This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s election super-cycle

A group of men and boys pull at a fishing line on a beach on Margarita Island, off the Venezuelan coast. One man seems to pull harder than the rest, shorts and shirt sleeves rolled tight as he strains against the tension of the rope.

This image, at once modern and enduring, greets visitors to the Getty Center’s exhibition on the life and work of Alfredo Boulton—a testament to what he called the “exuberant beauty” of the Venezuelan people.

Taken in the 1940s and entitled Faenas del mar, the photo is representative of Boulton’s aesthetic contributions to Venezuelan art in the 20th century. In the decades after his birth in 1908, Venezuela became a center of modernity in the Americas thanks largely to a booming oil industry. Boulton chronicled his country’s transformation on film, photographing people, landscapes and practices, in many cases for the first time.

Alfredo Boulton: Looking at Venezuela, 1928-1978 makes clear that his influence extended far beyond the camera lens. Indeed, few figures have exercised the level of influence over the development of a country’s art and art history that Boulton did, even though he is little known outside Venezuela.

“Boulton is an amazing modern photographer, but he is someone who goes beyond that,” said Idurre Alonso, the curator of Latin American collections at the Getty Research Institute. “The big discovery for me was to understand how important he was in formalizing art history in his country.”

Alfredo Boulton: Looking at Venezuela, 1928-1978

Getty Center, Los Angeles

On view until January 7, 2024

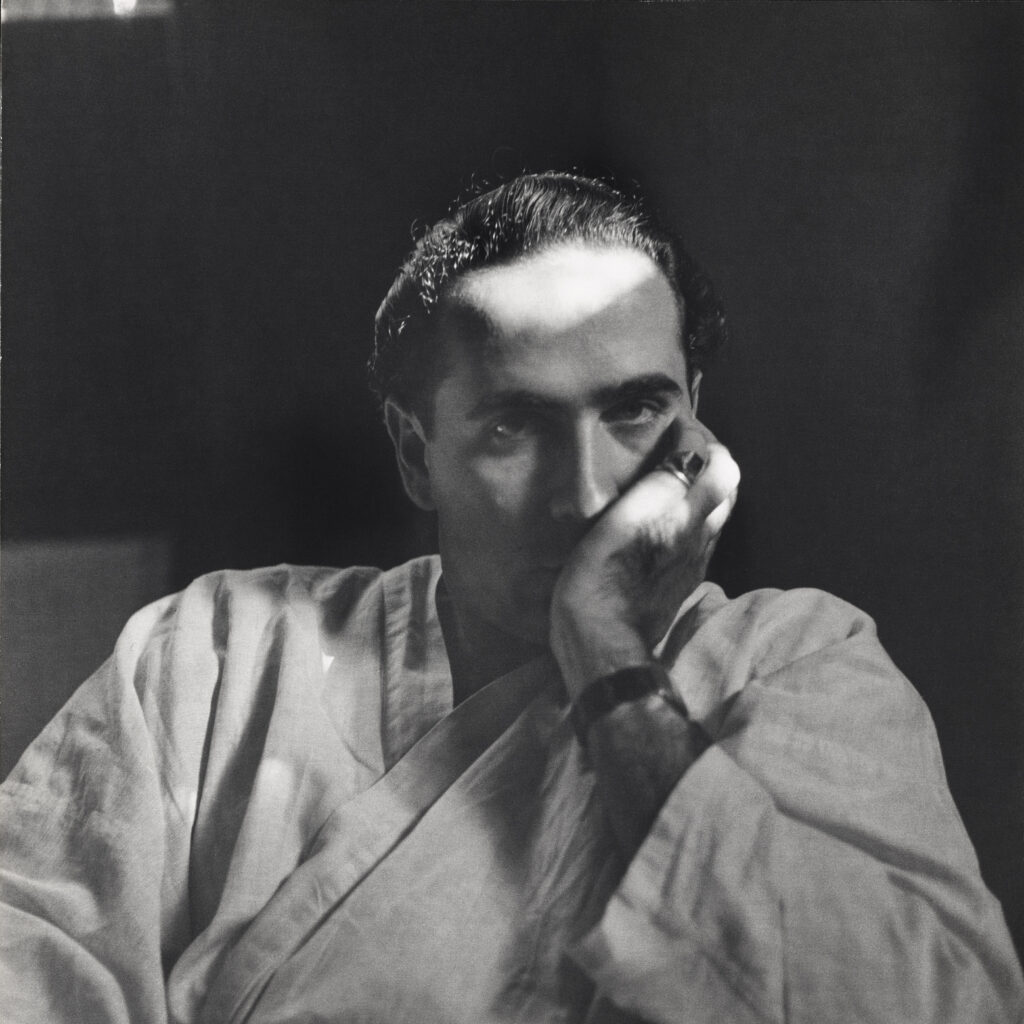

Made possible by the Getty’s acquisition of his archive in 2018, the exhibition uses photographs, correspondence, albums, videos, papers and other material to point to who Boulton was both as an artist and as a man.

