A leader in exile—or, according to the government, on the run from justice. Top cadres in jail or scattered across continents. A society still nursing the wounds of a decade of polarization.

These are not exactly the makings of a political comeback. But don’t tell that to Ecuador’s left-populist ex-President Rafael Correa and his supporters. Fresh off legal and electoral victories, correísmo is on the cusp of once again winning national office.

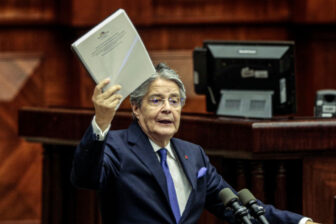

On May 17, Correa and his supporters got the news they had been waiting for: Ecuador’s embattled conservative President Guillermo Lasso declared muerte cruzada, dissolving the National Assembly to dodge an impeachment vote he seemed bound to lose. According to the constitution, Lasso will now govern by decree for up to six months as the country votes in snap general elections. A correísta victory is not a guarantee—but it’s probably the most likely outcome.

As badly as Ecuador needs change, there are signs correísmo is not fully prepared to chart a new path. Party leaders’ vision of the country and its problems seems stuck in the late aughts, when Ecuador enjoyed sky-high commodity prices, easy access to Chinese credit and low crime rates. It’s anyone’s guess how they would contend with new challenges: Ecuador’s surge in criminal violence and tightening global financial conditions. Above all, Rafael Correa still calls the shots—and does not want to run the risk of losing power again. If he returns to the country, the recent rise of “moderate” correísmo could come abruptly to an end.

Losers on a Winning Streak

Until a year or two ago, correísmo was out of luck. After Correa left office in 2017, his hand-picked successor Lenín Moreno broke ranks almost instantly, purging Correa loyalists from state institutions. New judicial authorities launched sweeping corruption investigation against Correa and his allies, which the latter argued was a form of “lawfare.”

Several party leaders went to jail. Others scattered across Latin America and Europe. Correa took up residence in Belgium to dodge a corruption conviction he claimed was baseless. The 2021 elections were a low point, with correísmo‘s candidate falling short of expectations in the run-off against Lasso.

But then Ecuador fell to pieces. Amid rising hunger, a moribund economy and the worst violence in the country’s history, Correa’s movement and his rebranded Citizen’s Revolution (RC) party has been on a winning streak. Former Correa government officials Jorge Glas and Alexis Mera were released from prison in recent months—allegedly, as the result of a deal with Lasso, although Lasso denies this. More convictions could be overturned soon—and it’s not just legal battles that the correístas are winning: They have also racked up recent electoral wins.

In February, RC candidates gained control of twice as many city halls as any other party in local elections, winning in Quito, the capital, and Guayaquil—Ecuador’s largest city and a longtime bastion of conservative anti-correísmo. Correístas even claimed victory in the province of Azuay, the heartland of Indigenous opposition to correísmo. True, most of these mayors won over a fragmented field. But in Ecuador’s weak party system, being the least weak is enough.

Now, correísmo stands to gain more than any other force from early elections. No wonder Correa greeted Lasso’s declaration of muerte cruzada as an “opportunity,” and party leaders celebrated the news on the steps of the assembly—even as it cost them their jobs.

Correísmo 2.0?

The results of the recent local elections—in which correísmo ran moderate candidates and did well—seemed to signal that a gentler and kinder correísmo had emerged out of the party’s years in the wilderness.

There is a grain of truth to that. Lately, RC looks more like a big-tent party of the left willing to branch out beyond its old model—statist developmentalism heavy on extractive industries and redistribution but light on protections for the environment, Indigenous communities and women and sexual minorities.

Pabel Muñoz, the newly elected mayor of Quito who comes from the party rank and file, recently supported a grassroots environmental movement. Correísta insiders I interviewed for this piece expressed a desire to “transcend extractivism” and turn Ecuador into “the Dubai of clean energy.”

On social issues, many correísta leaders have also rethought their social conservatism even as Correa himself hangs on. Marcela Aguiñaga, a correísta official in Guayas who once echoed Correa’s socially conservative views, has lately reinvented herself: “We are going for the youth vote, the feminist vote and the environmentalist vote,” she recently said. Last year, the party let its lawmakers vote their conscience on a bid to decriminalize abortion in cases of rape.

Correísmo 2.0 could also be more moderate economically. There seems to be consensus that the next correísta government cannot spend without limit and take on huge debts, as in the past, and must instead make do on a tighter budget. On foreign policy, correísta leadership yearns to pull away from Washington and take up the non-aligned stances characteristic of Latin America’s other recently elected leftist presidents. They believe Ecuador is missing out on a chance to exploit the reshuffled world order and deepen ties with other Latin American countries.

Returned to power, correísmo is likely to adopt social and economic policies closer to those of Gustavo Petro than those of Nicolás Maduro—or Correa 1.0. But when it comes to democratic institutions, it’s another story. There does not seem to be much willingness to reckon with the past. Asked about the illiberal tendencies of correísmo 1.0, correísta leaders and figures close to the party I interviewed occasionally acknowledged “excesses”—a polite term for the espionage and press censorship of Correa’s previous governments. But there did not seem to be much appetite for reconciling with political rivals or correísmo’s critics in civil society—especially after what many in the party view as years of persecution and exclusion by these forces.

Correa has not hid his ambitions: As recently as last month, he said he intends to call a constituent assembly and replace the 2008 constitution that he himself helped craft. Constitutional replacement would purge the state bureaucracy and dismantle checks on executive power. Wiping clean Correa’s and his allies’ judicial records is another top priority—one that requires control of the judiciary. While Brazil’s Lula da Silva and Colombia’s Petro took office offering olive branches to their former rivals, Correa appears to be in no mood to forgive and forget.

Most concerning is Ecuador’s explosive surge in organized crime. It’s not clear that Correa and his party have much of an answer beyond restoring their old security policy: increased social spending and—perhaps—a return of the non-confrontational approach to drug trafficking that characterized correísmo 1.0. It’s unlikely that recipe will work to pacify Ecuador’s new criminal landscape, which is better financed, better organized, and more willing to coopt—or if that doesn’t work, attack—state officials than before. With top military brass having sided openly with Lasso in the current showdown, and the police and Correa historically at loggerheads, it’s also reasonable to forecast friction between security forces and a new correísta government.

There’s a chance correísmo does evolve in a more moderate, democratic direction. But it’s a slim one.