By any sober measure, the United Nations just concluded its 80th General Assembly in a defensive crouch. Wars rage from Gaza to Ukraine to Sudan; development assistance is shrinking; climate commitments are slipping; and a once-stable grammar of trade and aid is fragmenting under the pressure of hard power and harder politics. Across Latin America, military buildups accelerate: The U.S. has deployed thousands of marines and sailors to Caribbean waters in what officials call the largest naval presence since the last century, with warships, attack submarines and F-35 stealth fighters positioned from Puerto Rico to Panama. The familiar tableau was on full display in New York: veto paralysis at the Security Council, budget shortfalls across the system, and widening skepticism among publics and leaders who no longer see the UN as guarantor of peace.

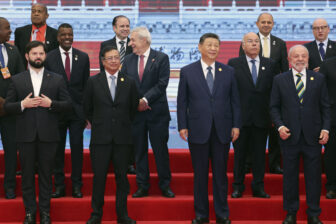

And yet last week showed why the UN still matters—especially for Latin America. Far from the margins, the region stood at the center of the most dramatic confrontations: Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s sharp defense against U.S. tariffs and judicial interference; Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s explosive demand for accountability over Caribbean boat strikes that killed 17 people; Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s $20 billion bailout announcement for Argentina, praising President Javier Milei for laying “the foundations for a new golden age”; and Panama’s steady work at the Security Council, insisting that sovereignty, neutrality and maritime security remain more than slogans.

The UN’s crisis is not primarily about what it does, but whom it serves. For the strong, the UN is optional. For the less powerful, it is oxygen. Take, for example, Trump’s brief backstage encounter with Lula—a conversation of less than a minute that seems to have changed the course of their bilateral confrontation. The U.N. cannot compel great powers to act against their will, but it still provides a venue like no other for smaller or less powerful countries to make their voices heard.

A mirror more than an actor

Critics often indict the UN for failing to stop atrocities or settle wars. But the organization is a mirror before it is an actor. When the permanent five members of the Security Council align, it can act decisively. When they split, the mirror reflects what the world really looks like: vetoes, accusations of bias, and a choked pipeline of mandates, money and legitimacy.

Indeed, for Latin America, last week’s debates were a particularly high-definition mirror. Lula’s moment at the UN podium reflected frustration at economic coercion and judicial interference, warning that multilateralism “is at a new crossroads.” Petro’s extraordinary 25-minute condemnation of Trump—so intense and ridiculous the U.S. delegation walked out—captured mistrust of Washington’s methods and a demand for accountability over what he called the murder of “poor young people” in Caribbean waters. Argentina’s financial drama, culminating in Bessent’s $20 billion package, highlighted both the vulnerability of middle-income economies and Washington’s willingness to intervene for ideological allies. And Panama’s interventions underscored how small states can still use the UN Security Council to spotlight global choke points and defend canal aligned impartiality amid great-power confrontation.

For smaller Latin American capitals, the UN is often the difference between having a platform and having none. The record is clear: Haiti’s stabilization missions, Colombia’s peace verification, the UNDP’s regional development programs, climate funds for Caribbean states, and migration support for hundreds of thousands that crossed the Darién Gap.

This is why debates about “relevance” often miss the point. For Latin America, the question is not whether the UN can compel compliance from a veto-holder; it is whether it can still mobilize resources, command attention, and bring a degree of legitimacy for populations otherwise left to fend for themselves.

Prescriptions for reform

In the quest to enhance or at least protect the UN’s relevance, some nations in Latin America have pursued grand bargains of reform: security Council expansion, an EU single seat, codified veto limits, and others. These efforts remain frozen. While waiting for the ice to melt, the UN should treat reform less as architecture and more as attitude: a bias toward action that delivers for those who cannot turn elsewhere.

For Latin America, three priorities stand out:

Protect the floor before chasing the ceiling. The UN’s most prosaic functions—food, health, schooling, election support—are also its most defensible and most needed. When budgets contract, these are too often the first targets. Instead, a financing floor for humanitarian and development programs should be locked in.

Build coalitions of the willing—and the small. Great-power consensus is scarce, but coalitions of middle and small states can matter. Latin America has led before: Costa Rica on arms trade, Chile on human rights, Caribbean states on climate. Panama, with its canal and Security Council seat, is well-positioned to convene initiatives on maritime security and infrastructure transparency.

Measure outcomes, not communiqués. The UN is awash in reports; what it needs are receipts. Dashboards tracking migrants processed, hectares of Amazon preserved, gang violence curbed in Haiti or climate projects completed in the Caribbean would show taxpayers and donors that the system delivers.

Much public disillusionment with the UN rests on charges of bias. The corrective is not silence, but precision: clear principles, transparent methods, impartial accountability. Panama’s Canal neutrality treaty offers a model, balancing U.S. partnership with independence. The UN, too, must show that neutrality does not mean paralysis, but survival through credibility.

The UN’s finances remain skewed: overreliance on a handful of donors, arrears from major powers, politicized conditionality. Pragmatic steps can help—widening the donor base, normalizing multi-year humanitarian compacts, embedding private co-financing. For Latin America, this is not abstract. Argentina’s bailout showed how development finance can be lifeline or political weapon. UN programs provide alternatives when markets wobble or great powers pick favorites.

At eighty, the UN is not the world’s conscience or police force. It is the survival institution: the place that convenes everyone and, on the margins of impasse, moves enough resources, expertise and legitimacy to matter—especially where little else does.

The great powers will decide when to stop fighting. Until then, Latin America needs an institution that knows how to keep people coherent while they wait. Last week at UNGA, our region made clear it will not wait quietly. This is not the romance many of us grew up with, but it is not nothing. In an era when the powerful double down on their own instruments—alliances of convenience, mini-lateral clubs, transactional bargains—the UN will not die from irrelevance. It must be kept alive by necessity, until the world order settles again. It needs humility and a politics of enough—enough diplomacy, enough food, enough schooling, enough safety, enough restraint—to keep fragile places from becoming dangerous ones. For Latin America, that is not idealism. It is survival.