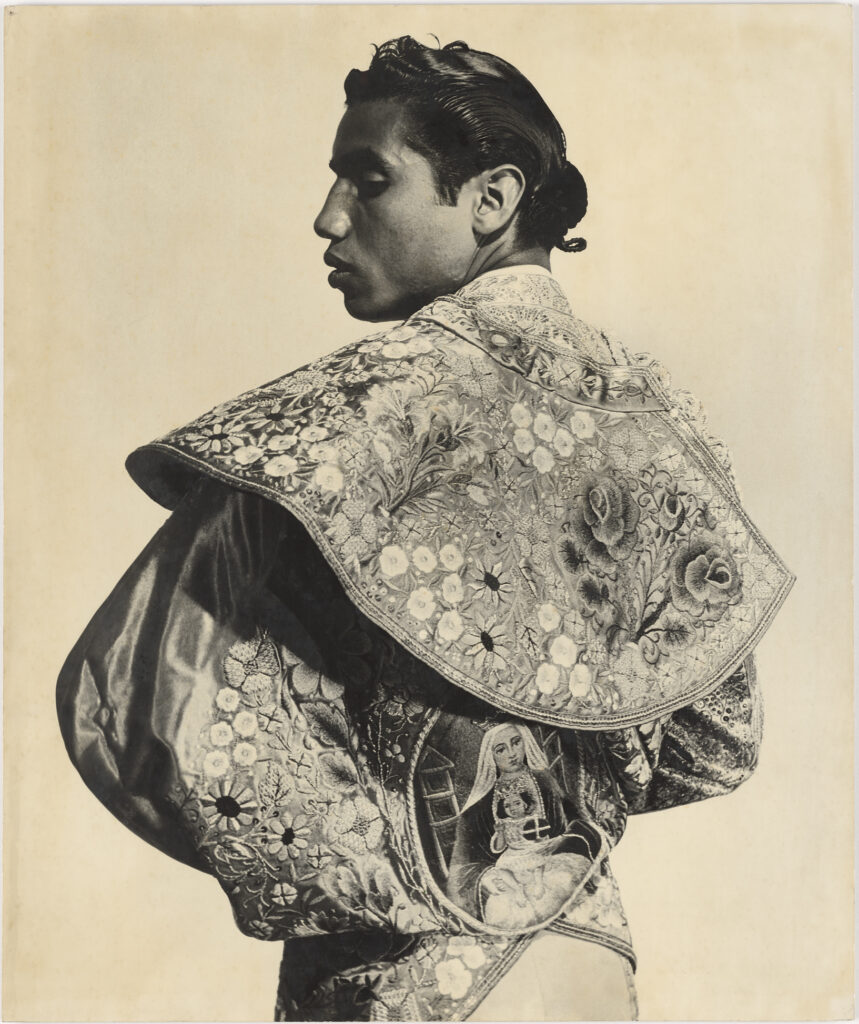

Born to a wealthy family in Caracas, Boulton was educated in Europe, influenced by Man Ray and other avant-garde figures. But many of the photos on display show Boulton’s fascination with the land of his birth and its modern traditions. Margarita Island and the Venezuelan plains feature prominently, as do evocative portraits of men and women at work and play. One particularly striking image shows the bullfighter Luis Sánchez Olivares in profile, an elaborate traje de luces draped over his shoulders. In another, Boulton’s wife Yolanda poses as the Roman goddess of flowers and spring.

The exhibition also recognizes Boulton’s contributions as a historian and advocate for Venezuelan art and artists. He documented every era in his country’s artistic history, dating back to pre-Hispanic pottery, and in his lifetime published some 60 books, all while supporting and organizing exhibitions for friends and fellow artists such as Alejandro Otero and Jesús Rafael Soto.

Included too is Boulton’s personal life, with reproductions of his furniture, wall-sized photographs of his home on Margarita Island and screenings of films he took on trips to the plains and elsewhere. A book of collected essays accompanying the exhibit delves deeper into his life and legacy.

“In the book we talk about his importance but it also gives us the opportunity to have a critical lens in the way we approach his work,” said Alonso, who edited the collection. “There’s a lot of things he covered and lot of things he didn’t cover in terms of his historical research, for example.”

By 1970 Venezuela had become one of the richest countries in the world, and while Boulton had done much to document its modern transformation, his gaze was at times incomplete. Still, however idealized his vision of the Venezuelan archetype depicted in photos such as Faenas del mar might have been, few figures did more to document and formalize Venezuelan art and art history—and as the Getty’s impressive exhibition shows, we are all better off for it.