Bolivia’s current president, Luis Arce, was Evo Morales’ economy and finance minister for 11 years, stepping down only to seek treatment for kidney cancer. Together, at the head of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, the pair presided over Bolivia’s “economic miracle” of the 2000s and early 2010s, slashing poverty and quadrupling GDP as they rode the region’s commodity boom.

Those days are long over. Today the two leaders are wrestling each other for control of the MAS and its nomination for the October 2025 presidential election, a bitter and highly personal battle that is taking a visible toll on Bolivia’s economy and overall stability.

For now, Arce appears to have the upper hand, analysts told AQ. But the rivalry has already stalled critical legislation in a divided Assembly and provoked drawn-out, costly demonstrations. This is limiting Arce’s ability to address the U.S. dollar shortage that has hounded the economy for over a year, jeopardizing subsidies and anti-poverty programs, sparking protests, and leading Fitch, Moody’s and other ratings agencies to downgrade Bolivia’s bonds to junk status.

And there’s no end in sight. It’s not clear whether the MAS will hold primaries or even which camp formally controls party leadership; a high court is set to weigh in on the latter question imminently. Whatever the ruling, it’s likely to raise the temperature of a conflict that has already spilled into the streets. Anti-government demonstrators protested shortages of fuel and dollars on May 17, promising future disruptions; teachers demanded higher salaries in a rally in La Paz in April; and Morales supporters blocked roads for two weeks in February to protest court decisions favoring Arce’s claim to the MAS, causing sizable economic losses.

“The political situation is going to be very intense given the social movements from both sides of the party that are threatening major mobilizations,” said María Teresa Zegada, a sociologist at the University of San Simón, Cochabamba, and a researcher with the Center for the Study of Economic and Social Realities (CERES).

Infighting and institutions

The MAS, founded in 1997 by Evo Morales and other campesino grassroots leaders, continues to dominate national and local politics. When Arce ran for president in 2020 as the technocratic successor to Morales’ larger-than-life figure, he won convincingly with 55% of the vote, well ahead of centrist Carlos Mesa (28%) and conservative Luis Fernando Camacho (14%), the governor of Santa Cruz who has been imprisoned and awaiting trial since December 2022 on charges stemming from Bolivia’s 2019 political crisis. For his part, Morales is trying to stage a comeback after being ousted in 2019 for his controversial attempts to secure a fourth term as president.

