RIO DE JANEIRO — Earlier this month, Juliette Dorson, a 50-year-old Haitian caterer, was shot while working an event in Port-au-Prince. Her business partner, Luc, died in the attack. She survived, but barely. For residents of Haiti’s capital, such horrors are tragically routine. Gangs now control four-fifths of the city, wielding not just pistols and assault rifles but sniper rifles and belt-fed machine guns. Few of these weapons are made locally. Most are smuggled from the United States.

Haiti now registers the highest homicide rate on Earth. But the island nation is far from an outlier. Latin America and the Caribbean, home to just 8% of the world’s population, accounts for roughly one-third of its murders. Unlike war zones such as Sudan or Ukraine, the region’s bloodshed occurs in the absence of declared conflict. It is driven instead by organized crime—and by the guns that make violence more lethal.

According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, nearly half of all murders in the Americas are linked to gangs, drug cartels or paramilitaries. In the rest of the world, that figure is closer to one in five. And guns are the weapon of choice. Roughly 67% of murders in the region are committed with firearms—far above the global average of 40%.

From the slums of Port-au-Prince to the favelas of Rio and the border towns of Mexico, criminal groups are heavily armed. Guns are used to enforce drug turf, settle scores, rob civilians, and perpetrate intimate partner violence. Latin America’s “gun culture” spans both the public and the private. Women are disproportionately victims in the latter sphere, with firearms playing a central role in domestic killings and femicide.

The “iron river“

The region has long been awash with American guns. For decades, the so-called “iron river” has flowed southward—legally and illicitly—linking the world’s largest arms market with its most violent region. The legacy of Cold War conflicts in Central America—proxy wars in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua—left behind a glut of weapons. Though disarmament programs were launched in the 1990s, many arms vanished into black markets, feeding the rise of postwar criminal empires.

Colombia became a key hub. Its civil conflict, which spanned half a century, supercharged trafficking networks as guerrillas, paramilitaries and cartels exchanged cocaine for Kalashnikovs. One infamous deal saw 10,000 AK-47s enter Colombia on the back of a falsified end-user certificate in Peru. Another exposed Chiquita Brands International in 2021 for allegedly transporting weapons via cargo ships.

This trade thrives not just on supply and demand, but on systemic dysfunction. Across the region, weapons are routinely diverted from legal to illicit markets. Arms are “lost” in transit, “stolen” from police stocks, or leaked by corrupt officials. In Brazil, federal police uncovered one scheme in 2024—“Cilindro Express”—in which firearms were hidden inside industrial hydraulic cylinders. Another, dubbed “Fiction or Reality,” exposed how traffickers shipped weapons disguised as film equipment via international mail.

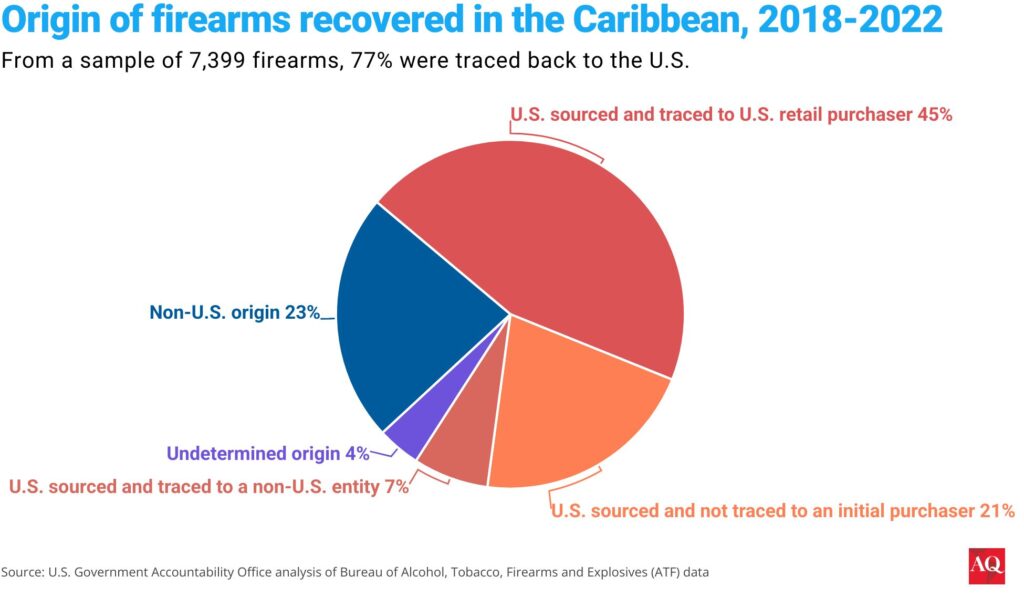

By far the most important supplier is the United States. Between 2018 and 2023, nearly three-quarters of firearms recovered in the Caribbean originated from American states such as Florida, New York and Virginia. The weapons often start their journey in a gun shop or show—legally sold to “straw buyers” who then traffic them south. In some countries, U.S.-made guns are implicated in up to 90% of homicides.

