With Nicolás Maduro facing a federal trial in the U.S., now comes the most delicate phase for Venezuela: making an unexpected political transition work.

As Maduro appeared on Monday in a New York court to face charges of narco-terrorism and conspiracy to import cocaine to the U.S., in Caracas, Delcy Rodríguez, his vice president and oil minister, received approval from the National Assembly to become the nation’s new leader for what is sure to be a tense interim term.

Until Friday, the fate of both politicians was intertwined over years in power, a recast of the Bolivarian Revolution led initially by the late Hugo Chávez Frías. Now, their paths are set to diverge. Maduro will likely face years in prison for alleged conspiracy to smuggle drugs into the U.S. Rodríguez, a lawyer sanctioned by the U.S, the European Union, and Canada for human rights violations and the political and humanitarian crisis of recent years, is now tasked with steering the nation into a new political era, facing an emboldened U.S. that seeks to “run Venezuela” from afar to bring stability to the country.

The question now is whether Rodríguez can avoid Maduro’s miscalculations, and somehow please both the Trump administration and a fragmented, highly volatile political system within Venezuela itself that includes the military, old-guard chavistas, and those pressing for reform.

Photo by XNY/Star Max/GC Images

“Both sides are using each other with different objectives in mind,” Benigno Alarcón Deza, a Caracas-based analyst focused on political transitions, told AQ, explaining Trump’s decision to support Rodríguez’s accession to power. “Rodríguez feels that if she negotiates with Trump, she can buy time to save her head and even the chavista project,” he said. On the other hand, after the demonstration of power and resolution of January 3, the U.S. hopes that some of the most trusted members of the regime “may opt to cooperate, seeking a sort of arrangement or amnesty,” therefore weakening the new government.

Coexistence will be delicate, especially given Venezuela’s failure to follow through on multiple diplomatic efforts in recent years. This includes the Barbados Agreement, which led to the July 2024 presidential election, which the opposition overwhelmingly won, but Maduro chose not to recognize.

Since the start of the Caribbean strikes on September 2, Maduro played the usual script of condemning U.S. actions as imperialistic gestures over natural resources and repeatedly calling for talks between the two countries. He led rallies in Caracas, sometimes dancing and exuding apparent nonchalance, and even held prayer sessions in Miraflores, the presidential palace, to send a message abroad. “Let’s pray for peace in Venezuela,” he said during a meeting with evangelical leaders in November. Amid talks with the Trump administration, Maduro’s hope was to avoid what seemed to be an inescapable end under insurmountable pressure: relinquishing power.

But his efforts didn’t pan out as expected. When referring to Maduro’s fate on Saturday, Trump brought up fragments of his conversations with the now-detained dictator. “I said, uh, ‘You gotta surrender.’ And I actually thought he was pretty close to doing so, but now he wished he did, yeah,” Trump said, without explaining when the conversation took place.

On January 1, Maduro admitted in an interview with a Spanish journalist that he had a 10-minute conversation on November 21 with Trump, who was speaking from the White House. “And it was a respectful conversation—very respectful and cordial,” Maduro said to describe the interaction. That was probably his only opportunity to change his fate, as he put investments in Venezuela’s oil sector on the table for a dealmaking-driven Trump.

On Monday, while pleading not guilty in a Manhattan federal court, the Venezuelan autocrat maintained he was still the “president” of the nation, and a “prisoner of war” who was “kidnapped” from his home. “I’m innocent. I’m not guilty. I am a decent man,” Maduro told the judge.

Delcy’s path

Rodríguez faces a difficult path ahead. “All successions are hard to manage, because they produce infighting among potential heirs. There is bound to be an internal struggle,” Javier Corrales, a professor of political science at Amherst College, told AQ. “It’s too early to tell if her position, and whatever deals she makes with Trump (or not), will be acceptable to some of the important power holders that Maduro himself left in place.”

Rodríguez’s relationships with Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López, a long-term Maduro confidant, and Diosdado Cabello, a hard-core chavista and the interior minister, may need special attention. They control the armed forces and the apparatus of repression, serving as key enforcers of territorial oversight and regime preservation. For now, both have shown loyalty to Maduro’s successor. Jorge Rodríguez, Delcy’s brother, will be her closest ally and political power broker as the president of a new National Assembly inaugurated just hours before she took the reins as interim president.

Rodríguez’s negotiation skills and pragmatism will be key. Venezuela’s vast oil reserves have long played a key role in the nation’s history, and she is expected to play ball with Trump’s demand to see U.S. companies returning to the country.

