This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on the politics of water in Latin America | Leer en español

MEXICO CITY — Delivering water in Iztapalapa for the past 13 years has put Jesús Martínez on the wrong end of a gun barrel more than once.

Sometimes when the taps run dry in this hardscrabble borough at the heart of Mexico City’s water crisis, desperate residents — or thieves on the make — reroute tanker trucks at gunpoint to meet their needs.

“It’s basically a kidnapping,” Martínez told AQ.

Others illegally tap wells outside the city and fill unregulated tankers themselves. Stolen water of dubious quality can serve neighborhoods in need or be sold at a premium to meet demand, especially during a drought or when the city’s system is under repair.

Even under normal circumstances, water service in Iztapalapa is a contentious issue. Almost 15% of the borough’s 1.9 million residents say they lack regular access to piped water. In the city as a whole, the figure is around 10%. At the Germanio housing unit, where Martínez was recently sent for a delivery, residents complained of their water being shut off for months on end.

Part of the problem is geography. Water enters Mexico City from the west and loses pressure as it makes its way through the borough’s eastern sprawl. Soft, shifting ground soil means pipes are prone to break and difficult to maintain. Chaotic growth, especially in the form of irregular, off-the-grid communities, has made matters worse. The metropolitan area of over 21 million people has grown by around 100 square miles since 2010.

“Having this pressure on the water system puts people’s lives at risk,” Jorge Arriaga Medina, executive director of the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s water research network, told AQ. “And low-income communities are the most vulnerable.”

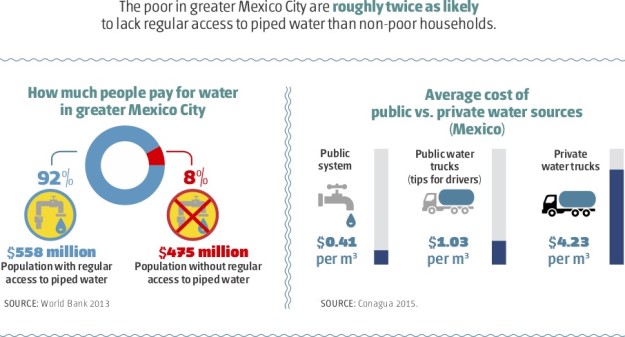

Indeed, throughout Latin America and the developing world, it’s the poor who pay the highest price for water scarcity and mismanagement. Low-income, especially rural families, are the least likely to have regular access to public water systems, meaning they sometimes pay 10 to 20 times more for water in absolute terms than their rich counterparts, according to the UN.

Free government-provided filling stations offer some relief, but not enough to cover residents’ needs.

Free government-provided filling stations offer some relief, but not enough to cover residents’ needs.

The water that does reach poor communities is often untreated or of low quality, driving the health problems that make poverty that much more difficult to overcome. Regionwide, waterborne illness impacts thousands of people every year. In Mexico, tainted water is the number one killer of children between ages 1 and 5.

The public tanker service that provides many residents in Iztapalapa with water to shower, wash dishes and prepare food is offered free of charge. But families that rely on it conserve and reuse much more than their share. While rich neighborhoods in Mexico City consume between 800 and 1,000 liters of water per person per day, poor neighborhoods use just 28 liters, according to a report from the city’s human rights commission.

Even as poor communities conserve what little they have, the aquifer that provides Mexico City with more than half of its water is being drawn down twice as fast as it’s being replenished. At the current rate, experts say it could hold out for about 40 years.

But the city’s water drama has already begun.

Makeshift pipes

The bundles of black cable that crisscross the streets of Tierra Colorada look like the overhead TV and electrical wiring seen in much of Mexico City, until you hear the water trickling inside.

A community of mostly informal houses clutching the side of the Ajusco volcano, Tierra Colorada is home to one of Mexico City’s most complex public policy challenges — and a different kind of irregular water use.

Few, if any, of the 2,000 or so families living here have access to the public system, and much of the neighborhood is inaccessible to tanker trucks. Previous governments started building infrastructure to provide piped water about a decade ago, but residents say they’ve never seen a drop. (That hasn’t stopped some from receiving bills for the service.)

Hanging tubes carry water to most Tierra Colorada residents.

Instead, residents in Tierra Colorada rely on a self-installed system of tubes to draw water from makeshift wells dug a mile or more up the mountain. Organized groups contribute money and manpower to maintain the wells, pipes, cisterns and faucets that provide their homes with enough to get by.

“The little that comes out we have to be careful with,” resident Alicia Cruz told AQ. “In the dry season, I use the same water two or three times to wash clothes, and then I use it again for the bathroom.”

Ajusco means “where water blooms” in native Nahuatl. But changing weather patterns have even made bootlegging more difficult. Hiking up the mountain to clean his group’s well one recent morning, Angelo Guzmán pointed out dry gullies that in normal years would have overflowed with water. The well itself was little more than a muddy puddle around his boots.

“If it doesn’t rain this month, we’ll be out of luck,” Guzmán said. “We’ll have to go flirt with the mayor.”

Emergency response

Of the 311 liters per person that enter Mexico City’s water system on a given day, around 134 go unaccounted for — lost to leaks, theft or unregulated taps. Officials say if they could just reduce the amount being lost, it would go a long way toward reducing daily water stress.

Past administrations have put money into new infrastructure but failed to invest sufficiently in technology to help them understand the system and quickly find and repair leaks, Arriaga said.

There’s hope that may change under Claudia Sheinbaum, an environmental scientist who became mayor last year. She and the head of Sacmex, the city’s water authority, say that improving real-time monitoring of the system is a top priority. This year, Sacmex’s 6 billion peso ($300 million) budget is twice what it was in 2018.

The new administration is also working with a local NGO on plans to install 10,000 rainwater capture units in Iztapalapa and elsewhere by the end of the year.

But in the meantime, service continues to falter. In September the government reduced water pressure for much of the city due to lack of rain, again making theft — and finding water — an urgent concern.

“Nobody is going to oppose the idea of water as a human right,” said Arriaga. “But making that a reality is something else entirely.”

—

Russell is a senior editor and Mexico City correspondent for AQ

All photos by Alicia Vera