This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on closing the gender gap | Leer en español | Ler em português | You can watch a conversation with Trajano by clicking here.

In 2017, Luiza Trajano — an entrepreneur who turned a small-town mom-and-pop shop into Magazine Luiza, one of Brazil’s largest retailers — received a dire message from her team: A store manager had been stabbed to death by her former partner, while her eight-year-old son slept in the bedroom.

“It hurt, and I thought to myself, could I have done something? And I pledged that her death would not be in vain.”

Trajano was already a vocal advocate for women’s rights. Four years prior, she had founded a nonpartisan organization, Grupo Mulheres do Brasil, to foster initiatives supporting equal rights and the fight against domestic violence. “I had participated in debates and panels— thought it was an incredibly important topic, but I had never felt it as something close to home,” Trajano told AQ.

Within days of the femicide, her company had assembled an employee advisory group— a committee with lawyers, prosecutors and NGOs working in the field. Magazine Luiza also launched Canal Mulher (Woman Channel), an internal hotline for employees, with trained staff ready to activate a support system, including access to mental health professionals, authorities or legal support — and even relocation when needed.

Getting buy-in from staff was a major priority if Canal Mulher was going to work. “The next day after we created this hotline I was on TV Luiza (the company’s internal live channel) talking to all staff, as I do weekly. And I called on the male employees to help us. The response was incredible,” said Trajano.

“We receive calls from victims’ colleagues, because they know we will not push them to go public or anything, we will just protect them.”

Since its launch in 2017, Canal Mulher has provided support for 420 women, getting them out of danger. “One employee we had to relocate to another state in the middle of the night,” said Trajano.

The next step was to figure out what employees knew about harassment. Leaders and managers across Magazine Luiza were asked to meet with their teams and ask them direct questions: what they thought harassment was, how they felt about it, what kind of workplace they’d like to have.

They garnered 18,000 responses that were then tallied in a report by a research provider, and became the basis for staff training.

“One main finding was that calling (harassment) a joke or ‘just playing’ was very common,” said Trajano. “And we’d ask them, what if it was your daughter?”

The pandemic has sent the project into overdrive, with Magazine Luiza increasing its reach to help customers in abusive households. The company’s app, which counts 26 million registered users, has a button that enables users to call Brazil’s police hotline while pretending to be shopping online.

Trajano said the simple fact that a company has a clear policy can already be a deterrent to criminal behavior. “We had concrete cases of men showing up in stores to harass their partner, but they’ve now disappeared.” And harassment, inside or outside work, is cause for immediate dismissal of employees, something Trajano called “not negotiable.”

While legislation, public policy and law enforcement are needed to combat and punish domestic violence, Trajano’s experience shows that the private sector can play a critical role. And she wants fellow C-suite leaders to take action.

“It doesn’t cost much to maintain a system. I felt like I had to call fellow leaders and show them the importance of a company having an internal tool.” And she did, but kept it a surprise. Invitations for a guided tour of LuizaLabs, the company’s digital innovation arm, were sent to 200 CEOs. “Everyone wants to see the Lab,” said Trajano, smiling.

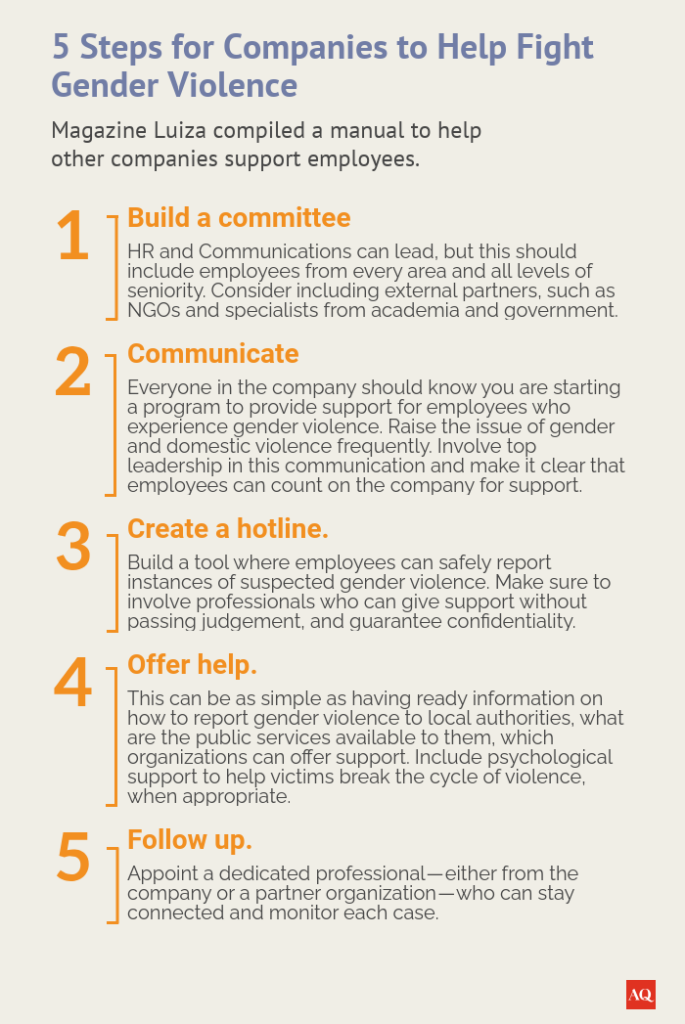

“I invited them for breakfast, but there were also party favors,” said Trajano. The committee assembled to develop actionable initiatives had put together a manual with five steps companies can take to protect their employees. Each CEO received a copy of the manual, and a talk by Maria da Penha, a survivor in honor of whom Brazil’s domestic violence law is named. “But I also did show them the lab,” Trajano said, laughing.

Trajano said taking action is not only a humanitarian issue, but also improves the work environment for men and women, and helps improve the relationship with customers as well. “Since the pandemic especially, people are searching for companies that are socially responsible,” she said.

“And we are available to help,” Trajano offered. “We have helped many other companies in Brazil build their system. We all have responsibility over this.”