Across southern borders

Mexico is perhaps the most egregious victim. In cities like Tijuana, Juárez and Culiacán, rival cartels battle with military-grade firepower. Tijuana ranked as the world’s most murderous city in 2018 and 2019; Ciudad Juárez claimed that grim title in 2009. Firearms trafficked from the north fuel brutal turf wars between the Sinaloa cartel, Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), and remnants of Los Zetas.

But Mexico is not alone. Across the Caribbean, homicide rates have reached record levels in Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago. Haiti, despite a United Nations arms embargo imposed since 2022, remains flooded with U.S. weapons, often smuggled via the Dominican Republic or hidden in shipments from Miami. Diaspora networks play a key role, ferrying guns concealed in barrels, cars, and air freight containers.

Farther south, countries once considered havens of relative peace—such as Chile and Ecuador—are witnessing a surge in gun crime. The expansion of cocaine routes to the Pacific and through the Amazon has pulled these nations deeper into the orbit of transnational crime. Brazilian, Colombian, and Mexican cartels now operate alongside Balkan and Italian mafias, aided by local officials on the take. Jungle corridors once used to ferry timber and wildlife are now conduits for cocaine and guns.

Criminal groups are also innovating. Emerging technologies—3D printers, encrypted messaging, crypto currencies, drones and even submersibles—are reshaping how weapons are produced, procured, and trafficked. Guns and their components can now be fabricated in-country, complicating law enforcement efforts. Cyberspace has further empowered traffickers, offering anonymity, encrypted logistics, and easy access to global dark markets.

New threats loom. The war in Ukraine, like past conflicts, risks spilling over. According to civil society networks like the Global Initiative on Transnational Organized Crime, military-grade weapons from Ukraine are already circulating across Eastern Europe. Experts worry that some could make their way to Latin America. As with the post-Cold War flood, these arms are at risk of winding up in criminal hands far from the original battlefield.

Defense mechanisms

While the region produces little in the way of firearms, it imports them in abundance—legally and otherwise. Most countries are signatories to international treaties meant to curb arms proliferation, including the UN Firearms Protocol, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and the Organization of American States’ CIFTA convention. Yet compliance is patchy and enforcement weak. Stockpile management is often abysmal, tracing systems underfunded, and oversight of police and military arsenals inadequate. In short, the architecture exists, but the political will is lacking.

Much of the responsibility lies with the United States. Programs such as Blue Lantern (run by the State Department) and Golden Sentry (by the Department of Defense) are meant to track end-users of exported arms. Yet these mechanisms are under-resourced and reactive. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), which oversees domestic gun sales, is hamstrung by outdated laws—not least the 2003 Tiahrt Amendments, which limit data-sharing and traceability.

Still, some countries are pushing back. Mexico is suing American gunmakers for allegedly fueling cartel violence—a landmark case revived by a U.S. appeals court in 2023. Caribbean governments have lobbied Washington to do more to intercept trafficked weapons and tighten regulations on exports. Some U.S. lawmakers are beginning to take notice, proposing reforms to close loopholes in gun laws and bolster ATF enforcement.

Latin American and Caribbean governments are not without agency. They must improve stockpile security, modernize weapons registries, and invest in technologies to trace firearms more effectively. Anti-corruption efforts remain critical. Regional collaboration is essential too. One promising initiative is a 2024 agreement spearheaded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), which brings together 18 countries to strengthen institutions, share intelligence, and bolster cross-border policing.

But progress will be slow and uneven. In a region beset by corruption, weak governance and economic strain, the incentives for traffickers often outweigh the risks. Without robust international cooperation and real pressure on the United States to stem the flow of arms, the river will keep running.

Haiti offers a chilling warning. Years of state collapse, gang infiltration, and impunity have allowed armed groups to outgun the police and overwhelm the government. Port-au-Prince is not a city in crisis—it is a city in free fall. Yet what is happening in Haiti is not unique. It is the logical endpoint of a regional pattern: when institutions are brittle and the guns keep coming, the result is not just violence, but state failure.