“She is under high pressure from the U.S. after they captured Maduro; she needs to deliver on their demands fast,” Alejandro Arreaza, an Andean-region economist at Barclays, told AQ. “She is instrumental in facilitating a transitional process, but for now, she does not seem to be seen as a permanent solution.”

Recent actions show Rodríguez’s pragmatism. As oil minister since August 2024, she has been the architect of a recent, modest recovery in oil production. She has operated with apparent ease in securing deals with Russia, Iran, and China, while also preserving Chevron’s presence in the country as the only U.S. company allowed to operate in Venezuela under current U.S. sanctions.

Relations with China and Iran, as well as the “perfect harmony” with Russia, will be on the negotiating table with the Trump administration. The new government will also need to address the fate of 806 political prisoners still waiting for release. Additionally, one day before Maduro’s capture, several media outlets reported the detention of five American citizens.

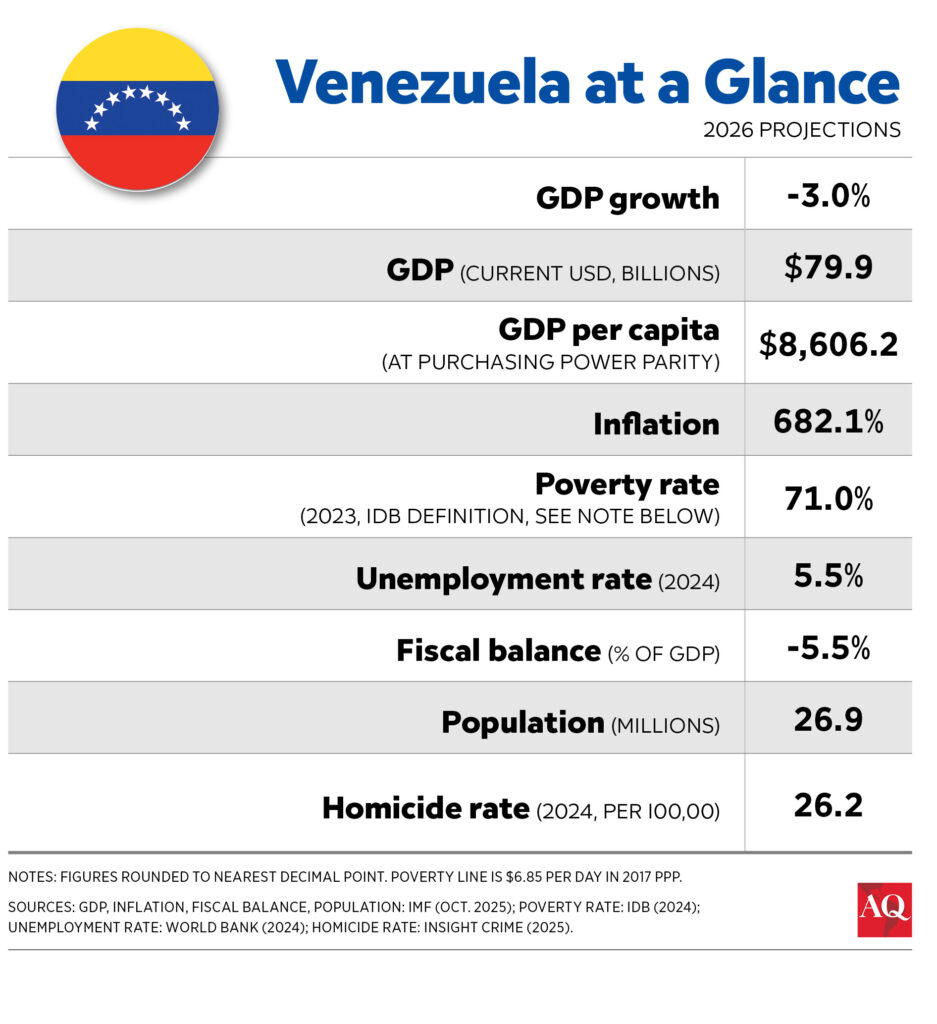

Meanwhile, she’ll need to address an economy on a precipitous decline, with dwindling oil revenues and inflation set to surge once more. “Getting crowned by the Trump administration and the Venezuelan Supreme Court helps, but I do expect some turbulence for her as soon as she starts to make decisions. She may very well come out the winner, but this is not settled yet,” Corrales said.

Without doubt, for Rodríguez, the stakes are especially high. “If she doesn’t do what’s right,” Trump said in an interview published on January 4, “she is going to pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro.”

Trump issued this stark warning as Venezuela enters an unpredictable new era of fragile internal alliances and political redefinitions for an old regime with a new leader, while most Venezuelans hope for a more democratic and prosperous country sooner rather than later.