Listen to a conversation with the author on the Americas Quarterly Podcast

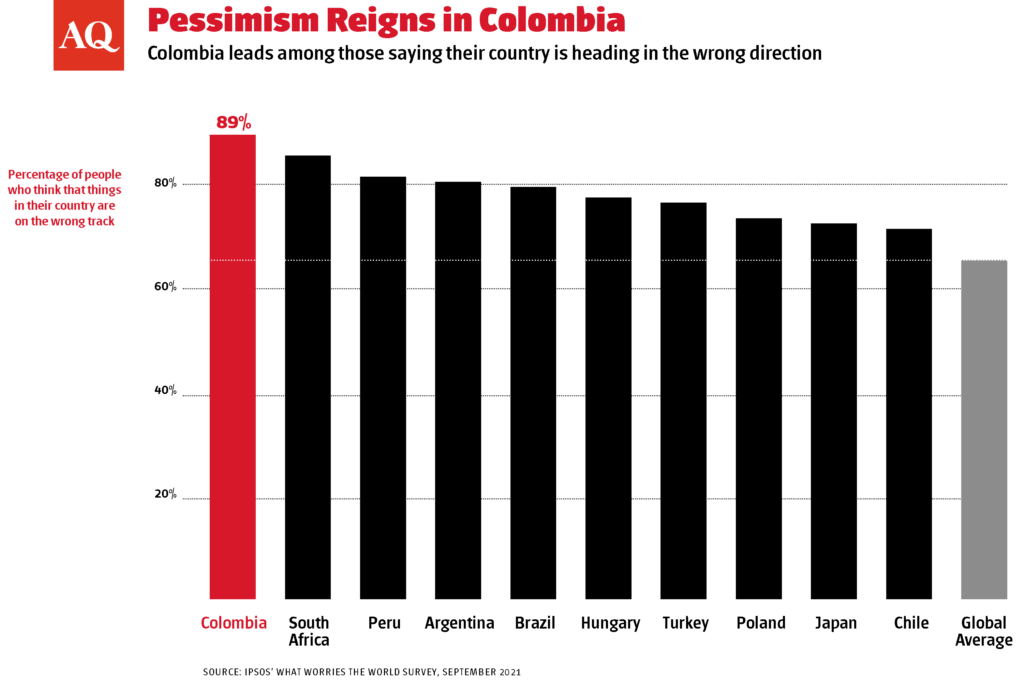

BOGOTÁ – With campaigns set to begin in earnest for Colombia’s elections for Congress and president, in March and May respectively, the atmosphere here is one of profound, perhaps unrivaled pessimism. A September poll by Ipsos showed that 89% of Colombians believed our country was “on the wrong track,” the highest percentage among 28 countries surveyed, and well above the 65% global average.

That, in itself, is concerning. The COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the feeling that Colombia is on the road to ruin; that the problems, instead of being solved, are only getting worse. Crime and corruption occupy most of the news. The current economic crisis has exacerbated tensions: 42.5% of Colombians are living below the national poverty line of approximately $90 per month (15.1% live in extreme poverty). Crime figures are up, and 96% of Colombians now believe the security situation is worsening, the highest percentage on record. Venezuelan migrants are becoming a political issue: Just in Bogotá, 15% of police detentions are Venezuelan migrants, even though they represent just 4% of the city’s population. The army is now patrolling Colombia’s major cities, as the police – weakened after the social explosion that took thousands to the streets last May – have been overwhelmed by crime.

On the corruption side, a $300 million contract made during the pandemic to provide internet to 7,000 rural schools had to be cancelled and is now the subject of a major scandal for the diversion of funds. According to the pollster Invamer, the president’s approval is in the low 20s, a historical low. The country is disoriented.

History teaches us that it is at times like this that societies easily fall into the hands of caudillos. Amid the grief and mistrust, the only political options that seem viable are those that propose a clean slate. Resetting the system and starting from zero, or at least kicking the table, seems to be the winning formula. Too often, this leap into the void turns into a spiral of bad decisions that can lead a country down a dark path with long-lasting consequences.

So how can we move forward in such a context? How to avoid an agenda that is only negative? I believe that we must find the courage and strength to talk about our own successes as a nation. Yes, this is difficult – talk of progress during tough times can make people roll their eyes (or worse), and make the messenger appear tone-deaf. But we’ve seen in other parts of the world what can happen when no one is willing to defend hard-earned progress, especially when it has come after decades of failures. This is not about getting intoxicated by false complacency or downplaying the serious problems we face. Instead, it is to recognize that overcoming failure brings confidence, which is necessary to build something new instead of just tearing things down.

In a new book, Cómo Avanza Colombia or “How Colombia progresses,” I try to highlight some positive examples from recent years. One of them is infrastructure, where our country turned from one of the worst global performers into what is the largest program of toll roads in Latin America, in terms of miles under construction and capital expenditures invested. And the results are already apparent: Up until 2014, Colombia had only managed to build 11 bridges across the Magdalena River, which essentially divides our country in half. Ten more have been built since then. This means that in seven years, we did more than in previous centuries.

Becoming a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2018 is another story of success. A number of individually small steps were required in the seven-year long process. Although this is not likely not to divide Colombia’s history in two, all the changes introduced are improving the way the public sector operates.

Colombia is now a leader in the emerging world in terms of early childhood care. This is the result of a well-planned – and well-funded —strategy to bring children under five to the CDIs (Centros de Desarrollo Infantil), which are landmarks in every town, where kids benefit from access to world-class specialized attention.

The list is long. Changes to reduce payroll taxes – to generate more formal employment– and increased taxes on tobacco, alcohol, sugary drinks – to reduce their consumption and improve health – are part of the story. The same applies to carbon taxes, which were introduced in 2016, one of the earliest adoptions in the emerging world. Another strength that was especially valuable during the pandemic is that the entire Colombian population has basic health insurance, something that many countries would like to emulate. Two-thirds of the population do not pay a cent for this insurance. The country has much better outcomes in international sports competitions. None of this happened by mere luck.

Each episode of progress has its own dynamics and leaves lessons. However, the relevant question is what is behind these positive experiences. What are the common elements that policymakers and others, including members of civil society, can learn from and apply to solving the current challenges? I believe they all share five elements:

1. Learn from your own failures and from the successful experiences of others.

2. Develop a plan with a clear roadmap.

3. Once you have that, prioritize. Political capital depreciates fast and must be invested smartly and selectively.

4. Dedicate time and resources to building institutions, ahead of cutting ribbons.

5. Very little is obtained on the first try, so don’t give up if things do turn as expected. Persist and persist.

Politics matters more than good ideas, but it is good ideas that bring progress. We must not lose our voice, and forget to talk to our fellow citizens about what we can achieve when we combine purpose and leadership. This is the time to remind everyone that choosing good ideas over demagoguery is always the right thing to do.

—

Cárdenas is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and was Colombia’s finance minister from 2012 to 2018. Follow him on Twitter @MauricioCard.