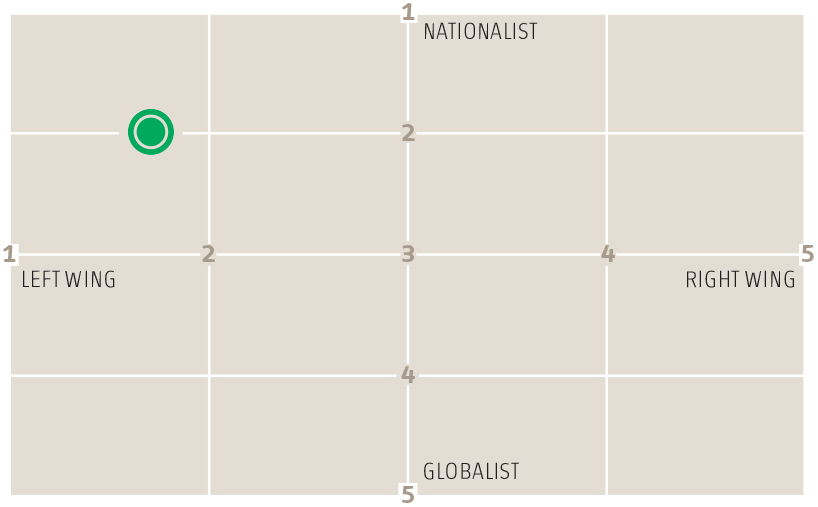

Ideology:

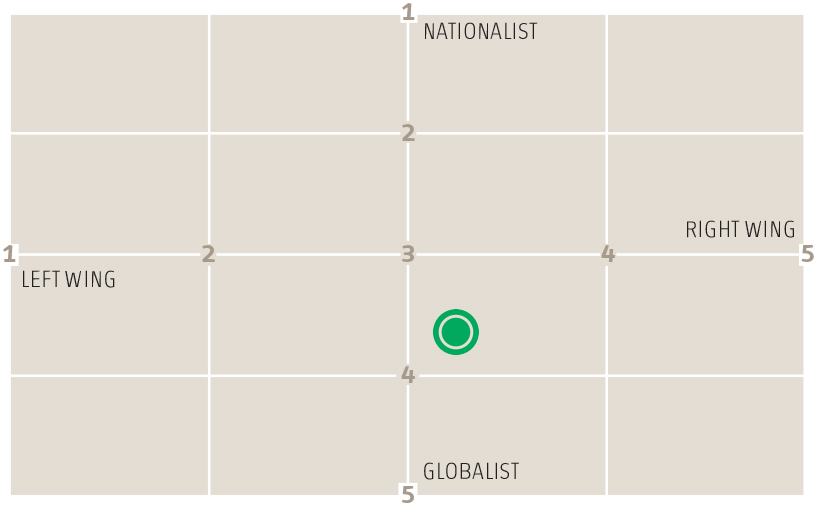

NOTE: AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

NOTE: AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Carlos Mesa, 65, former president

Carlos Mesa, 65, former president

Citizen Community

“The first problem we must confront is that of democracy being destroyed, a democracy that is being built on the image of individual leadership.”

How he got here: Though he served as president from 2003 to 2005, a win for Mesa would be his first national victory. As vice president under Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, he ascended to the presidency after Sánchez resigned amid violent protests over plans to export natural gas. Mesa himself resigned two years later under similar circumstances. A mild-mannered journalist and historian, Mesa later represented Bolivia in its maritime dispute with Chile in the International Court of Justice, a role that bolstered his reputation despite the case’s failure.

Why he might win: Mesa won respect when he broke with Sánchez over the latter’s repression of protesters, and his supporters contrast his intellectualism with Morales’ populism. He’ll benefit from the decision of two former opposition candidates not to run this year.

Why he might lose: Bolivia’s opposition remains divided. Despite Mesa’s efforts to distance himself from Sánchez — in 2018 a U.S. court found Sánchez responsible for ordering a deadly crackdown on protesters — many still associate Mesa with his former boss.

Who supports him: Middle and upper class voters in urban areas and, increasingly, sectors that previously supported Morales, like students and working-class Bolivians.

What he would do: Mesa’s center-right agenda combines free market economics with an emphasis on environmental protection.

Ideology:

—