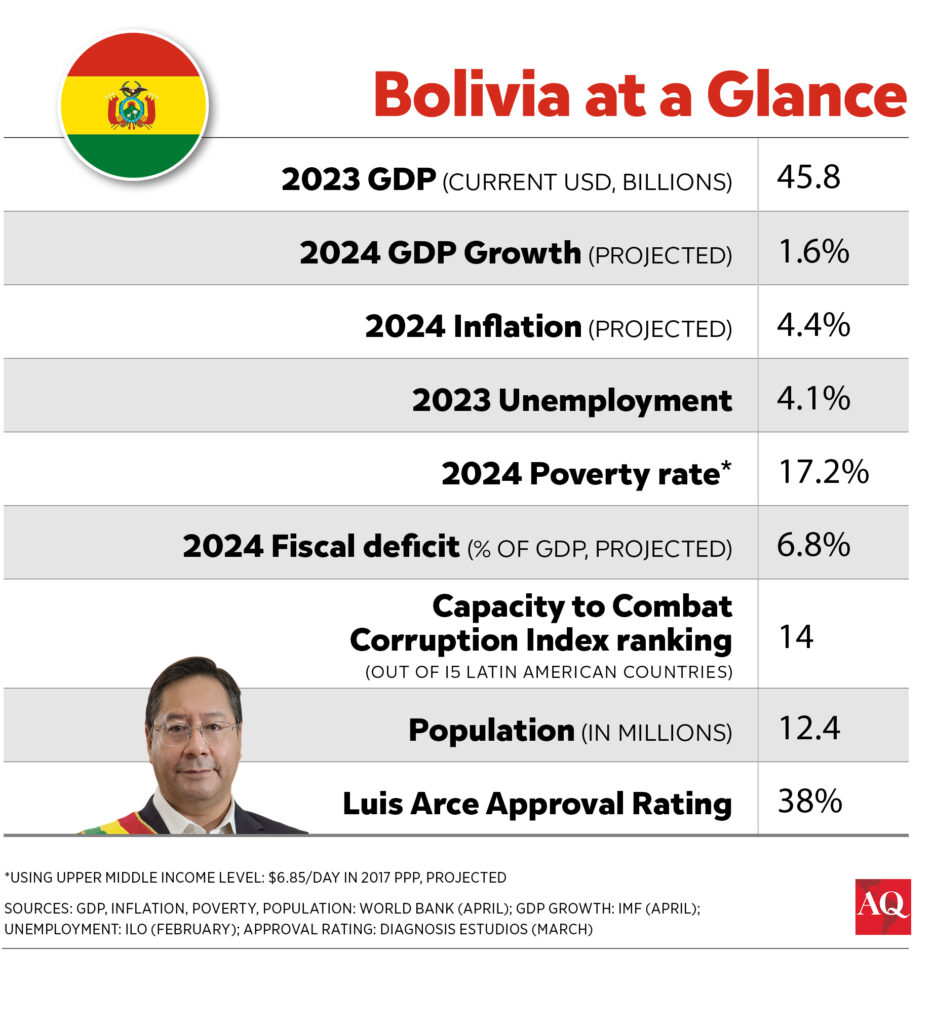

Arce, whose approval rating slipped to 38% in March according to Diagnosis Estudios, is focused on two things: the faltering economy and his political wrangling, said Gustavo Pedraza, a political analyst and former vice-presidential candidate of Carlos Mesa with the center-left Comunidad Ciudadana coalition party. Of the two battles, “the political fight is going to be more difficult,” he said. “Arce is going to have serious governability problems.”

Even so, he said, the opposition stands little chance of mounting a serious challenge to the MAS in 2025, as it’s divided into a constellation of parties that largely lack broad grassroots support.

Though the MAS’s legislative majority and the country’s largest grassroots organizations are fractured between evistas—loyal to Morales—and arcistas, the courts seem to have given Arce the advantage. The Constitutional Court ruled in December that presidents could not serve more than two terms, seemingly leaving Morales ineligible to run in 2025. In May, a high court forced the Supreme Elections Tribunal to recognize an Arce-aligned MAS party congress. These rulings have given Arce’s wing apparent control of the party apparatus—but they have also stirred outrage because new high court justices should have been selected by popular vote by last October. The Assembly prevented this from happening by dragging its feet for almost a year as the two wings of the MAS jockeyed for advantage; it finally passed the necessary legislation on February 6, after two weeks of intense evista protests.

All this has raised concerns that fragile institutions are being politicized and losing independence. “This MAS infighting is being felt in the Assembly, in the streets, in grassroots movements, and of course it’s affecting institutions,” Erika Brockmann, a political analyst and former social democrat senator, told AQ. “The judicial system is being instrumentalized … and now the electoral authorities are being subjected to its rulings,” she said. The outcome of the judicial elections later this year will be a crucial indicator of the judiciary’s independence, with high stakes for transparency efforts and the rule of law.

A teetering economy

Arce’s chances in his battle with Evo are likely to hinge on the economy, Zegada told AQ. The good news for him is that “Bolivians really expect stability more than growth,” she said, so if he can avoid calamity, he’ll be in good shape. “The economic situation can be put off, and the government can take palliative measures,” Zegada added. In extremis, allies Russia and China could also step in as lenders of last resort, Pedraza told AQ.

Still, the MAS conflict is limiting the government’s ability to prevent additional economic pain. The International Monetary Fund projects just 1.6% economic growth in 2024—partly due to the risk of a meltdown caused by the dollar shortage, which the Economist Intelligence Unit recently deemed “very high.” The nation’s central bank ended last year with just $1.7 billion in reserves—down from a peak of $15.5 billion in 2014—mainly because natural gas production cratered. This has raised doubts about whether the country can maintain the fuel subsidies and social programs that have kept poverty and inflation low or honor its international debt. The country owes $110 million in interest payments in both 2024 and 2025 on its 2028 and 2030 maturing bonds. While Fitch expects that the authorities will prioritize their scarce U.S. dollar liquidity, it acknowledged that “risks to debt service capacity are rising.”

Recent moves—including a modest yet historic deal with the private sector to boost exports and new zinc and biodiesel processing facilities—may improve Bolivia’s outlook next year. Arce also pledged to get gas production back on track by investing more in exploration and joint ventures with partners like Petrobras. This is a positive sign, said BMI/Fitch Solutions Senior Oil & Gas Analyst Dominika Rzechorzek, though she still projects a decline in production in 2024 of 1.2% after 2023’s 14% plunge.

Lithium on the back burner

Arce has also managed to procure over $600 million in multilateral loans—including $325 million for rural electrification from the World Bank and IDB; $62 million for cable cars in La Paz from the IDB; $100 million for pandemic recovery from JICA, the Japanese development agency; and $90 million for a highway from CAF, the Latin America Development Bank—but their approval is languishing in the divided Assembly.

So is a law that would allow Chinese and Russian lithium companies to rapidly expand their operations after they struck new deals with the Arce administration in recent months. Lithium development may be the simplest long-term way out of the economic doldrums, but the MAS conflict is holding up relevant legislation, and it’s low on Arce’s list of priorities because it wouldn’t bear much fruit until after the election, said Diego Von Vacano, a professor of political science at Texas A&M University who advised the Arce government on economic matters from 2019-22.

“Long-term, I think the lithium sector is the only real solution to the economic situation,” he told AQ. “But I see a closing off of information to minimize criticism … Arce should be developing a step-by-step plan, but he hasn’t because of these political concerns.”