After her election in 2021, observers had high hopes for Honduran President Xiomara Castro—and much skepticism. Now, a year and a half into her administration, Castro has increased government spending and sought investment from China. But other campaign promises remain unfulfilled, and Castro’s LIBRE party is divided.

Crime remains high, helping fuel enormous, continued flows of northward migration. All this is taking a toll on Castro’s approval, which dropped nearly 20 points over the past year to 43%, according to a recent survey. But despite these serious problems, Castro has been safe so far from a severe breakdown in support—in large part because of the remittances sent back by Hondurans abroad.

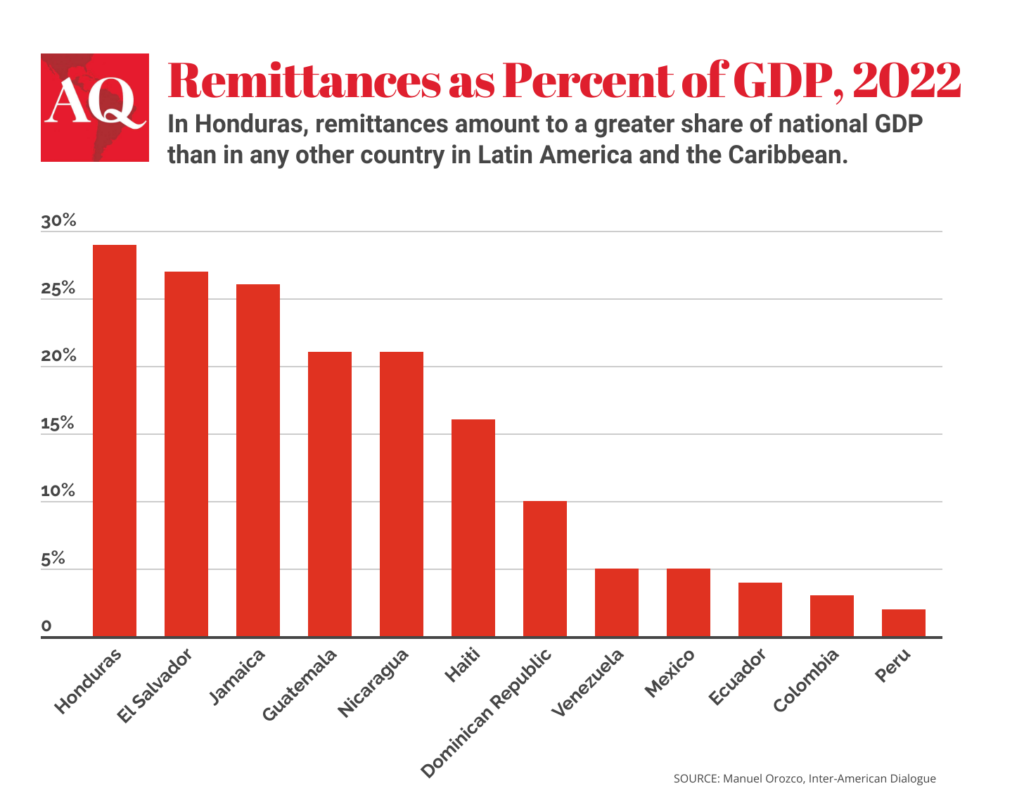

Honduras is the Latin American country that most depends on remittances, which make up almost 29% of its GDP. In ten years, from 2012 to 2022, the flow of money has almost doubled. This provides the country with an economic lifeline, supplying the government with hard currency reserves and allowing families to pay for food, shelter, medical care and education. But they also remove much of the incentive for the government to provide basic services or combat the root causes of migration, such as crime and a lack of opportunity at home. This “remittances trap” keeps Honduras, and its government, on life support—but at a steep cost.

Trapped by remittances

After pledging to establish a UN-backed International Commission Against Corruption in Honduras, Castro’s administration has not yet done so, despite a trip to New York last December assuring interest remained strong. Meanwhile, as neighboring El Salvador continues a crackdown on gangs, Castro has expanded the role of the military in security roles, allowing them to patrol certain areas and impose curfews, leading some to worry about the integrity of constitutional guarantees and human rights violations. Domestic and international organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have also raised concerns over whether Honduran prisons can withstand an increase in arrests.

On the foreign policy front, Castro cited economic motives for her decision in March to cut diplomatic ties with Taiwan in favor of Beijing. Chinese trade in Central America has grown over the past few years, and the government is seeking investments in a potential hydroelectric dam, and other infrastructure projects. Castro argued the move would help push forward the growth of the Honduran economy and also reduce migration.

Meanwhile, a flood of Hondurans continue to leave the country, which increases the flow of remittances to those who stay behind. The Migration Policy Institute estimates nearly half a million unauthorized Hondurans resided in the U.S. as of 2019, equivalent to roughly 5% of the population of Honduras.

According to Inter-American Dialogue data, remittance recipients represent close to half of all households in Honduras. The continuous flow of remittances acts as a safety valve that alleviates the socio-economic pressures that drive individuals to migrate—but only in a superficial way. As a result, the government lacks a strong incentive to tackle comprehensively the root causes of migration. The remittance trap perpetuates a cycle where migration remains a steady outlet for the population seeking better opportunities abroad, rather than investing in creating those opportunities at home.

Remittances help sustain private consumption—and for many families, they represent the only source of income. Since Honduras is so heavily dependent on imports, remittances also help mitigate inflation and keep prices somewhat low for basic imported goods.

But the trap lies in receiving large inflows of foreign exchange without increasing productivity levels, or adding jobs in sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, tourism—or training a more skilled labor force and strengthening the knowledge economy, which would be central to creating growth and mitigating migration.

What are the drivers of migration from Honduras? One of the main culprits, as in many countries that register alarming levels of migration, is the large informal economy, where over 70% of the labor force and private sector contribute only 20% of GDP. For those who can’t make ends meet in informal employment and have few chances to enter the formal labor force, migration is a last-ditch option. Most families are also already connected through remittances to someone they know that has migrated.

Crime, homicide, extortion and violence against women are push factors, too, as well as climate change. Being unemployed increases the chances of becoming a migrant, and youth unemployment is near 20%, with the majority of the population in Honduras still under 40. This demographic is also the most likely to migrate. The pandemic and hurricanes have hit the Honduran economy hard, creating losses of jobs and savings.

How to make remittances count

The best way to maximize remittances’ positive effect on the economy is leveraging them for savings and credit through financial institutions. Since remittances boost disposable income, they can increase savings. But because close to 50% of Hondurans are unbanked, it’s hard to close the gaps and drive job creation.

Remittance recipients are more often women, but they lack financial independence. A differentiated approach regarding gender would be important as part of a potential national program for people to put their savings in banks or credit cooperatives. The Honduran government should focus on developing tools that motivate and attract recipients to access and use the financial products that will allow them to increase their assets, thus generating a sense of ownership and belonging.

For the time being, Honduras seems to be trapped in a bad equilibrium, where the costs of voicing opposition to state incapacity have become higher than opting out by migrating. So long as Hondurans’ demands for a better social contract go unheard, further outward movement will be the result.

—

Kawas is senior associate for the Migration, Remittances and Development Program at the Inter-American Dialogue and a Wilson Center fellow.